System Programming

这篇文章展示了系统编程的学习记录

System Programming

0 Background

0.0 What is Operating System?

An operating system is an intermediary between a computer user and the hardware

Make the hardware convenient to use

Manages system resources

Use the hardware in an efficient manner

0.1 Types of Operating Systems

-

Batch

- Single CPU

- User submits large number of tasks at one time

- OS decides what to run and when

- Back-to-back single tasking

-

Time Sharing

- Multiple users connected to a single CPU

- Many user terminals

- Multiple tasks run simultaneously using time-sharing, giving users the feeling of having multiple dedicated CPUs running in parallel

-

Parallel

- Multiple CPUs closely coupled to form one computer

- Higher throughput and better fault tolerance

- Each CPU can be running batch tasking or time-sharing multitasking

-

Distributed

- Multiple CPUs loosed coupled via networking

-

Real-time

- Very strict response time requirements

- Periodical tasks, every job of a task has a strict deadline

0.2 Single Tasking System vs. Multi-tasking System

- Single Tasking System Each task, once started, executes to its very end without any interruption from other task(s).

Simple to implement: sequential boundaries between tasks, and resource accesses. Few security risks Poor utilization of the CPU and other resources

Example: MS-DOS

- Multi-tasking System

Very complex

Serious security issues

How to protect one task from another, which shares

the same block of memory

Much higher utilization of system resources Support interactive user/physical-world interface

Example: Unix, Windows NT

0.3 Hardware Basics

OS and hardware closely tied together Basic hardware resources:CPU, Memory, Disk, I/O

0.3.1 CPU

-

CPU controls everything in the system

It is involved in any work needs to be done -

Most precious resource

This is what you are paying for

Users would usually prefer high utilization (from useful work) -

Only one process running on a CPU at a time

-

Millions or even billions of machine instructions per second

Getting faster all the time

0.3.2 Memory

- Limited capacity

Never enough, and expanding over the years - Temporary (volatile) storage

- Electronic storage

Fast, random access - Any process to run on the CPU must first be loaded into memory

0.3.3 I/O

- Many I/O devices

Keyboard, mouse, monitor, printer etc. - Most I/O devices are painfully slow

- Need to find ways to deal with high I/O latency

Like multiprogramming

0.4 Protection and Security

- OS must protect itself from users

Reserved memory only accessible by OS - OS may protect users from one another

0.5 Interrupts

Modern OSs are event driven

Event is signaled by special hardware signal sent to the CPU

Two types of events Hardware Interrupts: caused by external hardware, can occur at anytime Software Interrupts (aka Exceptions, Traps): caused by software, synchronous to CPU clock

0.5.1 Interrupt Philosophy

Use an interrupt table and special hardware to redirect CPU execution

By the end of interrupt handling, the CPU can resume the interrupted process

0.5.2 Interrupt Table

Large array of addresses indicating what code to run (interrupt routine) for a given interrupt

Each interrupt has a corresponding number associated with it On Intel processors this is from 0 to 255 This gives fixed size interrupt table

Use the interrupt number to index into the array to find out what code to run (interrupt routine)

0.5.3 Hardware to Support Hardware Interrupts

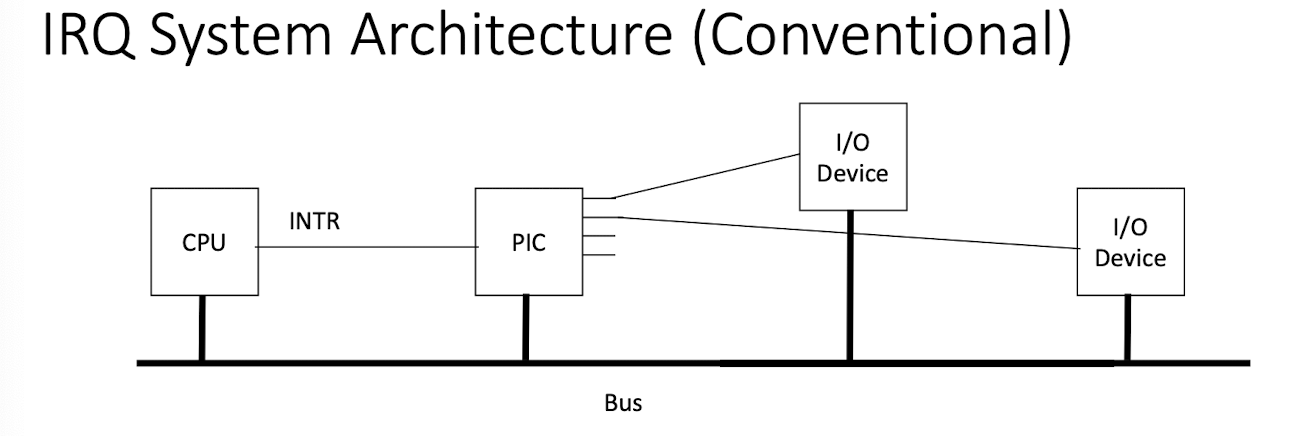

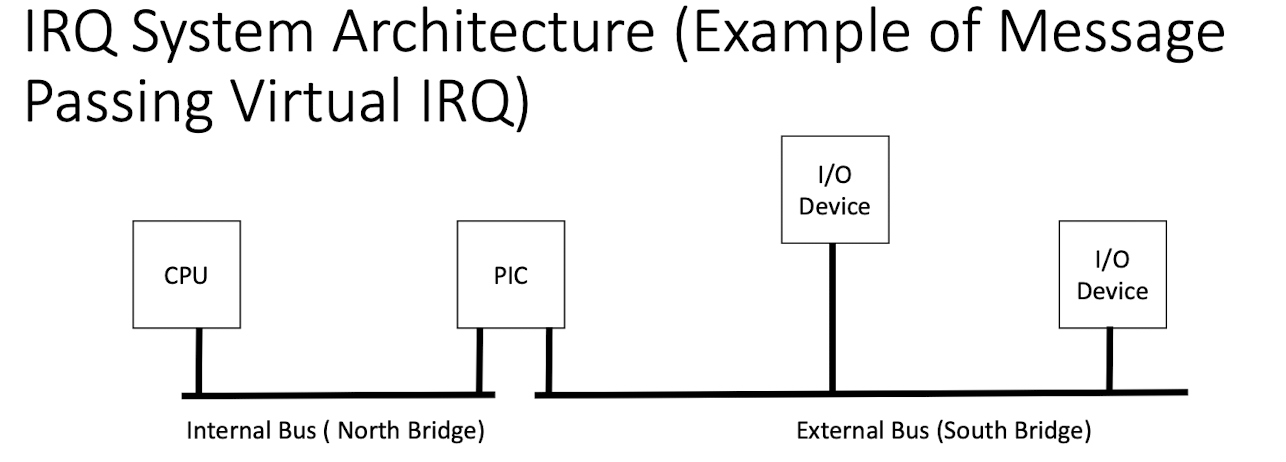

Programmable Interrupt Controller (PIC) Connected to I/O devices via Interrupt Request Lines (IRQ) or Bus (e.g. PCI Express)

PIC connected to the CPU by a special line or bus

CPU<==>PIC<==>I/O devices

<==> can be special signals via dedicated wire lines (IRQ), or special sequences of back-and-forth messages via bus(es) (virtual IRQ)

0.5.4 IRQ Architecture

0.5.5 Hardware Handling of Interrupts (Conventional IRQ as an Example)

After each instruction executes, CPU checks if the IRQ pin voltage has been raised If so

1. Sets the system into kernel mode (if not already there)

2. Determine interrupt number (from PIC or instruction)

3. Read appropriate interrupt table entry

Special register contains base address of interrupt table

Each entry in table is fixed size so easy to calculate where to

look in memory (e.g. memloc = iptr + 8 * intNum)

4. Saves the process state to the stack (particularly, the program counter)

5. Saves error code to stack (if it exists)

6. Loads the program counter with the value stored in the interrupt table

This starts the CPU executing in the interrupt routine

0.6 Peripheral Devices

Input Devices

Output Devices

Storage (memory is usually not considered as a peripheral)

0.6.1 Peripheral Devices for Embedded Systems

Embedded Systems: computer systems that do not look like conventional computer systems, e.g. mobile devices, devices tightly coupled with the physical world (i.e. cyber-physical systems).

Input Devices: Sensors

Output Devices: Actuators

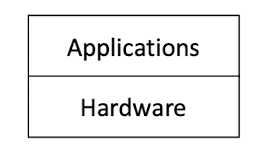

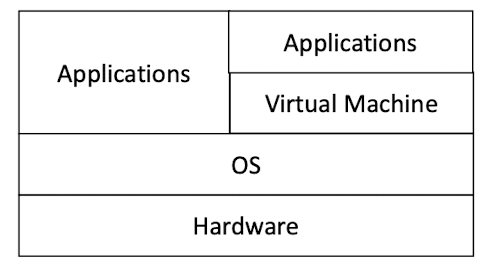

0.7 Historical Perspective

- Application built on top of hardware

Problems: Complexity: have to know the tedious low-level programming details of the hardware Inflexibility: when the hardware changes, the application has to change with it.

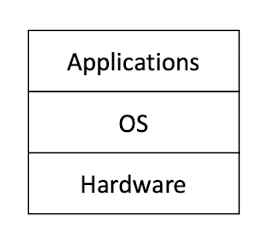

- Application built on top of OS

Ideal: OS application programming interface (API) hides the complexity and heterogeneity of hardware programming. As long as the OS API remain the same, the hardware can change. Design goal conflict: Full exploitation of hardware features Versus Full platform independence and simple API

- Application built on top of OS

Ideal: OS application programming interface (API) hides the complexity and heterogeneity of hardware programming. As long as the OS API remain the same, the hardware can change. Design goal conflict: Full exploitation of hardware features Versus Full platform independence and simple API

Want to exploit more features of the hardware: Application + OS Want to be more platform independent and simpler API: Application + Virtual Machine (VM)

Virtual Machine (VM) can hide the heterogeneity of OS APIs

As long as the VM API remain the same, the OS (and hardware) can change, and the application can remain the same.

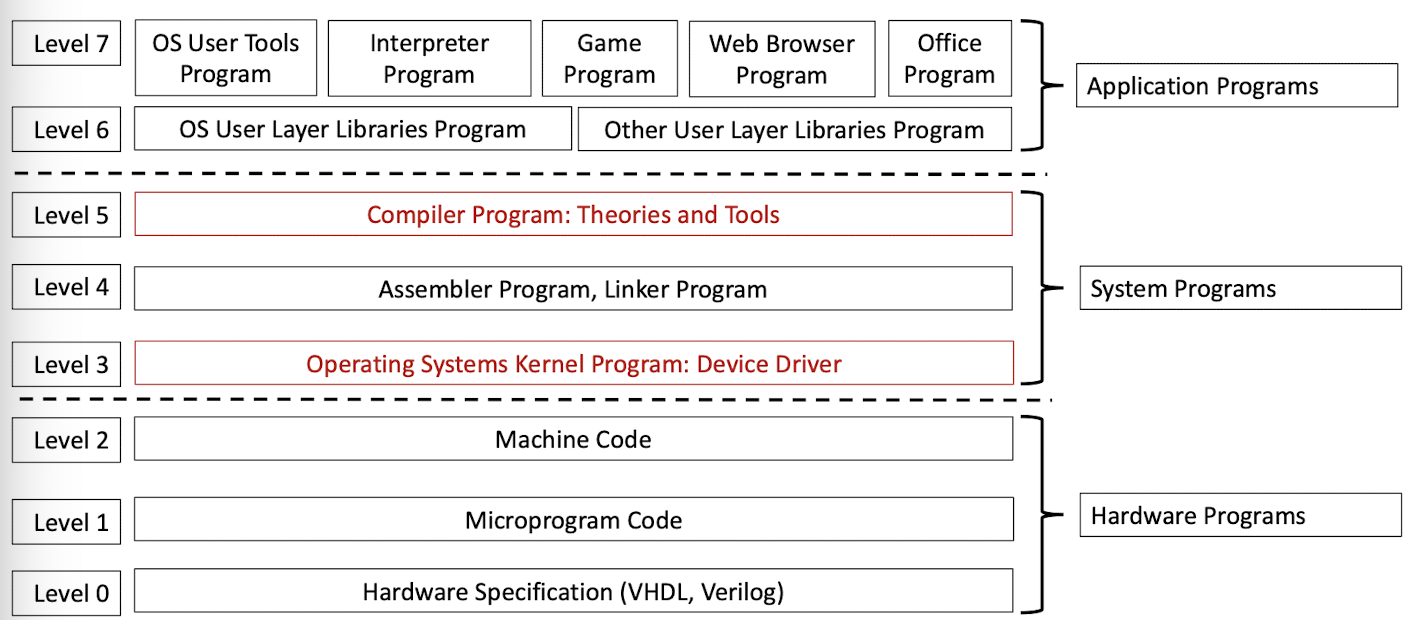

What is System Programming?

- Application programs (+ application layer libraries)

- Programs for direct interaction with users

- Compiler programs, assembler programs, linker programs

- Tools that convert application programs to executables

- Operating systems kernel programs

- Programs that interface other software with the hardware

Layers of Programs (Development Time)

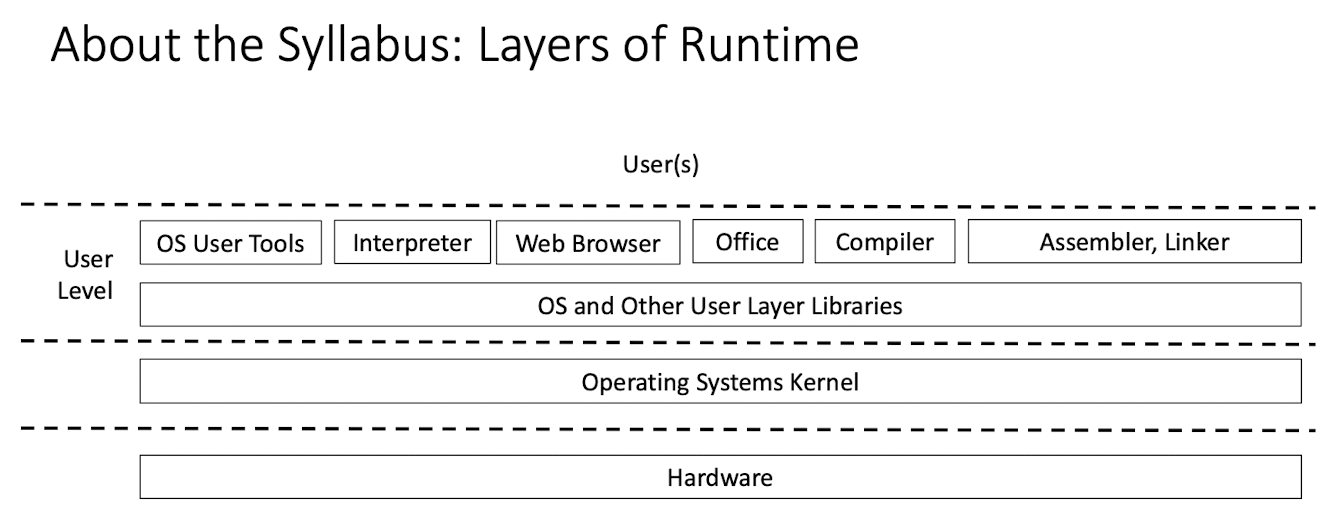

Layers of Programs (Run Time)

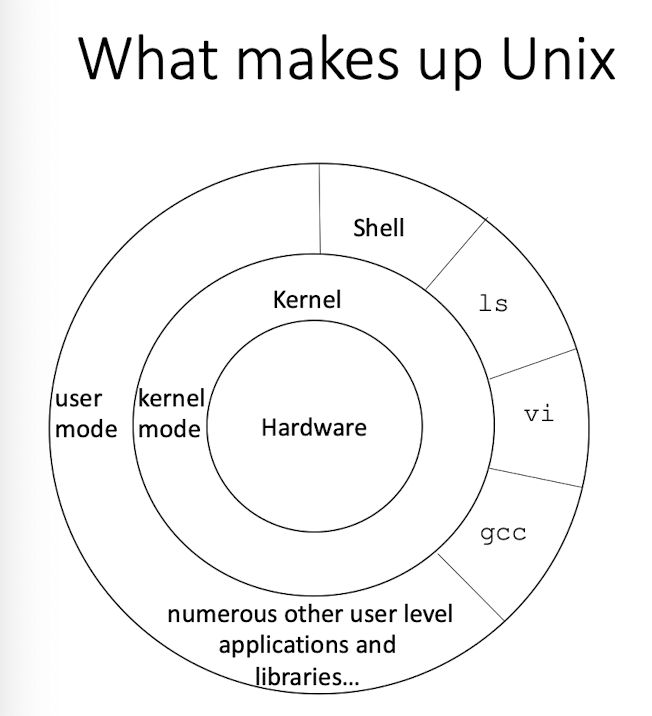

1 Unix

1.1 The Unix Philosophy

- Modular design

- A collection of simple tools, with limited well-defined functions

- File system

- Inter-process communication

- The tools can be easily composed (via

>,>>,<,|,``) by a shell to accomplish complex tasks

1.2 Unix Kernel and System Calls

Main duties

- process scheduling and management

- inter-process communication

- memory management

- file management

- network stack management

- date and time management

- system accounting

- security

- device management

- interrupt and exception handling

Other parts of the Unix system, as well as user programs, request the kernel for various services through system calls

A system call is an entry point into the kernel, typically packaged as a function call, as part of the OS API.

- a software interrupt (trap) switches the CPU hardware to the kernel mode

- execute kernel routines

- return kernel mode first, to the scheduler, check schedule of other tasks

- switches back(via scheduling*) to the user mode to resume the user application

1.3 Unix Commands and Utilities

- A large set of tools for various basic user level functions

- A vocabulary and a grammar, to combine basic user level functions to nearly arbitrary sophisticated functions

- Not part of the kernel, but a part of the OS

- Typically accessed via the Shell

1.4 Unix Shell

- A powerful command interpreter (a user level application) for Unix – accepts user text commands and carries them out

- Can combine various user level applications to serve more sophisticated functionalities

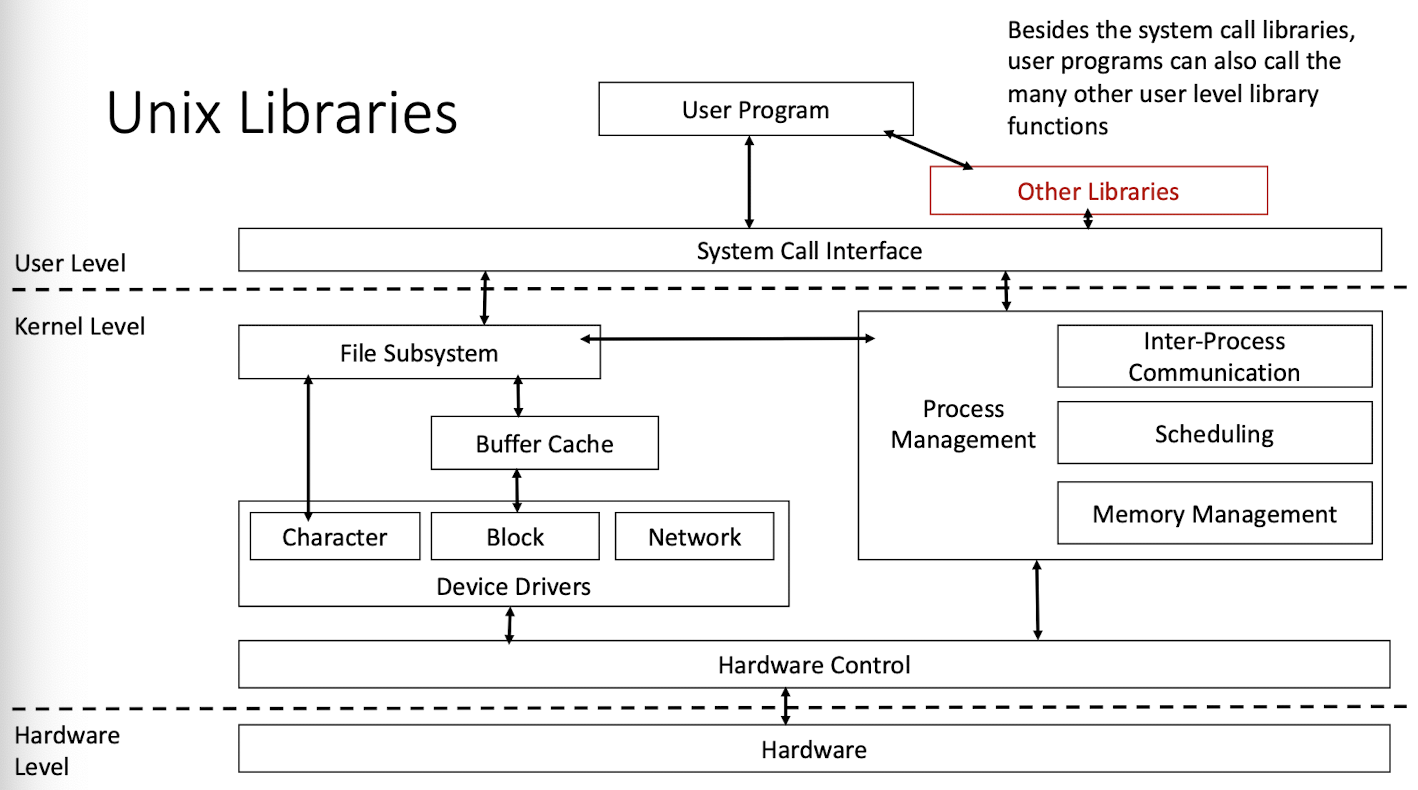

1.5 Unix Libraries & Device Drivers

Features of Unix

- Portability

- Multi-user Operation

- Multitask Processing

- Hierarchical File System

- Powerful Shell

- Pipes

- Networking

- Robustness

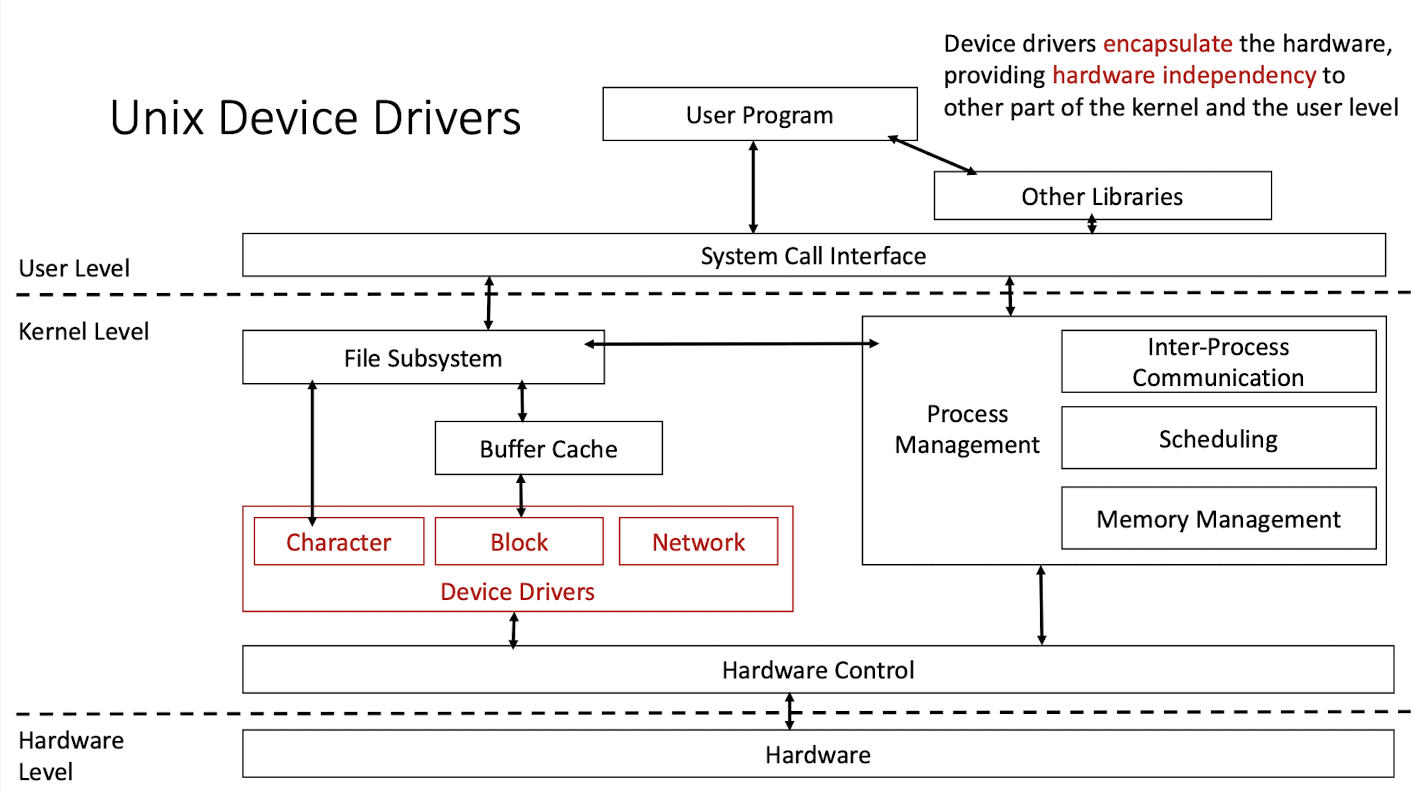

1.6 Unix is Portable

-

Unix is a relatively hardware independent OS. Various mechanisms (device driver, various C program interfaces inside of the kernel and to the user level) are designed to encapsulate the hardware specifics, facilitating porting between hardware platforms.

-

One key to the portability is the device drivers, specific modules that encapsulate the hardware details from the other parts of the kernel and the user level.

1.7 Unix supports multi-users and multi-tasking

- For a single user, time sharing can still support multi-tasking. Multiple users may run multiple tasks concurrently.

- Unix supports background processing, which allows a user to initiate a task “in the background” and then proceed to other activities. Unix time shares between the front-end commands and background jobs.

- Unix allows the creation of new tasks from an existing task.

1.8 Unix has a hierarchical file system

- Unix files are organized into separate directories.

- Directories are themselves organized into a tree-like structure. There is one master directory, the so-called root directory, from which various sub-directories branch off.

- The hierarchical structure offers a maximum flexibility for grouping information in a way that reflects its natural structure.

- A single user’s data may be grouped by activity

- Data from many different users can be grouped according to corporate organization

- As a result, stored data is easier to locate and manage

1.9 Unix shell is powerful

T he Unix shell supports a number of convenient features, such as:

Redirection of application input and output, e.g.

ls > myfiles

The ability to manipulate groups of files with a single command.

Executing a sequence of commands stored in a text file, called a “shell script,” allowing us to build our own commands, which may be parameterized.

Being used as a programming language that provides string-valued variables and control flow primitives including branching and iteration

1.10 Unix’s pipe is novel

A pipe passes the standard output of one command directly to another command, to be used as its standard input, e.g.

who | sort

Allows any number of commands to be connected in a sequence, and automatically handles the data flow from one program to the next

who | sort | lp

Produces the same effect as if one large program, rather than several small ones, had been executed.

- Allowing the combination of several simple programs to perform more complex functions

- Eliminating the need for new software development.

1.11 Unix supports networking

Supports TCP/IP protocols, and provides a new OS abstraction, the socket, that allows application-level programs to access the Internet.

The socket abstraction acts as an interface between application level programs and the underlying TCP/IP protocols.

1.12 Unix is robust

When encountered an error, a Unix program does not abort. Instead, the program receives a returned value indicating an error condition, and it is up to the program to check for the error and handle it.

Typically, a returned error value is negative if the return type is int, or a NULL if the return type is a pointer.

You can call the C library function perror() to output a message string to the standard error file, to further explain the error.

Unix Demo

Task 2:

-

ls: list the files in the current directoryls -l: list the files in the current directory in long formatls -a: list the files in the current directory, including the hidden filesls -t: list the files in the current directory, sorted by timels -lat: list the files in the current directory, including the hidden files, in long format, sorted by time

-

cd: change the current directory.: the current directory..: the parent directory

-

cp: copy a filecp file1 file2: copy file1 to file2cp file1 file2 file3 dir: copy file1, file2, file3 to dircp -r dir1 dir2: copy dir1(all the content) to dir2 recursively

-

mv: move a filemv file1 file2: move file1 to file2mv file1 file2 file3 dir: move file1, file2, file3 to dirmv dir1 dir2: rename dir1 to dir2

-

rm: remove a filerm -rf dir: remove dir recursively and forcefully

-

mkdir: make a directorymkdir dir: make a directory nameddir

-

who: show the users who are currently logged inwhami: show the current userwho -q: show the number of users who are currently logged inwho -u: show the idle time of the users who are currently logged in

-

cat: concatenate files and print on the standard outputcat file: print the content of file on the standard outputcat file1 file2: print the content of file1 and file2 on the standard outputcat file1 file2 > file3: concatenate file1 and file2, and write the result to file3cat file1 file2 >> file3: concatenate file1 and file2, and append the result to file3

-

man: an interface to the on-line reference manualsman command: show the manual of commandman -k keyword: search the manual for keywordman -f command: show the manual of commandman -a command: show all the manual of command

-

gcc: GNU project C and C++ compilergcc file: compile filegcc file -o file: compile file and output the executable file to filegcc file1 file2 -o file: compile file1 and file2 and output the executable file to file

Task 3:

-

vi: a text editorvi file: open file in vii: enter insert modeesc: exit insert mode, enter command mode

-

Under command mode:

:w: save the file:q: quit vi:wq: save and quit vi:q!: quit vi without savingh: move leftward;l: move rightward;j: move downward;k: move upwardw: move rightward word by word;b: move leftward word by worddw: delete the word after the cursoru: undo the last commanddd: delete the current line$: move to the end of the line;^: move to the beginning of the line

-

gedit: a text editorgedit file: open file in gedit

Task 4: Shell output redirection

who > users: redirect the output ofwhoto fileusers, overwriting(replace) the original content ofuserswho >> users: append the output ofwhoto fileusers

Task 5: Shell input redirection

wc < users: redirect the content ofuserstowc, and count the number of lines, words, and characters inuserswc -l: count the number of lineswc -l < output.txt > output1.txt: count the number of lines inoutput.txt, and write the result tooutput1.txt

Task 6: write, compile, and run a C program

vim hello.c: write a C program in vigcc hello.c -o hello: compile the C program and output the executable file tohello./hello: run the executable file

External Task: pipeline - make a pipe among processes

ls -l | wc -l: count the number of files in the current directoryls -l | grep "hello": list the files in the current directory whose name contains “hello”ls -l | grep "hello" | wc -l: count the number of files in the current directory whose name contains “hello”

2 Unix Processes

- What is a process?

- What does a process look like in the system?

- When is a process created? By whom?

- How is a process created? In how many ways?

- When does a process stop? Can we wait for a process to die?

- What is a process called if it never die?

2.1 Common definition

A process is an instance of a program in execution (the execution of the program has started but has not yet terminated).

Process is dynamic while program is static.

A process is the basic unit for competing the resources. In particular, it is the basic active entity to CPU scheduler.

2.2 How to understand it?

State of a computer at clock tick (i.e. discrete time) $i$: $S(i)$ = (register 1’s value, register 2’s value, …, 1st memory byte’s value, 2nd memory byte’s value, …, 1st hard disk byte’s value, 2nd hard disk byte’s value, …, peripheral 1’s register 1’s value, peripheral 1’s register 2’s value, …).

State of an execution $e$ at clock tick $i$: $s(e, i)$ = (resources used by $e$ at $i$, state of the resources used by $e$ at $i$).

A process is the time sequence of ${s(e, i)}$, where every two consecutive states $s(e, j)$ and $s(e, j+1)$ have causal relationship determined by the program logic and the OS.

2.3 how to turn a program into a process?

The program is read into memory.

A unique process ID is assigned. OS kernel creates a process structure instance to record information related to this process.

Necessary resources to run the program are allocated.

The initial state $s(e,0)$ is set, which will trigger its next state $s(e, 1)$, which will trigger its next state $s(e,2)$, … determined by the program logic and the OS.

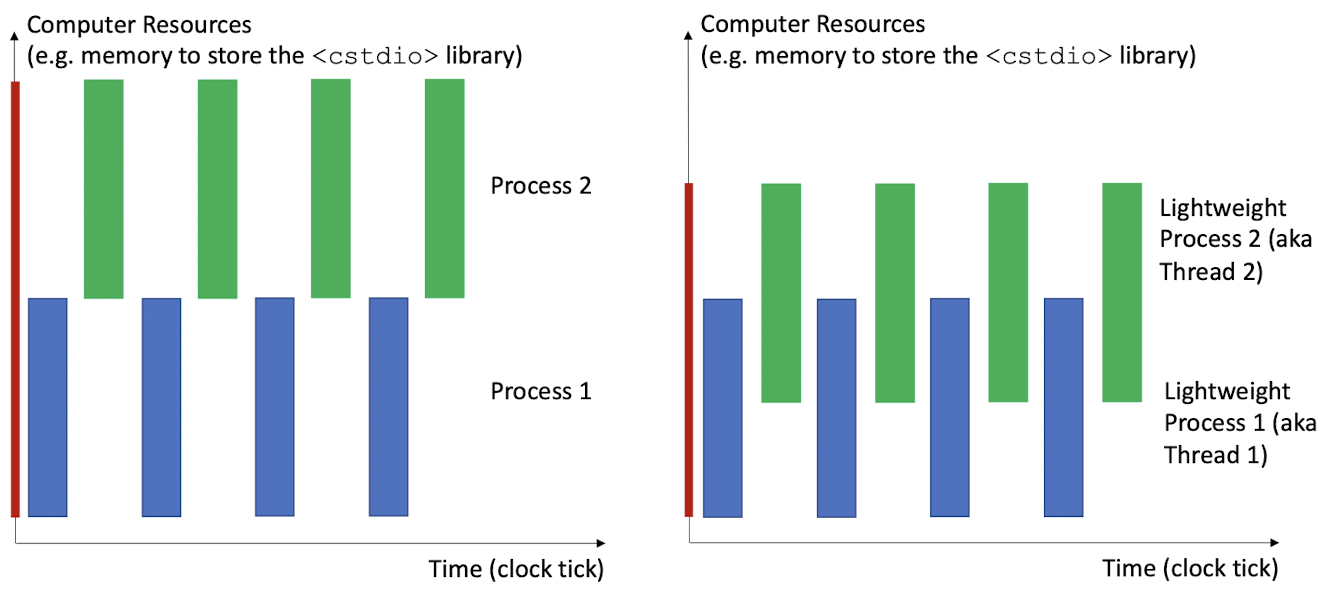

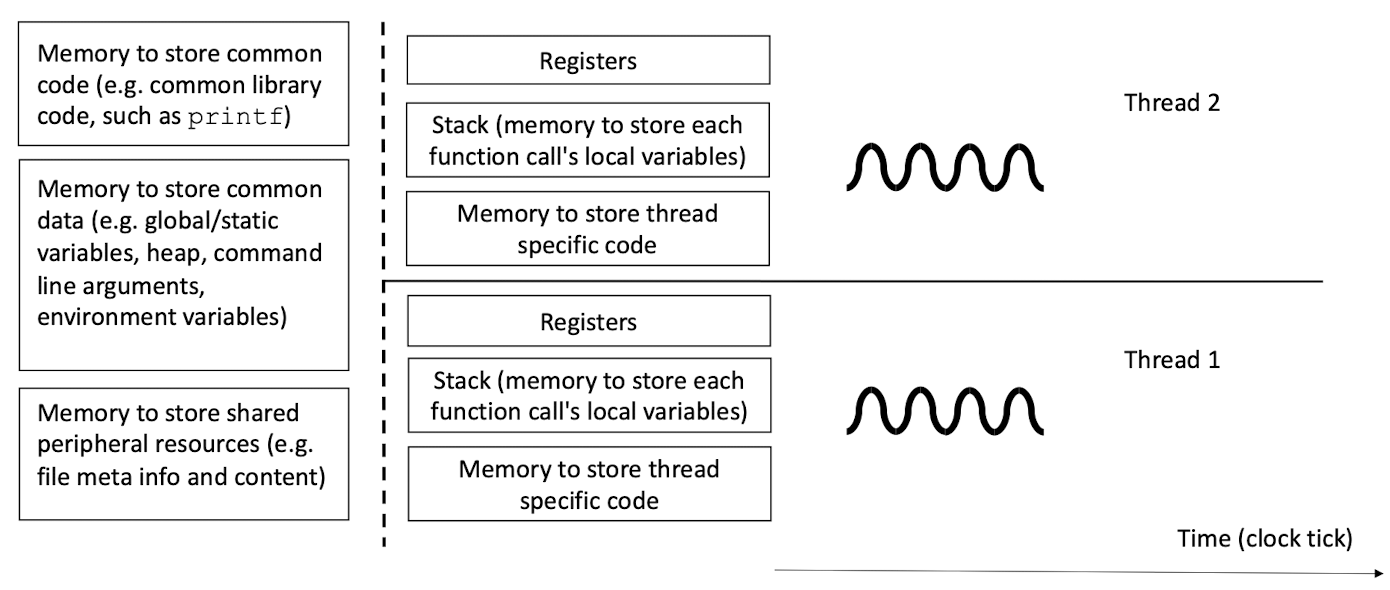

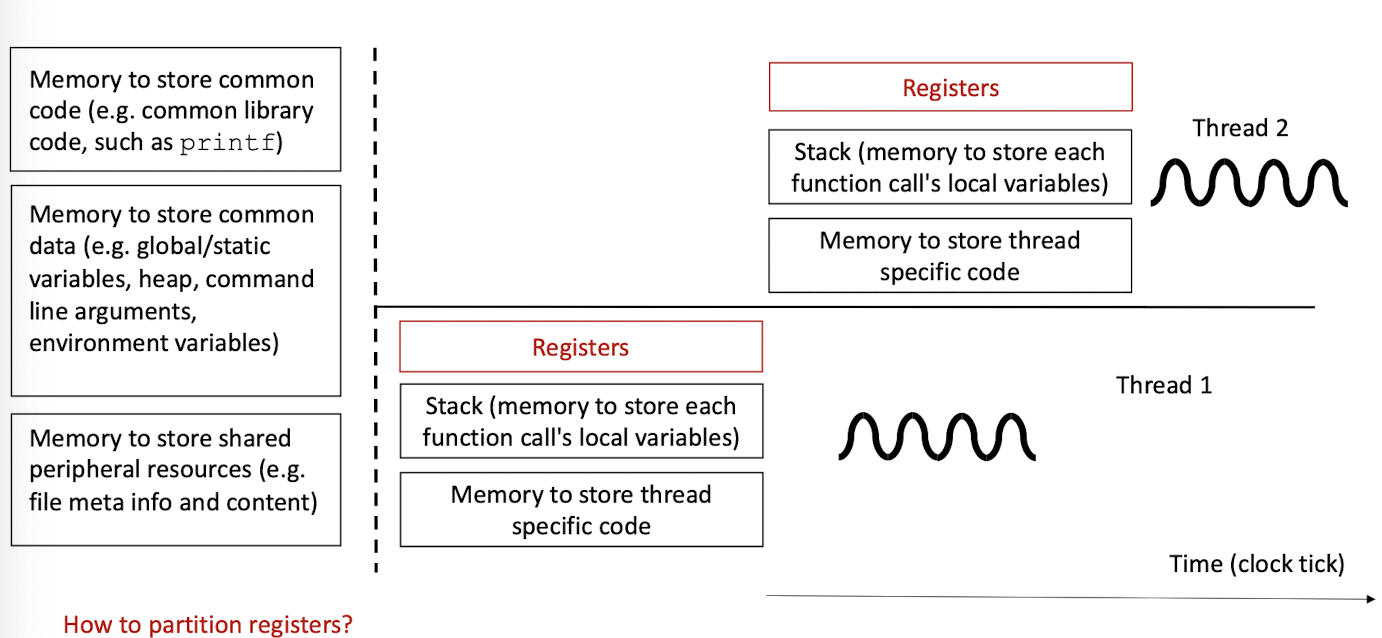

2.4 Notion of threads (lightweight processes)

A process is the time sequence of ${s(e, i)}$, where every two consecutive states $s(e, j)$ and $s(e, j+1)$ have causal relationship determined by the program logic and the OS.

In older OSs, each process has its exclusive set of resources, even for processes that are related (e.g. sharing data). This is wasteful.

Modern OSs propose the notion of “threads”. Threads are processes that have shared resources, typically created by a same ancestor process. Because the resource allocation is more thrifty, threads are also called “lightweight processes”.

- left: multi-processes -

fork() - right: multi-threads

2.5 What resources to share and what not to share?

- store and restore the register values

- partition the registers into different sets temporarily for threads

2.6 Thread realization and programming interface

And at the user level, there is a de facto standard C thread programming interface: PThread (POSIX Thread).

But different OSs (even OSs belonging to the Unix family) have different ways to realize the concepts and the PThread programming interface.

For example, modern Linux no longer differentiate threads and processes, all are realized as copy-on-write (COW) processes (aka “task”). For example, every time the parent thread creates a new thread, in the Linux implementation, there is a parent COW process creating a child COW process.

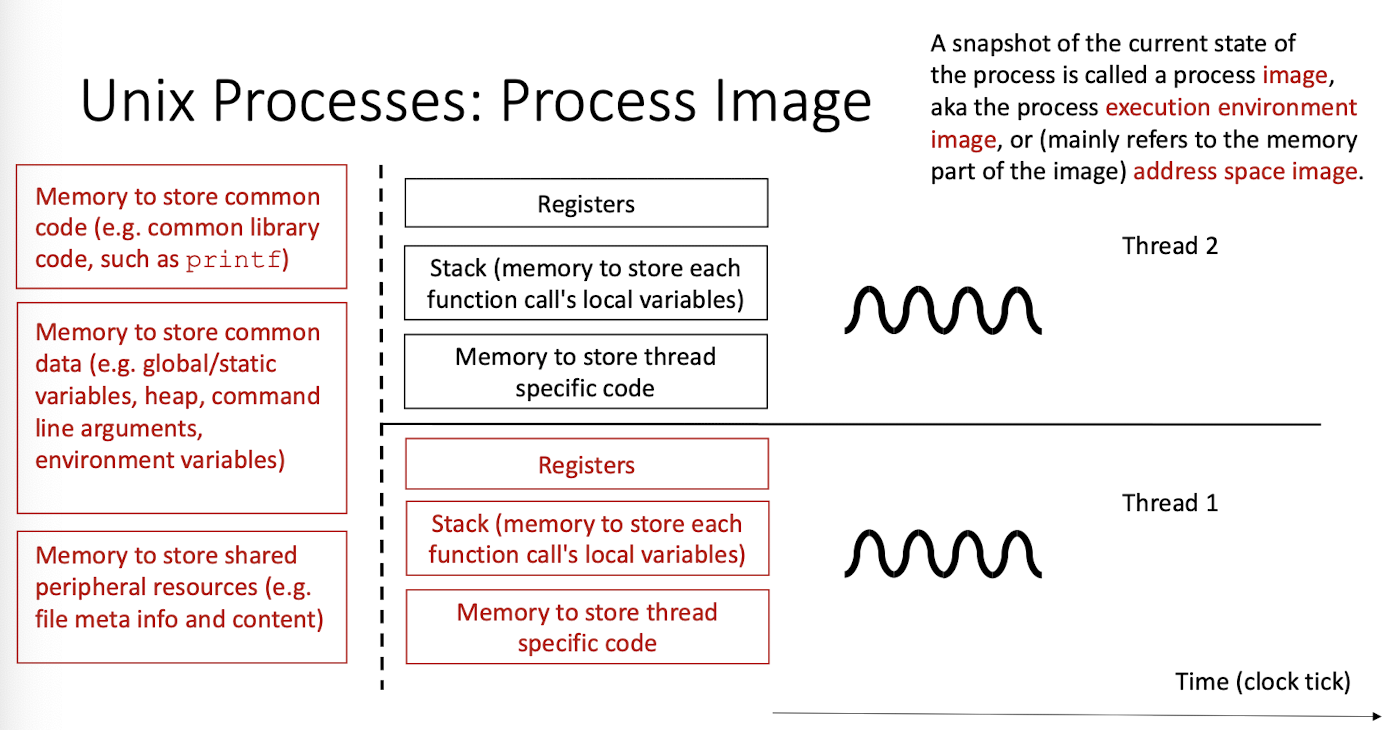

2.8 Process Image

2.9 Process management

Besides its image, a process has its corresponding meta data (in kernel) for the OS to manage it, e.g. process ID.

A Unix OS typically maintains a hierarchy of processes related by parent-child links: the process that requests to create another process is called the parent process, the created process is called the child process.

A child process inherits all the properties of its parent when it is created, but can change after creation (even changing its code image).

- Process ID – integer PID

- Parent process ID – an integer PPID

- User process ID – an integer UID

- In Unix, each user has a unique user ID.

- Each process is associated with a particular user called the owner of the process, which executes the program.

- The owner has certain privileges with respect to the process.

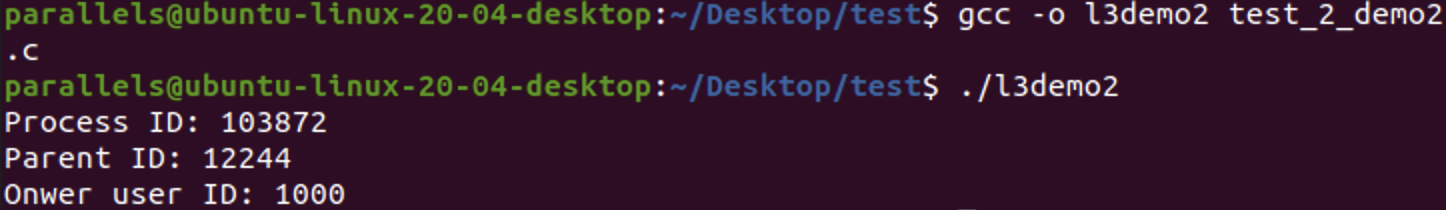

Use getpid, getppid, and getuid to determine the ID of the current, parent, and the owner.

psis the short for “process status”.pslists your current processesps –alists more processes, including ones being run by other users and at other terminals (but not include the shells)ps –lprints longer, more information lines, including UID, PID, PPID, process status, etc.

2.10 Related Portable OS Interface (POSIX) APIs

The Portable Operating System Interface (POSIX) is a family of standards specified by the IEEE Computer Society for maintaining compatibility between OSs.

Demo Task 2

getpid: get the process ID of the current processgetppid: get the process ID of the parent processgetuid: get the user ID of the current process

|

|

Result

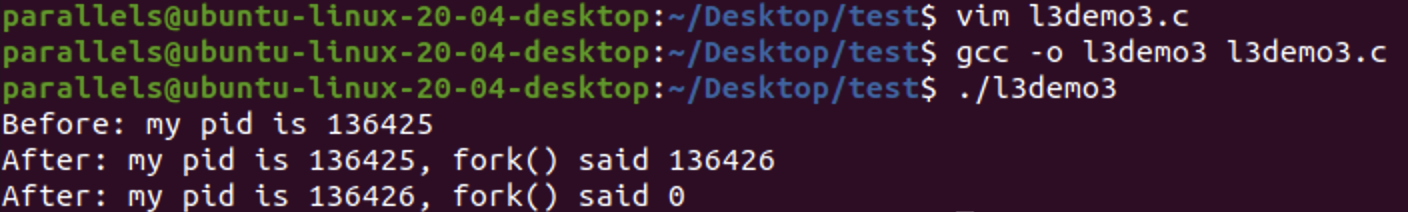

Demo Task3

fork(): create a new process- Allocates a new chunk of memory and kernel data structure.

- Copies the parent process’s image and kernel data structure into the new process’s, with needed modifications (e.g.PID, PPID).

- Adds the new process to the set of “Ready” processes.

- Returns control back to both processes (by setting the program counter in the respective image, and leaving the processes to the scheduler).

- Return twice: once in the parent, once in the child.

|

|

Result

- use

man -S3 sleepto see the manual ofsleepsystem call - user

man sleepto check sleep user command - orphan process may happen since the parent process may terminate before the child process of the above code

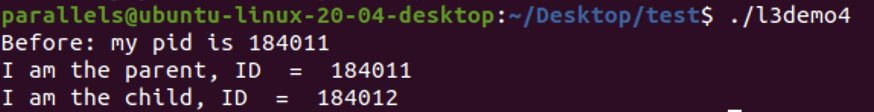

Demo Task 4

|

|

Result

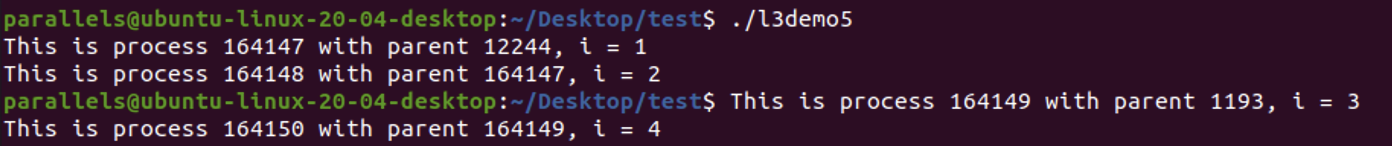

Demo Task 5

In-class exercise: forking a chain of processes

- the child process will fork a child process, then previous child process will die; the new child process will fork a child process, then previous child process will die; …

|

|

Result

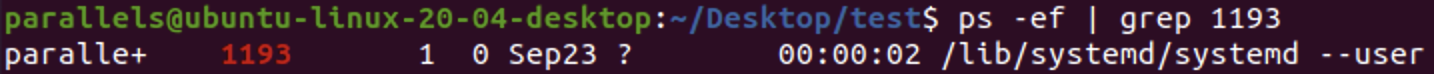

parallels@ubuntu-linux-20-04-desktop:~/Desktop/text$- the result above shows the parent process

PID=164147has terminated before the child processPID=164149are created, so these two child processes become orphan processes, with parent processPID=1193(theinitprocess - user) - For thr first

fork(), the parent process will break out of the loop, and callfprintf(), then terminate. This parent process has the “full image” of whole c program. So when this process terminates, the whole c program terminates, and terminal will returnparallels@ubuntu-linux-20-04-desktop:~/Desktop/text$

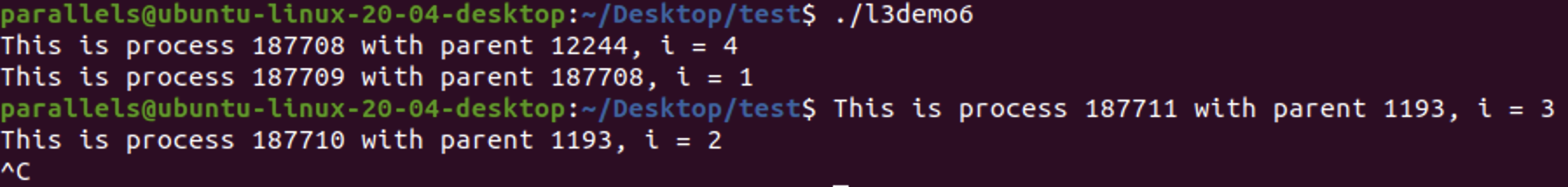

Demo Task 6

- In -class exercise: forking a fan of processes

|

|

Result

- the order can be different since the parent and child processes are running concurrently which is scheduled by scheduler

- the parent process of

PID=187708isPID=12244(thebashprocess) - the result above shows the parent process

PID=187709has terminated before the child processPID=187710are created, so this child processes become orphan process, with parent processPID=1193(theinitprocess - user)

The fork system call creates a copy of the calling process. However, many application requires that the child process execute a different program from the parent process.

The exec family of system calls provides a facility for overlaying the calling process with a new executable module

execloads a new executable and arguments into the process image, and calls the main(…) function.- If successful,

execnever returns; the calling process is completely overlaid by the new program and is started from its beginning. - The traditional way to use the

fork-execcombination is to have the child execute the new program while the parent continues to execute the original code.

2.10.1 wait() system call

After fork, both parent and child proceed independently. If a parent wants to wait until the child finishes, it executes wait or waitpid system call:

pid_t wait(int *stat);- In general, the

waitsystem call causes the caller process to pause until a child terminates or stops, or until the caller receives a signal. - The call returns right away if the process has no children or if a child has already terminated or stopped but has not yet been waited for.

- The

statis a pointer to an integer variable that stores the exit status of the child.

- In general, the

If wait returns because a child terminated, the return value is positive and is the PID of that child

Otherwise, wait returns –1 and set errno.

errno == ECHILDindicates that there were no unwaited-for child processes;errno == EINTRindicates that the call was interrupted by a signal;

Three states of wait()

- no return

- -1

- child process ID

2.10.2 Orphan processes

If a parent process terminates first without waiting for its children, the children processes become orphan processes.

It is almost always poor programming practice to create orphaned processes, because there may be no indication to the user there are still processes running. If one of the ==orphaned processes== gets into an ==infinite loop==, the user may be completely unaware of it; and the orphaned process may continue execution even after the user has logged out.

Demo Task 7

- In -class demo: wait() example with process chain

- Only one forked process is a child of the original process.

|

|

One of results

|

|

2.10.3 exec

The fork system call creates a copy of the calling process. But many applications require the child process to execute code different from the parent’s.

The exec family of system calls provides a facility for overlaying the calling process with a new executable module

exec loads a new executable and arguments into the process image, and calls the main(…) function.

If successful, exec never returns; the calling process is completely overlaid by the new program and is started from its beginning.

The traditional way to use the fork-exec combination is to have the child execute the new program while the parent continues to execute the original code.

Demo Task 8

- In-class demo:

execexample on creating a process to runls -l

|

|

Compare with typing

ls -ldirectly in terminal, the process performsls -lin./l3demo8is the grandson of the terminal process, and the process performsls -lin./l3demo8is the child of the terminal process.

Demo Task 9

- In -class demo:

execexample on creating a process to runls -lexecvp():p- search the executable file in thePATHenvironment variablev- arguments are passed to main as an array of char *const pointers, each pointing to a C string.

|

|

2.10.4 Variations of exec

|

|

path : C string (a NULL ended array of char) representing the full path of the executable file

file : C string representing only the file name of the executable file, the path is searched from the PATH environment

arg0 : should be the same as file name, the 0th argument passed to main.

... : a list of char const * pointers, each points to a C string, as arguments passed to main; the list must end with a NULL.

argv : an array of char const * pointers, each points to a C string, as arguments passed to main.

envp : an array of char const *, each points to a C string of format “environment_variable_name=value”.

l: arguments are passed to main as a list of char const * pointers, each pointing to a C string; the list must end with a NULL.

v: arguments are passed to main as an array of char const * pointers, each pointing to a C string.

e: an array of environment variable “environment_variable_name=value” pairs are explicitly and entirely passed to the new process image.

p: use the PATH environment to search for the executable file.

An opened file descriptor remains open in the new process image, unless was fcntled with FD_CLOEXEC or opened with O_CLOEXEC. This is how stdin, stdout, and stderr are opened for the child process.

Demo Task 10

- In-class demo:

exechas no return.

|

|

|

|

|

|

exec will not create a new process, still the same process. The memory will be re-written by the new image.

|

|

|

|

e: entire

2.11 Process termination

Upon termination of a process, the OS de-allocates the resources held by the process, updates the appropriate statistics, and notifies other processes, specifically these include:

- cancel pending timers and signals;

- release virtual memory spaces;

- release locks, closing open files;

- notifying the parent in response to a wait system call.

What happens if the parent is not currently executing a wait()?

The child process’s kernel management meta info (e.g. task struct) will remain there, though the child process image is gone. The child process hence becomes a zombie.

A normal termination occurs if there was

- A

returnfrommain, - An implicit

returnfrommain, - A call to the C function

exit, or - A call to the

_exitsystem call

exit calls user-defined exit handlers and may provide additional cleanup before it invokes the _exit system call.

exit takes a single, integer argument, called exit status, which will be made available to the parent process (which may be waiting). By convention, a zero means success, some non-zero value means something has gone wrong.

2.11.1 Abnormal process termination

A process can terminate abnormally by

- calling

abort, causing theSIGABRTsignal to be sent to the calling process, or - processing a signal that causes termination.

A code dump may be produced.

User-installed exit handlers will not be called upon abnormal termination.

2.12 Background processes

Recall that the shell is a command interpreter which

- Prompts for commands.

- Reads the commands from standard input, forks children to execute the commands, and waits for the children to finish.

- A user can terminate execution of a command by

ctrl-c.

Most shells interpret a command line ending with & as one that should be executed by a background process

When a shell creates a background process, it does not wait for the process to complete before issuing a prompt and accepting additional commands.

Cannot send ctrl-c to a background process via the command input.

2.13 Daemons

A daemon is a background process that normally runs indefinitely (have an infinite loop).

Unix relies on many daemon processes to perform routine tasks

pageoutdaemon handling paging,in.rlogindhandling remote login requests,- The web server daemon receiving http connection requests

- ftp daemon, mail daemon, … etc.

Demo Task 11

|

|

umask

umask(0): set the file mode creation mask(umask) to 0, so that the file mode of the daemon output file is not restricted.umask()sets the calling process’s file mode creation mask tomask & 0777,7means111in binaryopen()andmkdir()mkdir(): the mode of the created directory is (mode & ~umask & 0777)modeis default mode- e.g.

umask(0)->mkdir()->0777 & ~0 & 0777->0777: the deafult mode will be remained

setsid

- although

setsidwill move to another session, but the opened file is still be accessed - the child process calls

setsid()to create a new session and obtain a new session ID (SID). If setsid() fails (returns -1), the program exits with a failure status. - The child process then changes the current working directory to the root directory using

chdir("."). If thechdir()call fails, the program exits with a failure status. - child process closes the standard input, standard output, and standard error file descriptors. This is done to disconnect the daemon process from the terminal, as it no longer needs them.

above code is a daemon process, which is terminal-realted not login-related.

3 Unix File System

What is a file in Unix? How many types of files? How are the files in a file system structured? How is a file represented in memory and disk? How to find the file using its name? How to access files from a Unix program?

3.1 Unix File System

File system provides abstractions of naming, storage, and access of files. A file is a container of some information: data, program. In Unix, devices (disks, tapes, CD ROMs, screens, keyboards, printers, mice, etc.) are also treated as files, so as to provide a unified and device independent interface to applications.

3.2 How to handel devices?

- system calls to the programmer for performing control and I/O to devices.

- handled by device drivers, which hide the details of device operation and protect the devices from unauthorized use.

In Unix, disk files and other devices are named and accessed in the same way as data files.

- Unix provides a uniform device interface (called file descriptors).

- Allow uniform access to most devices through file system calls –

open,close,read,write, etc.

3.3 Types of files in Unix

- Regular file: an ordinary data file on disk – contains bytes of data organized into a linear array;

- Special file: a file representing a device – located in the /

devdirectory- Block special file: devices transferring info in blocks or chunks, just like disks, CD ROM

- Character special file: devices transferring info in stream of bytes that must be accessed sequentially, just like keyboards, mice, printers, etc.

- Directories: provided to allow names (not physical locations) of files to be used.

- User gives a file name and Unix makes a translation to the location of the physical file-done via directories

3.4 Difference between regular and directory file

- Contents: data vs file info

- Operations: what can be done and who can do them, the access right

3.5 ls -l command

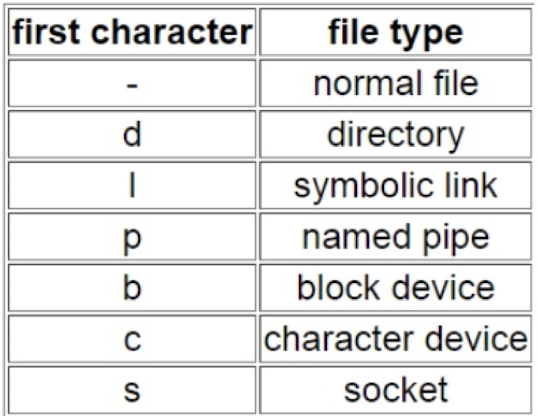

For each file there are ten characters before the user and group owner. The first character shows the types of file

access right

Demo Task 1

What are the differences between a regular file and a device file?

|

|

- content will be displayed on the terminal for

ttydevice file

3.6 Hierarchical file organization

A Unix file system has a hierarchical tree structure where internal nodes are directories and leaf nodes are files

- fully-quallified path name uniquely specifies a file:

/dirA/dirB/My1.dat. - relative pathname, begining from the current directory rather the root ditrectory:

../My2.dat

3.7 Current working directory

At anytime, every process has an associated directory called the current working directory (cwd)

- Denoted by a dot

., e.g.,mv ../file1 . - The cwd associated with a user’s login shell is called the user’s home directory.

pwdprints the name ofcwd- A relative pathname always starts with the path to the cwd.

The C library function getcwd returns the pathname of the current working directory

char *getcwd(char *buf, size_t size)sizespecifies maximum length pathname. If longer than the maximum, returnsNULLand setserrono to ERANGE.

|

|

3.8 File representation

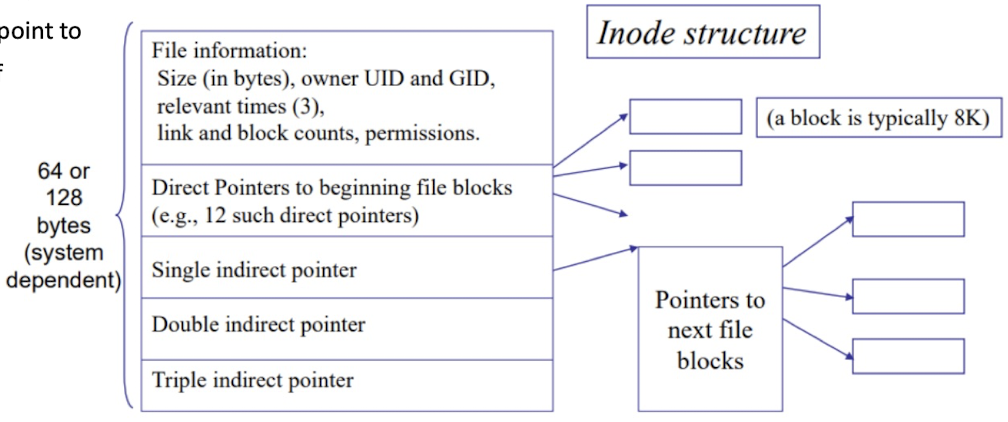

3.8.1 i-node

- Information about a filesystem structure is stored both on disk and main memory.

- Unix uses a logical structure called

i-nodeto store the information about a file on disk – each file in a file system is represented by an i-node:

- i-nodes are stored at the front of each region of disk that contains a Unix file system.

- both conceptual and physical

- A regular file has a number called the i-number, which is an index into an array of the i-nodes on disk, one-to-one mapping.

- Each i-node corresponds to a unique i-number (index).

- data blocks may be placed in neighboring disk blocks, but it can not be guaranteed.

- more layers(tree structures) to access the data blocks

- store pointers in data blocks

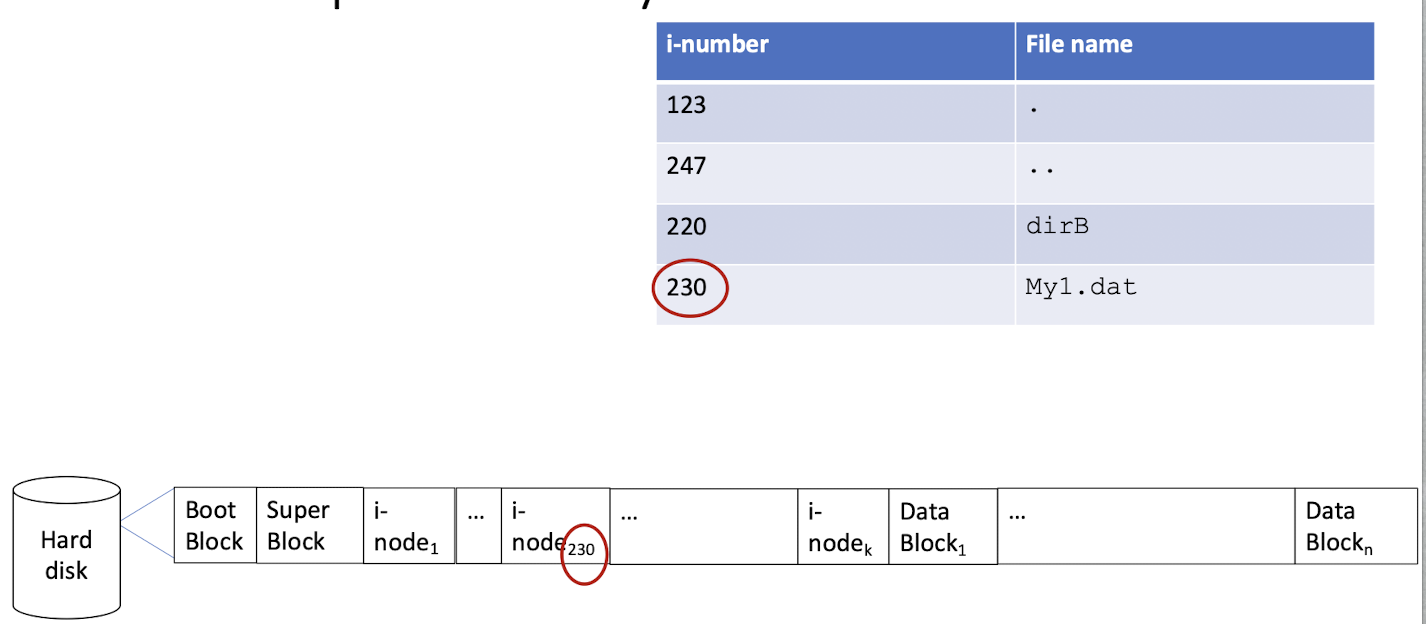

find the i-number of a file, by given the file name

- A directory contains a list of entries mapping file names to i-numbers (hence the i-node).

- A <name, i-node> pair is called a link. You can create many links for a file (multiple names).

- i-nodes are the hidden part, while directories are the visible structure of the Unix file system.

- Hence, the correspondence between a file name and its i-node is stored in the directory file.

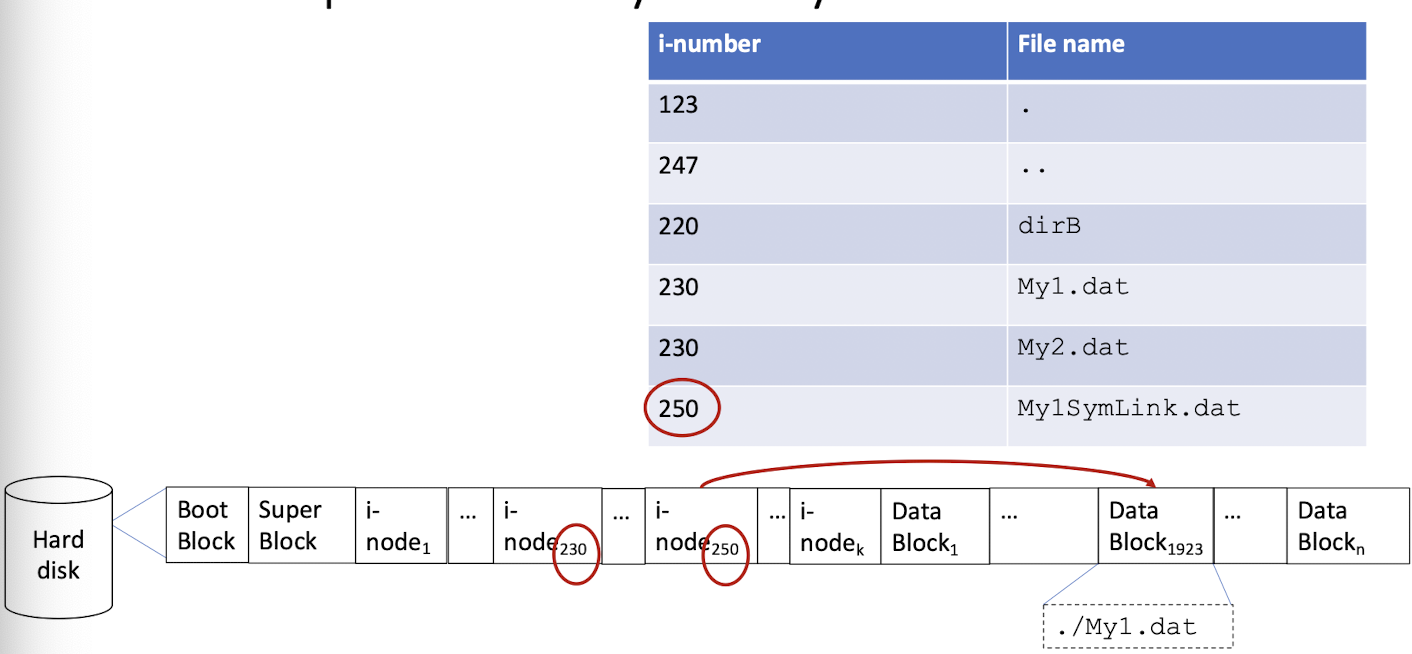

[Example of directory file]

3.8.2 Hard link & Symbolic link

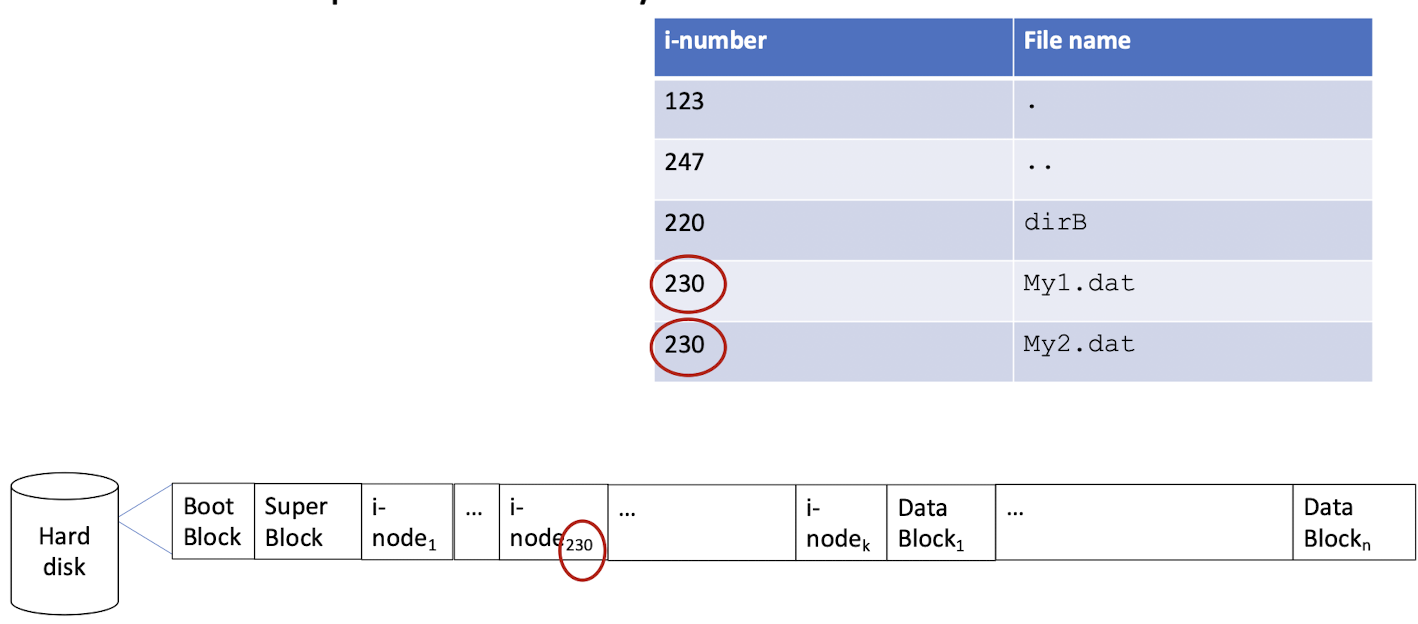

[Example of directory file: hard link]

Hard link creation command: ln My1.dat My2.dat

Hard link

- create a new entry for the same

i-node, when modifying any of entry, the result will change

[Example of directory file: symbolic link]

- create a new i-ndoe index

Symbolic link

- normal symbolic link: when the “root” is moved, the link will be broken

- absolute symbolic link: when the “root” is moved, the link will not be broken

- i-node reference a new data block which stores a URL, of which the reference of source file

absulute path or relative path

- Hard links must be on the same file system, while symbolic links can cross file systems.

- Hard linked files stay linked even if either one is moved; Symbolic linked files break if the original is moved.

Remove links

- deep remove and shallow remove

- deep - remove the entire file from disk

- shallow - remove the reference not the file itself

- reference counter(part of i-node in filr info.) from the memory perspective to check using deep remove or shallow remove

The key of links is checking whether the reference/path is valid or not.

3.8.4 File storage

- 12 direct pointer can point to $12 * 8KB = 96KB$ of file content.

- A single indirect pointer points to a block of direct pointers. A block can contain 8KB/4bytes = 2K pointers = 2048 pointers. 2048 direct pointers can point to $2048 x 8KB = 16MB$ of file content.

- A double indirect pointer points to 2048 single indirect pointers, that is $2048 * 16MB = 32GB$ of file content.

- Similarly, a triple indirect pointer points to $64TB$ of file content.

- So one I-node can at the most point to $64TB + 32GB + 16MB + 96KB$ of file content.

3.9 File Access

In C programs, a file is represented by a file pointer or file descriptors.

- provide logical names (handles) for performing device-independent I/O.

Unix file system calls use file descriptors (via open, read, write, close, and ioctl).

ANSI C I/O library uses file pointers (via fopen, fscanf, fprintf, fread, fwrite, fclose, etc.).

File descriptors - (in unistd.h)

- standard input:

STDIN_FILENO - standard output:

STDOUT_FILENO - standard error files:

STDERR_FILENO - Corresponding to constants

0,1,2in<unistd.h>

file pointers - (in stdio.h)

- standard input:

stdin - standard onput:

stdout - standard error files:

stderr

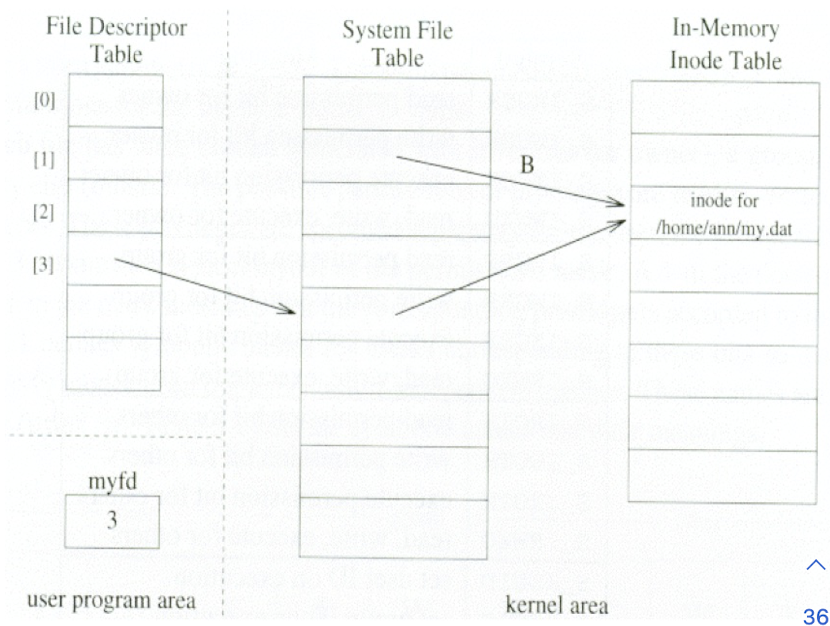

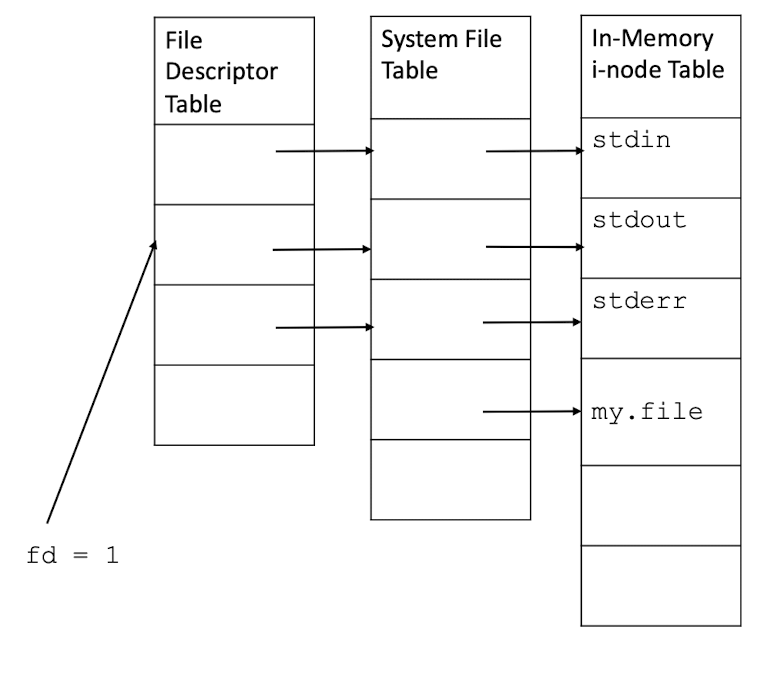

3.9.1 File Descriptor

low-level identifiers provided by the operating system to access files and I/O resources Process specialized

- System File Table(SFT) entry contains information about whether a file(within a process) is opened for

- read/write;

- permission;

- lock;

- read/write offset etc.

Several entries in SFT may point to the same physical file.

- When new files are opened, it is assigned the lowest available FD.

- Accessing files for I/O is a three-step process, whether it is a regular file or a device:

- Open the file for I/O

- Read and write to the file

- Close the file when finished with I/O

open a file

int open(const char* pathname, int flags)int open(const char* pathname, int flags, mode_t mode)

pathname: absolute or relative path name of the file to be openedflags: access mode -O_RDONLY,O_WRONLY,O_RDWRand bitwise-or’d(using|) with sero or more of the following flags:O_APPEND: the file is opened in append mode.O_CREAT: if the pathname does not exist, create the file as a regular file; must add the access permission mode parameter (e.g. 0644).- …

Return of open

- Returns the opened file’s file descriptor or

–1if an error occurred (theerrnois set accordingly)

read a file

bytes = read(fd, buffer, count)

- Read from file associated with

fd; placecountbytes intobufferfd: file descriptor to reasd frombuffer: pointer to any arraycount: number of bytes to read

- Returns number of bytes read or

-1if an error occured

Demo Task 3

|

|

write a file - overwrite

bytes = write(fd, buffer, count)

- Write contents of

bufferto the file associated withfd, writecountbytes into the fileO_TRUNC: if the file already exists and is a regular file and the access mode allows writing, truncate it to length 0.fd: file descriptor to write tobuffer: pointer to any arraycount: number of bytes to write

- Returns number of bytes written or

-1if an error occured

Demo Task 4

|

|

close a file

return_val = close(fd)

- Close an open file descriptor

- Returns

0if successful,-1if an error occured

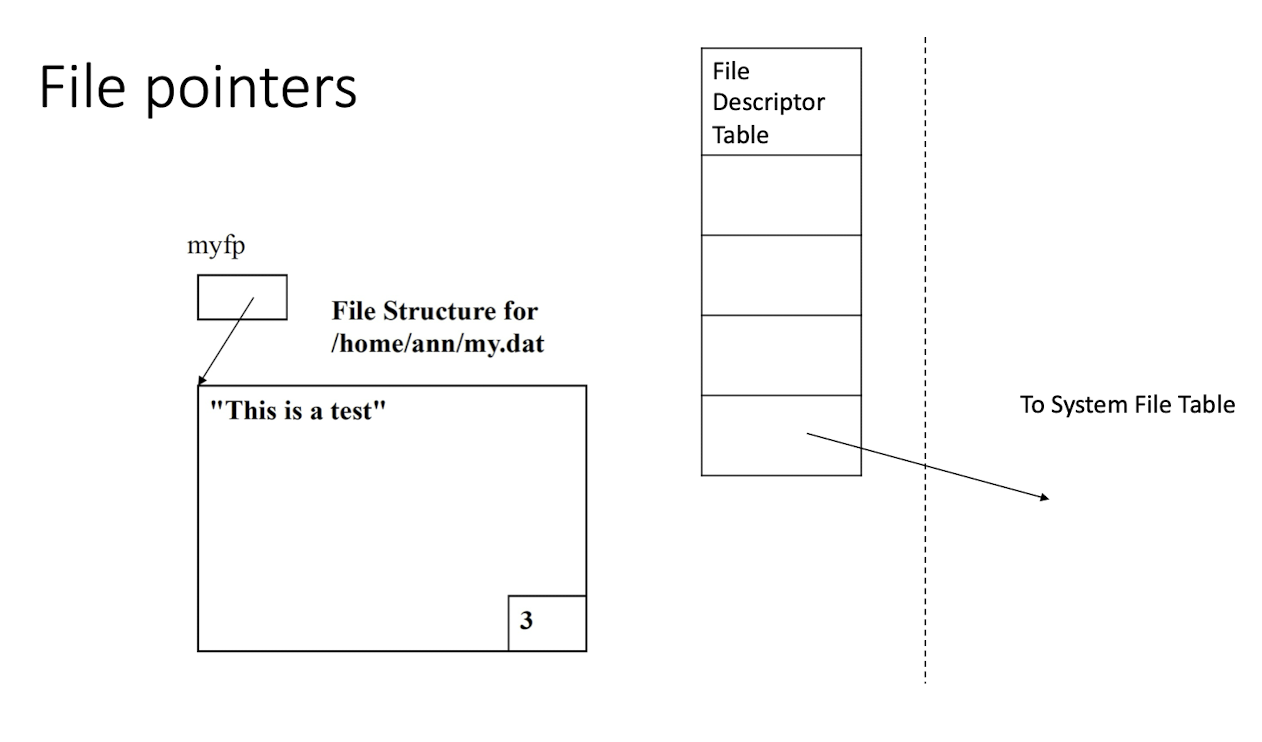

3.9.2 File Pointer

higher-level abstractions used by programming languages or libraries to manage the current position and perform high-level file operations.

- A file pointer points to a data structure

FILE, called a file structure in the user area of the process. - A file structure contains a buffer and a file descriptor (so a file pointer is a handle to a handle)

Demo Task 5

|

|

- overwrite

|

|

fopen() and fclose()

|

|

Path:char*, absolute or relative path Mode:r– open file for readingr+- open file for reading and writingw– overwrite file or create file for writingw+- open for reading and writing; overwrites filea– open file for appending (writing at end of file)a+- open file for appending and reading

|

|

- Closes the opened file represented by

file_stream

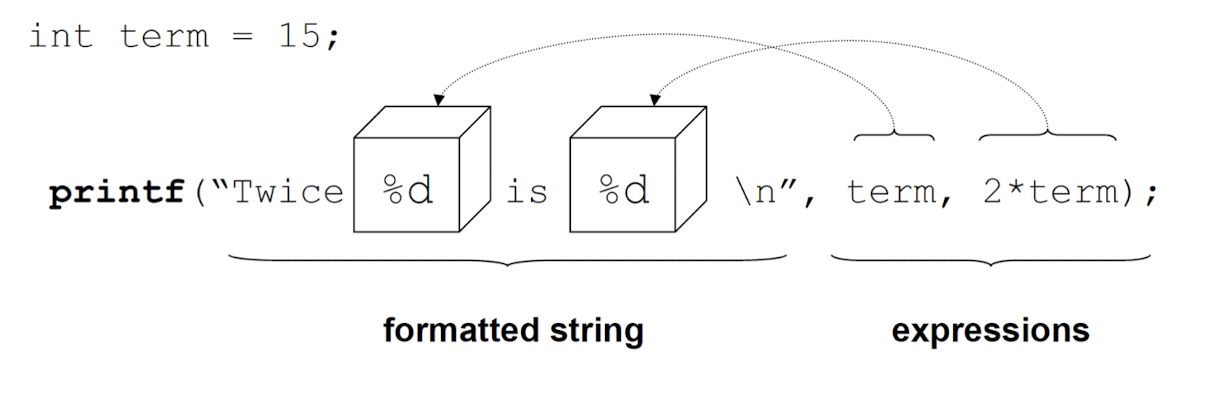

printf()

|

|

formatted_string: string that describes the output information, variable types are escaped with%- The formatted string is followed by as many expressions as are referenced in the formatted string

Escaping variable types

%d,%i– decimal integer%u– unsigned decimal integer%o– unsigned octal integer%x,%X– unsigned hexadecimal integer%c– character%s– string or character array%f– float%e,%E– double (scientific notation)%g,%G– double or float%%– outputs a%character

Demo Task 6

[Example]

|

|

|

|

|

|

scanf()

|

|

- Similar syntax as

printf, only the formatted string represents the data that you are reading in. - Must pass variables by reference

- e.g.

scanf(" %d %c %s", &int_var, &char_var, string_var);- the leading while space is to ask scanf to ignore white space(including niewline) characters

- Other alternatives to flush the

\nin input buffer include usinggetchar()after ascanf()call, using%*c, but the best is to use fgets() to get a line stead of using scanf

- e.g.

printf() and scanf() families

|

|

- Prints to a file stream instead of

stdout

|

|

- Prints to a character array instead of

stdout

|

|

|

|

- Reads from a file stream instead of

stdin

|

|

- Reads from a string instead of

stdin

Demo Task 7

fgets():

|

|

fscanf():

|

|

3.10 I/O Redirection

process modifies its file descriptor table entry so that it points to a different entry in the system file table.

- Recall: to access a file, a process uses a file descriptor, which is an index into the process file descriptor table, which in turn points to an entry in the system file table.

cat: reads a file and outputs tostdout.cat test > my.file

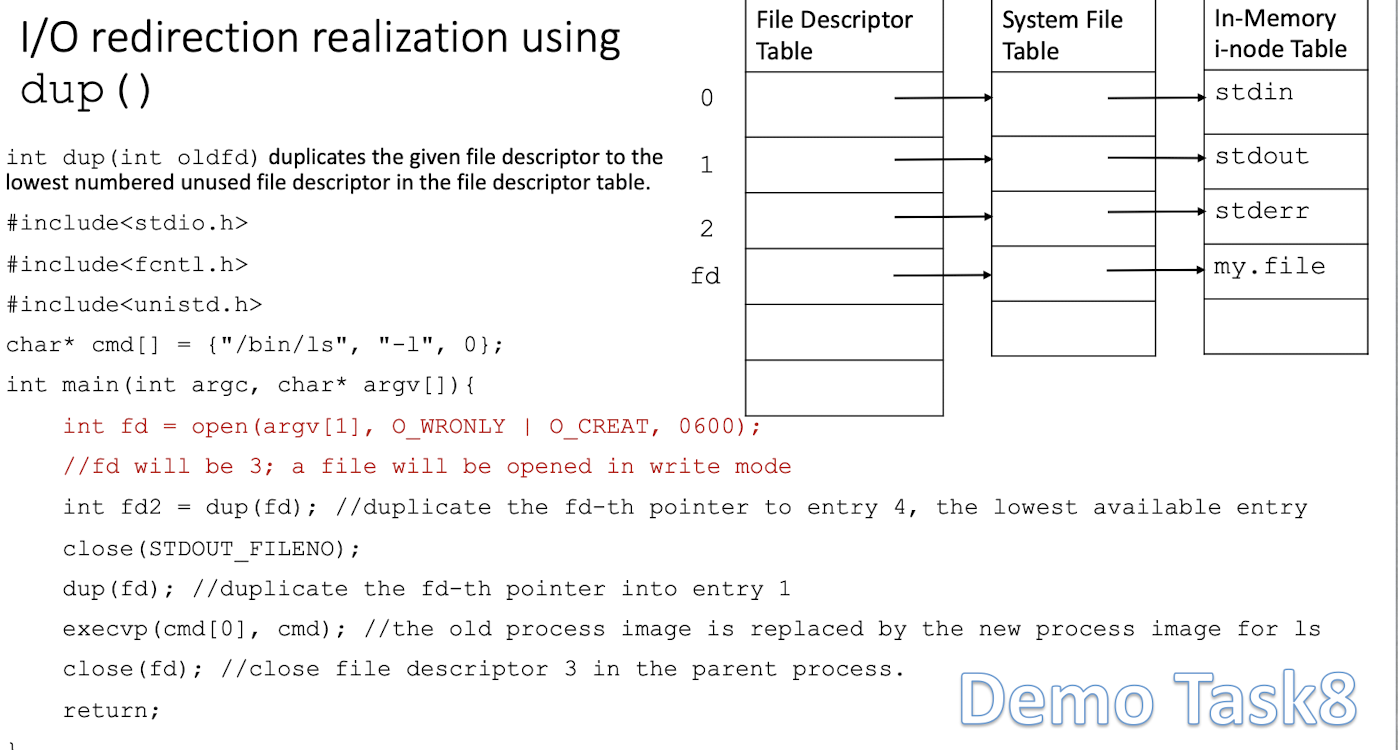

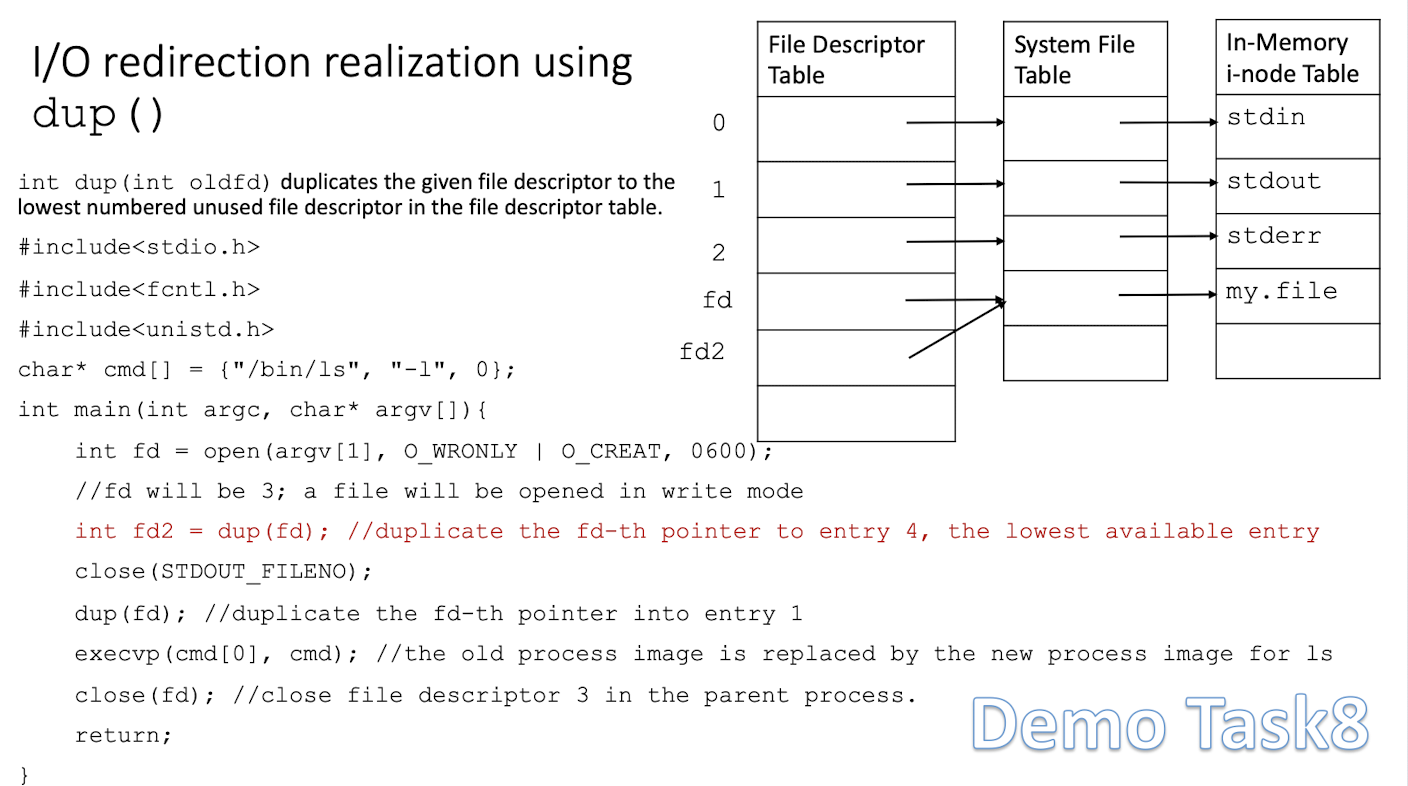

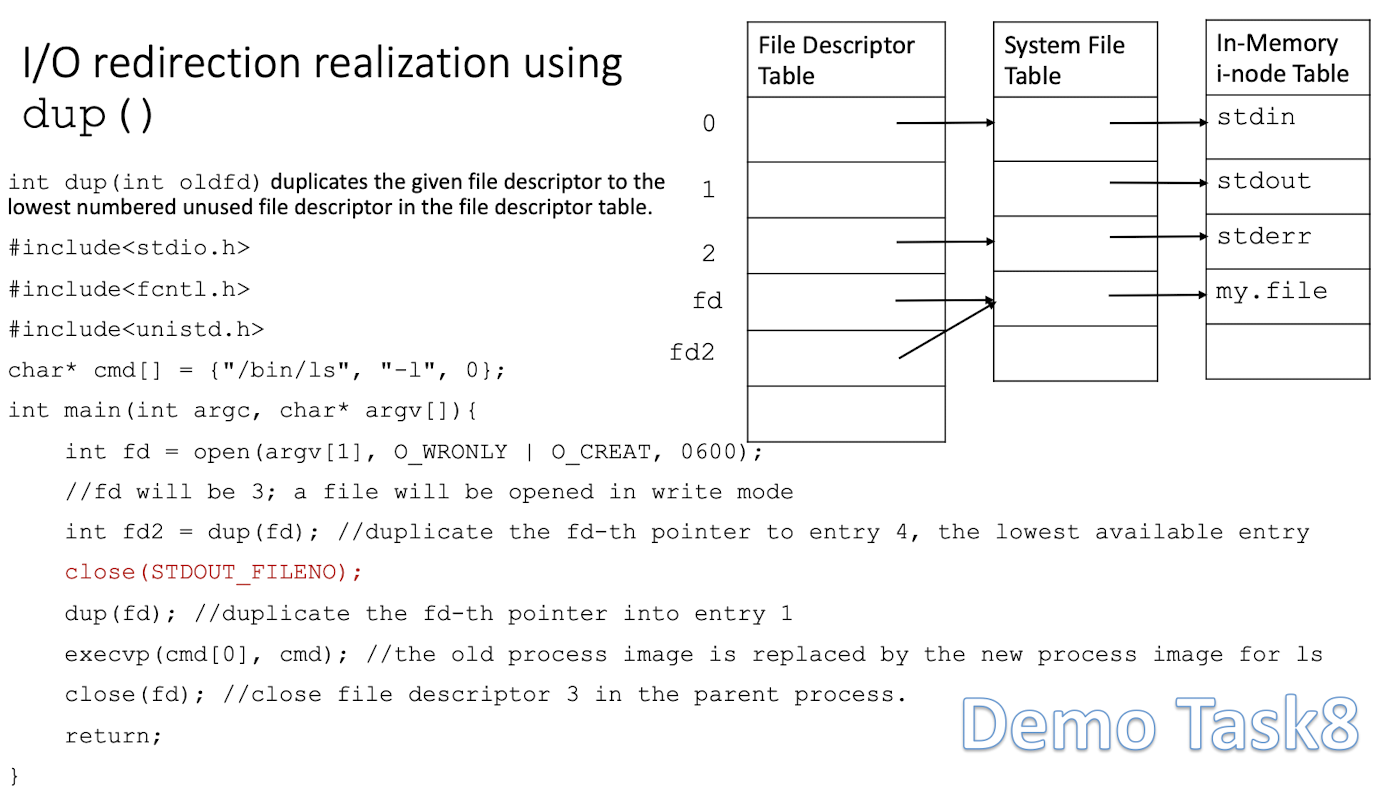

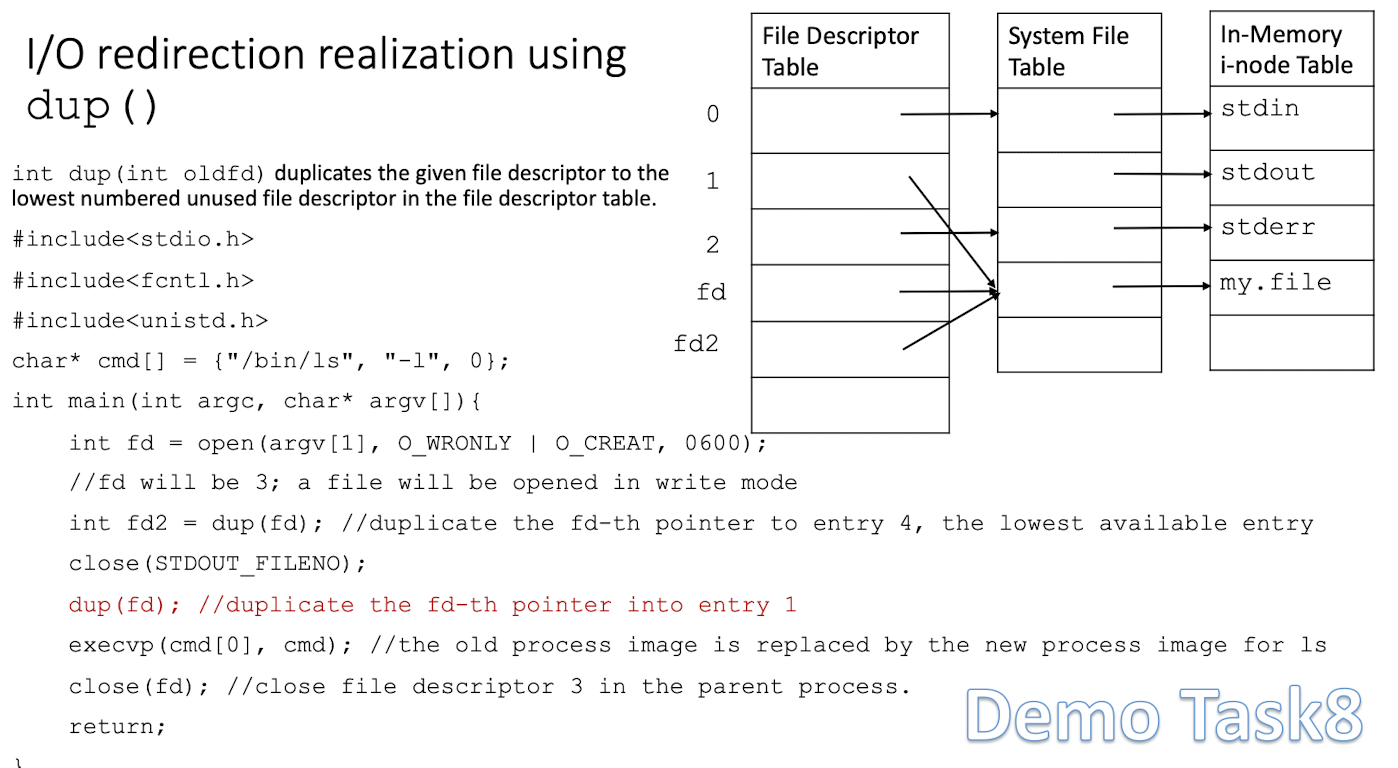

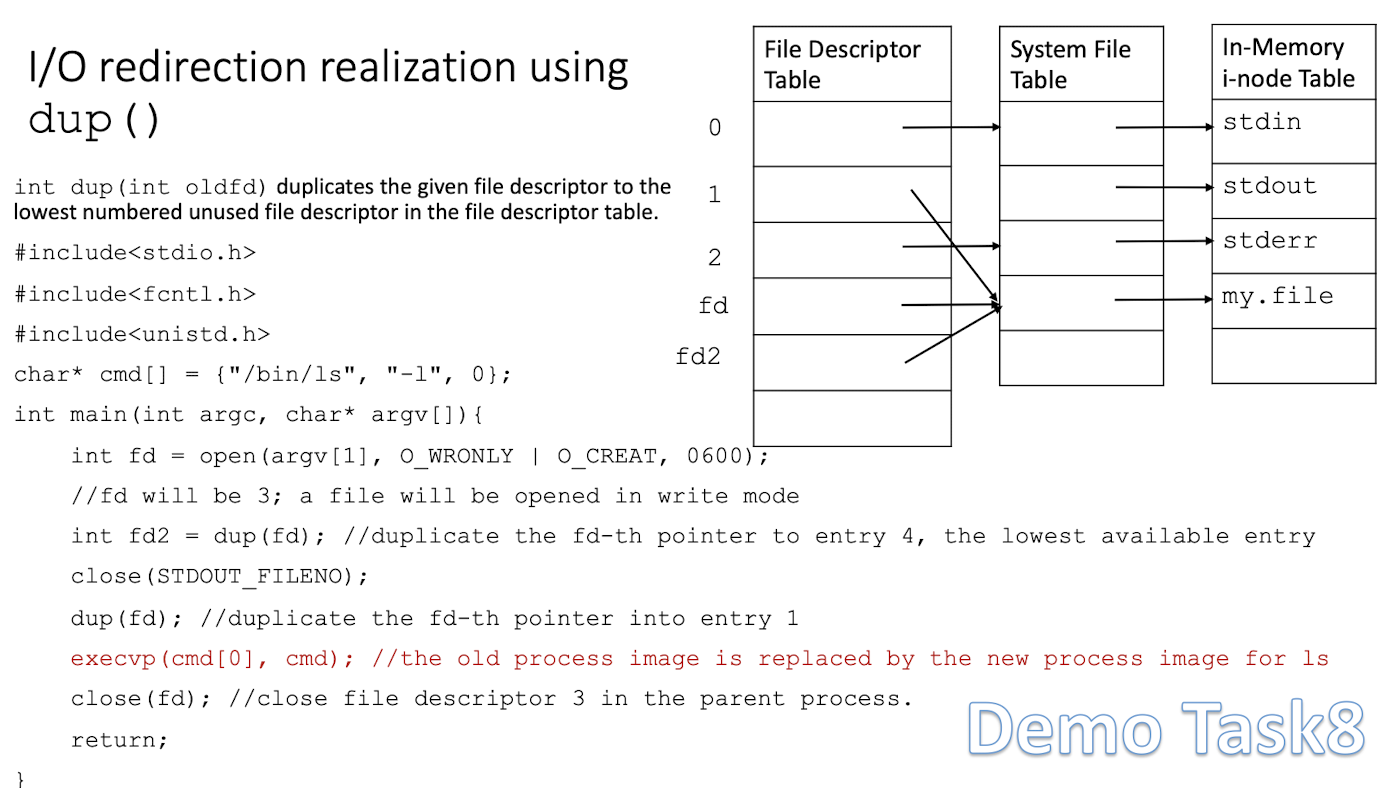

3.10.1 I/O redirection realization using Table dup()

int dup(int oldfd)duplicates the given file descriptor to the lowest numbered unused file descriptor in the file descriptor table.

Demo Task 8

|

|

3.10.2 Communication between parent/child via pipe

-

System call

pipe()returns two file descriptors by whilch we can access the input/outpur of a pipe(and I/O mechanism) -

int fd[2]; -

int pipe(int fd[2]);- Return: 0 success; -1 error

Demo Task 9

|

|

4 Device Driver

- What is a device driver?

- Related OS infrastructure

- Devices and files

- Major design issues

- Types of device drivers

4.1 What is a device driver?

- Device driver is a special kind of library, which can be loaded into the OS kernel, and links application program with the I/O devices

4.2 Related OS infrastructure

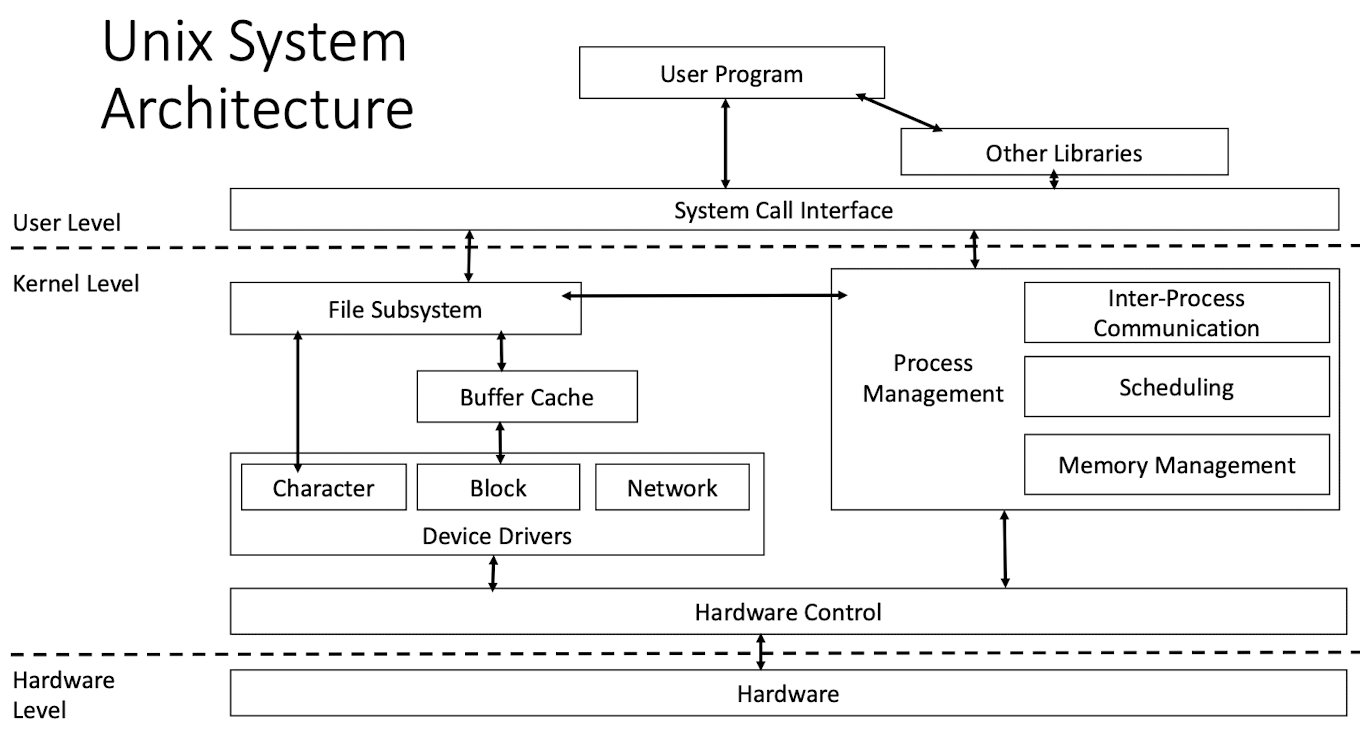

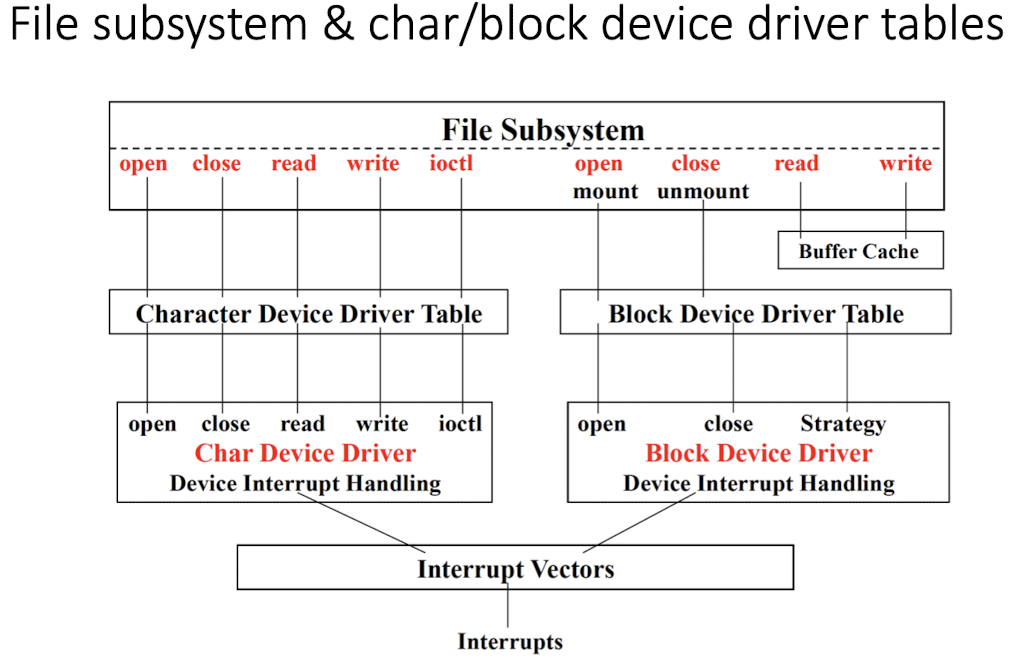

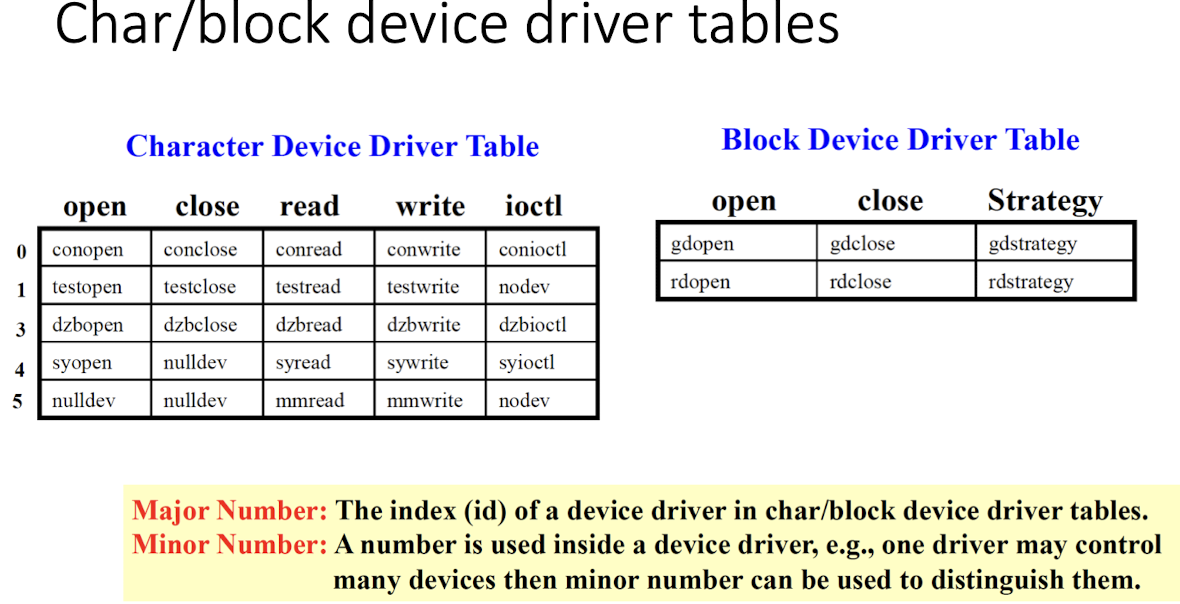

- Unix system architecture

- File subsystem and its relations with char/block device driver tables

- Char/block device driver tables

- Most of device derivers are character device drivers, like printer; block device driver operats on massive file system, like disk, CD-ROM, etc.

Advantages to separate device drivers from the OS

- For OS designer

- Devices may not be available when an OS is designed.

- no need to worry about how to operate devices (set up registers, check statuses, …).

- Focus on OS itself by providing a generic interface for device driver development.

- For Device driver designers

- Do not need to worry about how I/O is managed in OS (how to design kernel data structures to efficiently operate devices, …)

- Focus on implementing functions of devices with device-related commands following the generic I/O interface

4.3 Device and Files

devices are treated as special files.

A file is associated with an inode. We can use mknod <file_name> <c or b> <major_number> <minor_number> to create a special filr for a device file

When we create a special file (an inode) for a device file, we associate major/minor numbers with the file (the inode).

Major number associated with a special file is used to identify its corresponding device drivers in the kernel.

4.3.1 Character/Block Device Files

- Two types of device files: character and block

[Example]

|

|

4.4 Major Design Issues

OS/Device Driver Communication Device Driver/Hardware Communication

Device Driver Operations

- Interpret commands received from OS

- Schedule multiple requests for services

- Manage data transfer across both interfaces

- Accept & process hardware interrupts

- Maintain the integrity of the device’s and kernel’s data structures

4.5 Types of Device Drivers

Differences in the way that device drivers communicate with Linux

- Block

- Character

- Network

4.5.1 Block Device Driver

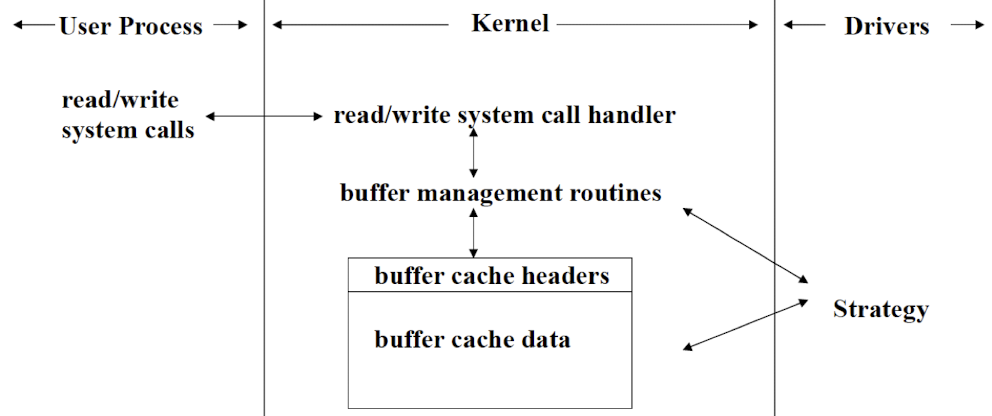

- Communicate with the OS through a collection of fixed size buffers

- OS manages a buffer cache; satisfy user requests for data by accessing buffers in the cache.

- Driver is invoked when requested data is NOT in the cache; when buffers in the cache have been changed and must be written out (write back to the devices).

- By using buffer cache, block drivers are insuxlated from the many details of user requests; only need to handle requests from the OS to fill or empty fixed size buffers.

- Many support devices contain file system

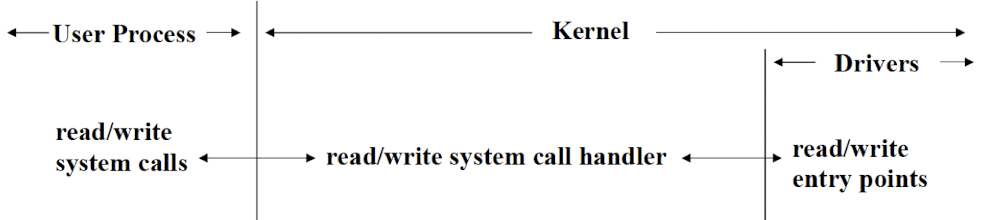

4.5.2 Character Device Driver

handle I/O requests of arbitrary size; support almost any type of devices.

- Handel data a byte at a time(keyboard);

- or work best with data in chunks smaller or larger than the standard fixed size buffer used by device driver (e.g. ADC)

[Communication structure]

Difference between block & character deivers

- Block driver – only interacts with buffer cache

- Character driver – directly interacts with user requests from user processes

- I/O requests are directly passed (essentially unchanged) to the drivers from the user processes

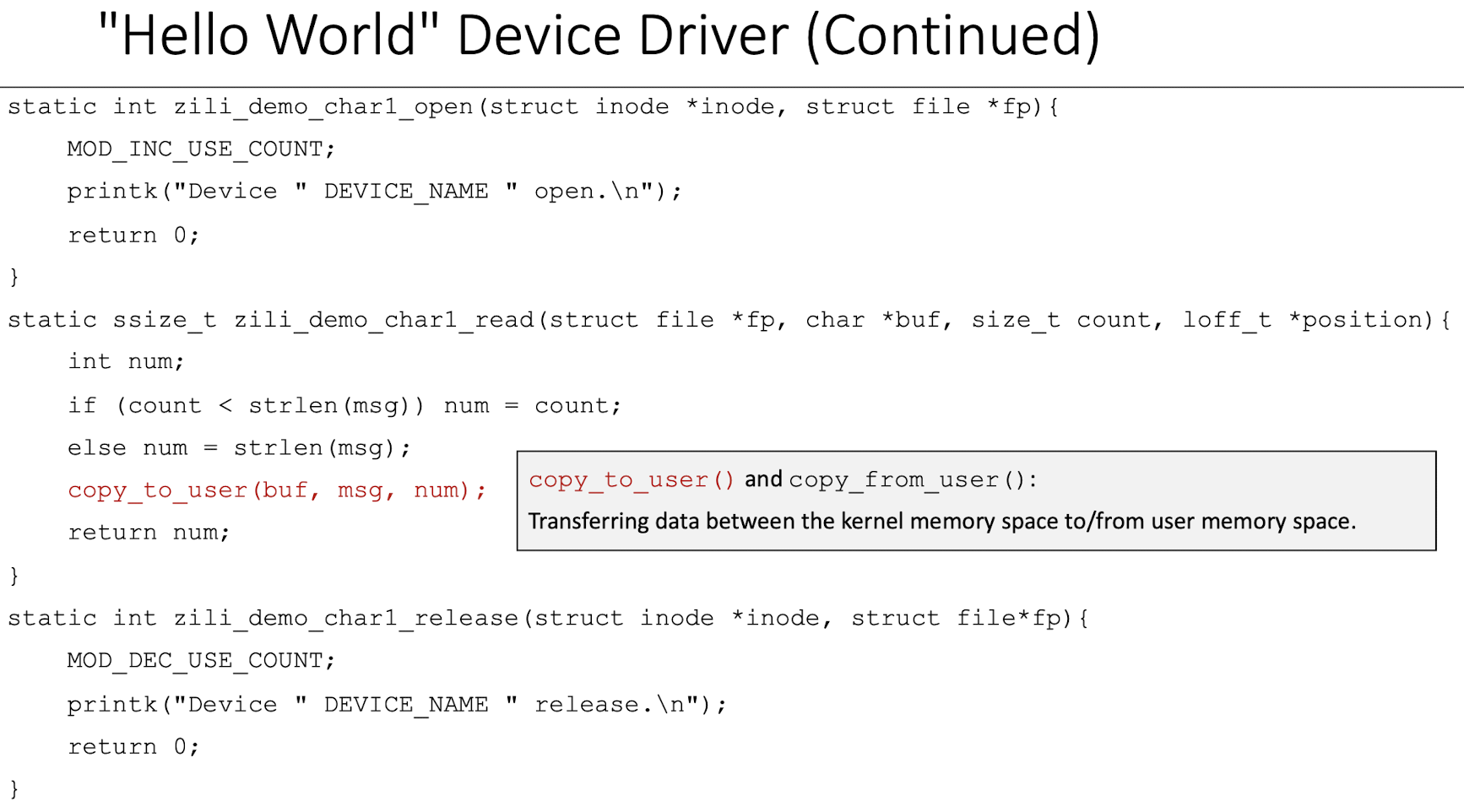

- Character driver is responsible for transferring data directly to/from the kernel memory space and the user memory space.

4.5.3 General Programming Considerations

- Device drivers are parts of the kernel and not normal user processes, which means we can only use the kernel routines in device driver programs, particularly C library functions or system calls for user level cannot be used.

- Some kernel routines may have the same names as C library functions, but they are of totally different implementations.

- Make frugal use of stack (local arrays & recursive function calls), as the stack space in the kernel is limited and not expandable.

- Be aware of floating-point arithmetic: may cause incorrect results

- Be aware of busy wait: may lock up the whole system

Summary

A device driver is a computer program that glues OS and its I/O devices together.

A device is treated as a special file in Unix.

There are three types of device drivers in Linux based on the different communication manner between device drivers and OS: block, character, and network.

5 Character Device Driver Development

two generic interfaces are related to character device driver development

- User programs: devices are treated as special files and users can only access devices through file operation system call (such as open, close, read, write, etc.), just like accessing regular files.

- Kernel: provides a generic interface and kernel routines for all device drivers to implement functionalities and register functions into the kernel data structures (such as char/block device driver tables).

5.1 The Interface for User Programs

- Device are treated as files: user programs access devices through file operation system calls.

- Each file has an inode, and each device driver has a major number.

- When using a device driver in user programs, we need to create a special file by associate its major number (driver) with an inode, e.g.

mknod /dev/lab1 c 251 0

5.2 Device Driver Development

Two Tasks:

- Implement functionalities based on the generic interface

- Register the device driver into the kernel data structure (the char/block device driver table)

The major number is the ID of a device driver

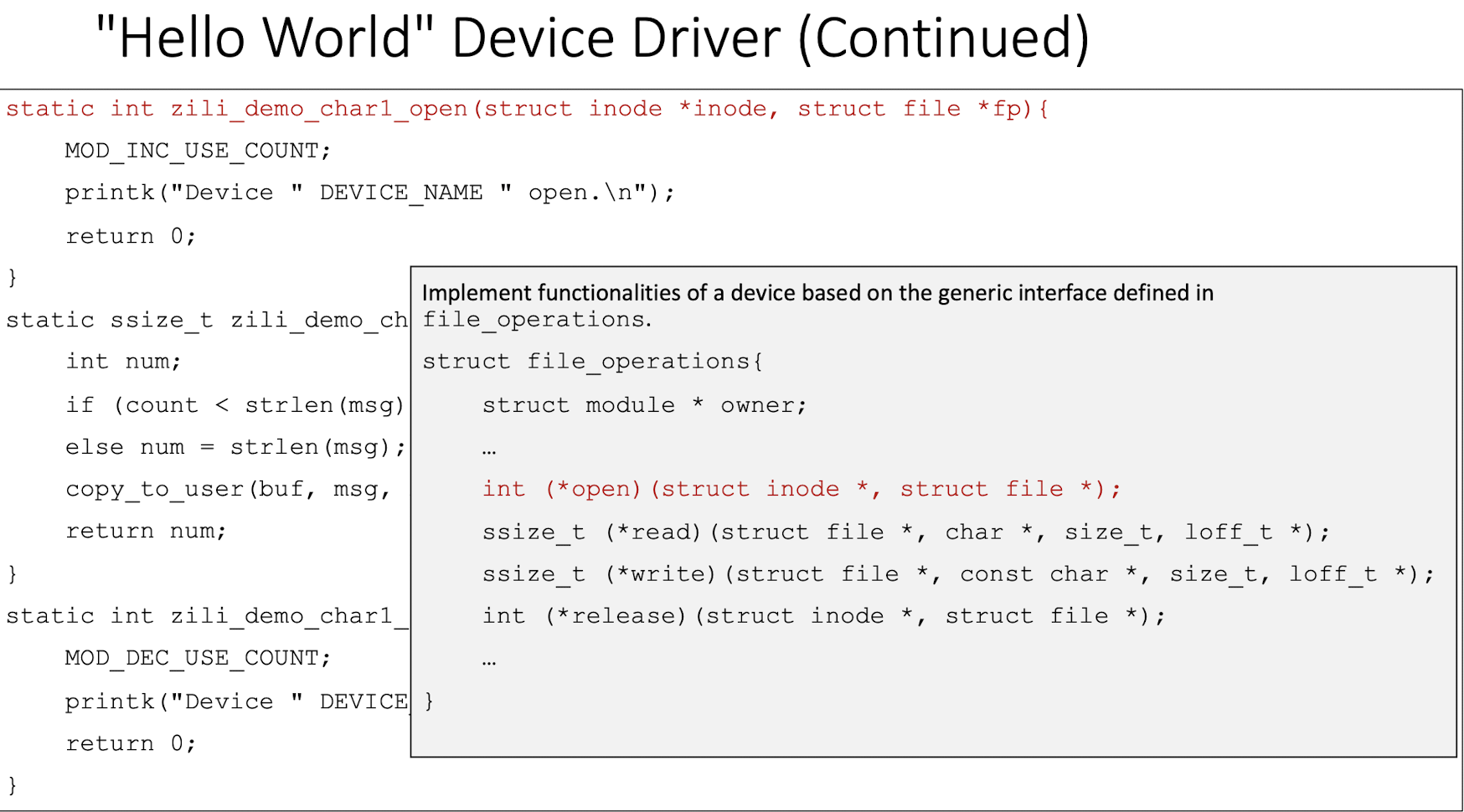

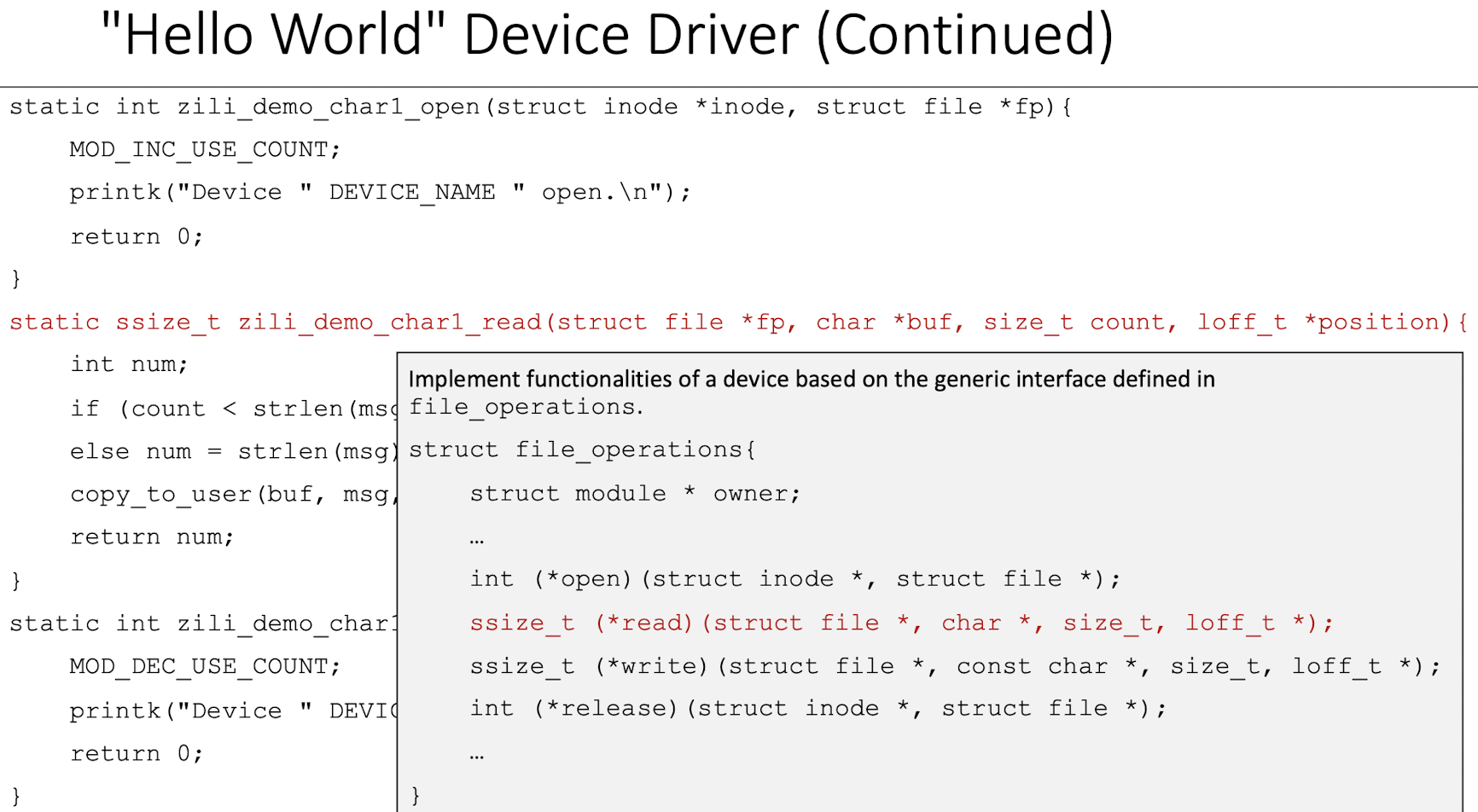

5.3 The Generic Interface for Char Device Driver in Linux

- Data structure called

file_operationsis defined in<linux/fs.h>. It is basically an array of function pointers.

|

|

- To develop a char driver, we need to implement the corresponding functions for a device based on the above generic interface.

Demo task 1

|

|

|

|

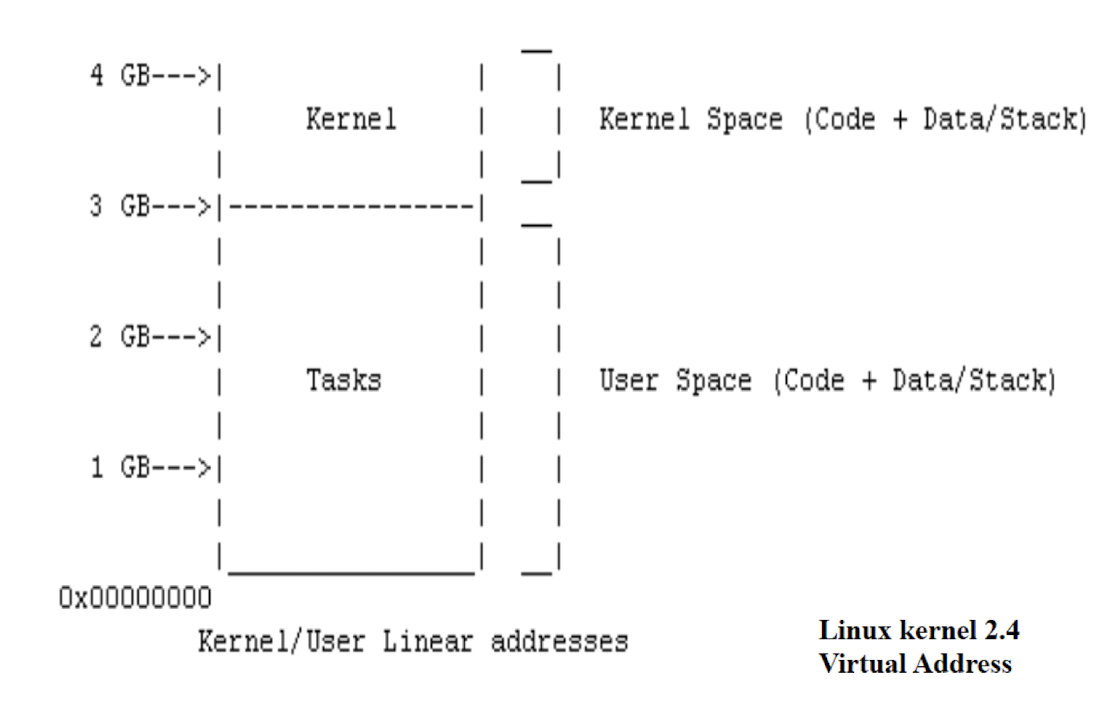

5.4 Kernel Memory Space and User Memory Space

- The kernel virtual memory address space and user virtual memory address space are separate in Unix.

- The resources that only kernel can access are also called the “kernel land”, while the resources that the user can access are also called the “user land”.

- declaration: not only declare, but memory allocation

- definition: not only define, but implementation

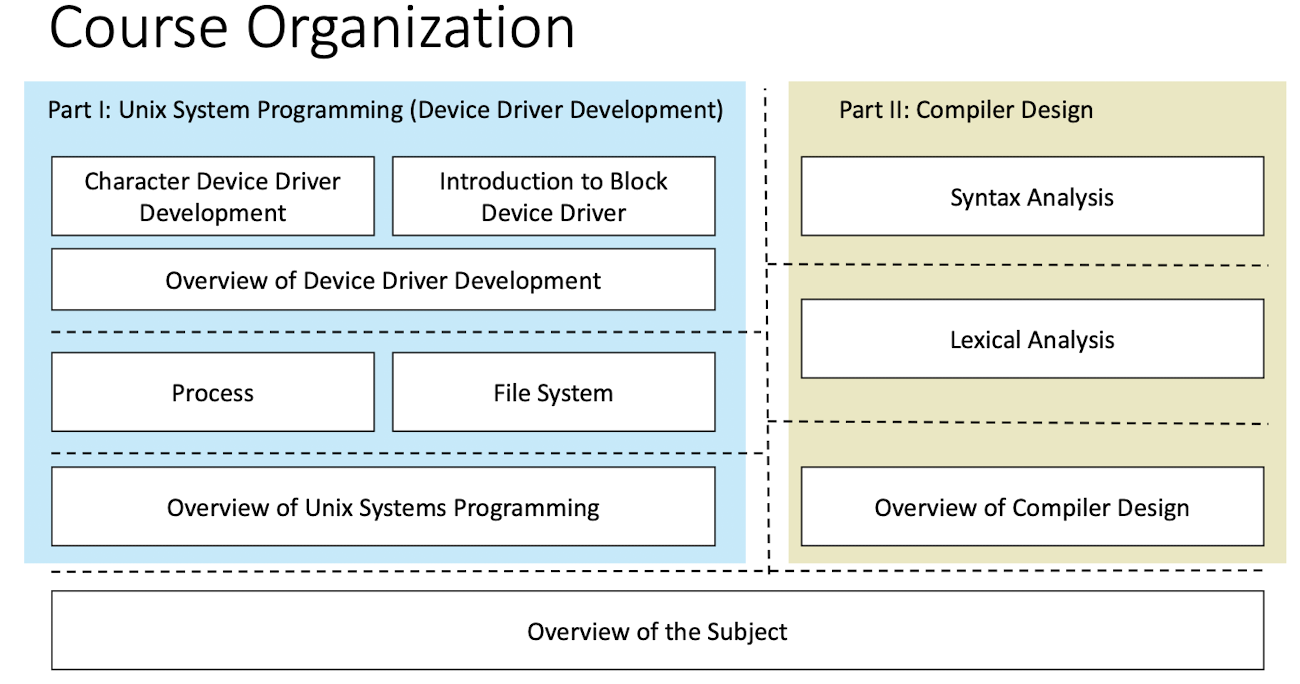

6 Complier Design

- Overview of Compiler Construction Syntax and semantics of programming languages; language translation approaches; tasks of a compiler; the compiler process.

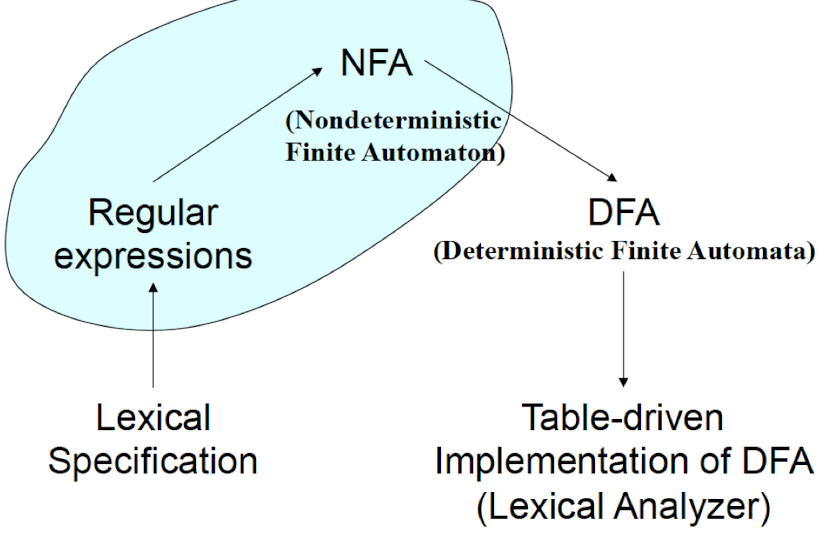

- Lexical Analysis: Tasks of lexical analysis; specifying tokens by regular grammars and regular expressions; recognizing tokens by Finite Automata (FA); construction of FA from regular expressions; converting NFA to DFA; simulating DFA.

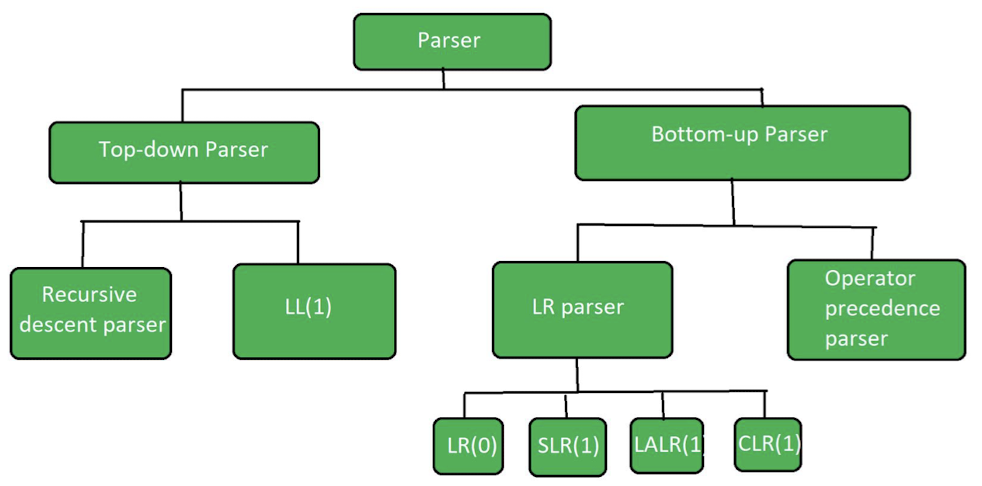

- Syntax Analysis: Tasks of syntax analysis; specifying language constructs by context-free grammars; BNF; derivation; parse and syntax trees; recognizing language constructs by Pushdown Automata; top-down and bottom-up parsing methods.

- Code Generation: Intermediate compilation phases; symbol table; intermediate code generation; code optimisation; code generation.

6.1 Complier Overview

Complier: A well-established discipline

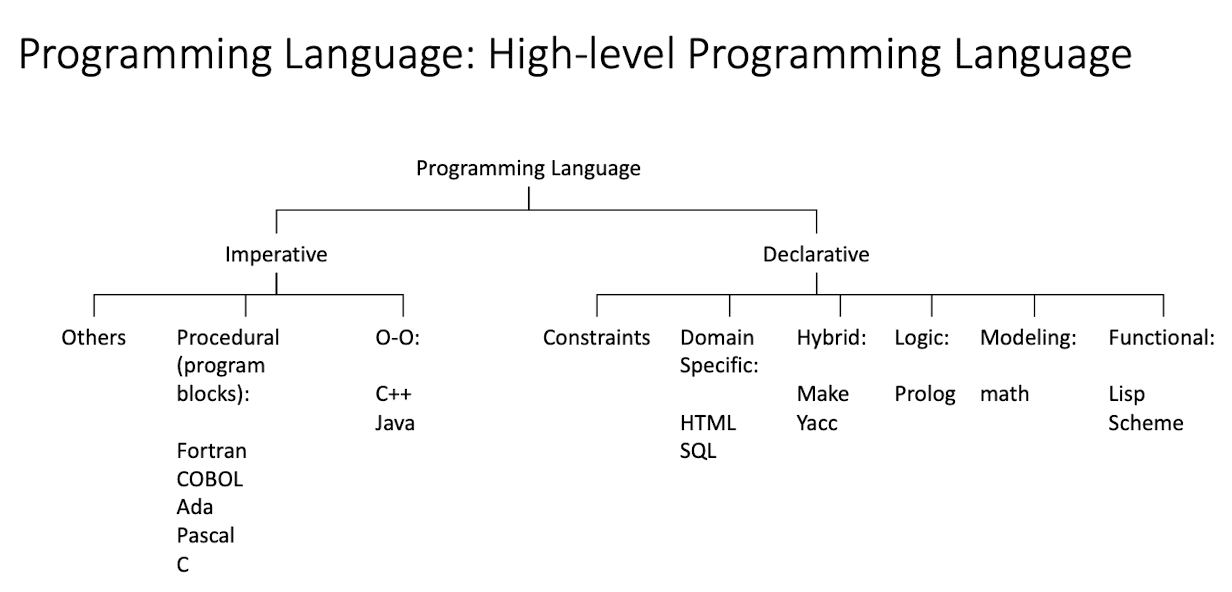

- Programming languages: high-level vs. low-level

- Complier

- Phases of a complier

Programming Languages: Machine Language

Everything is a binary number: operation, data, address

- In MIPS 2000:

0010 0100 1010 0110 0000 0000 0000 0100- means

$t5 + 4 -> $6

Programming Languages: Assembly Language

- Symbolic representation/mnemonics of machine language

add $t6, $t5, 4

Benefit of High-level Language

- human readable

- Hide unnecessary details, so have a higher level of abstraction, increased productivity

- Make programs more robust: information is specified before its use, enabling subsequent error checking at compile time

- Make programs portable: the same program can be compiled on different machines

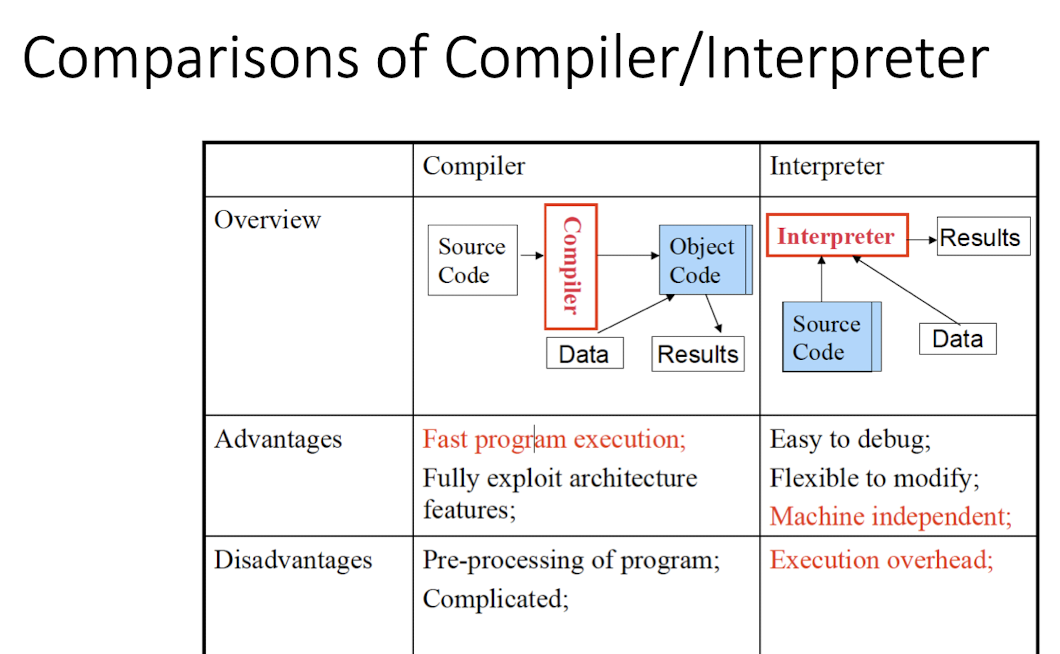

6.2 Translation Mechanism

- Development time translation: Compilation

- Translate source programs in one language into executable programs

- C, C++

- Runtime translation: Inerpretation

- Read source programs, understand and produce execution results in the meantime

- line by line

- Perl, Shell commands

- Hybrid: Compilation + Interpretation

- Java, complied into byte code, and then interpreted by JVM during runtime

6.3 Complier and Phases of a Compliation

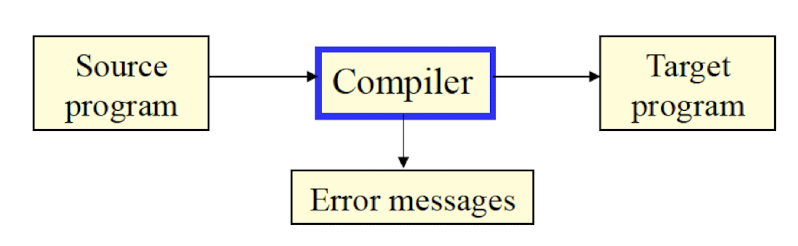

Definition

- A compiler is a software that takes a program written in one language (called the source language) and translates it into another (usually equivalent) program in another language (called the target language).

- Also reports errors (bugs) in the source program.

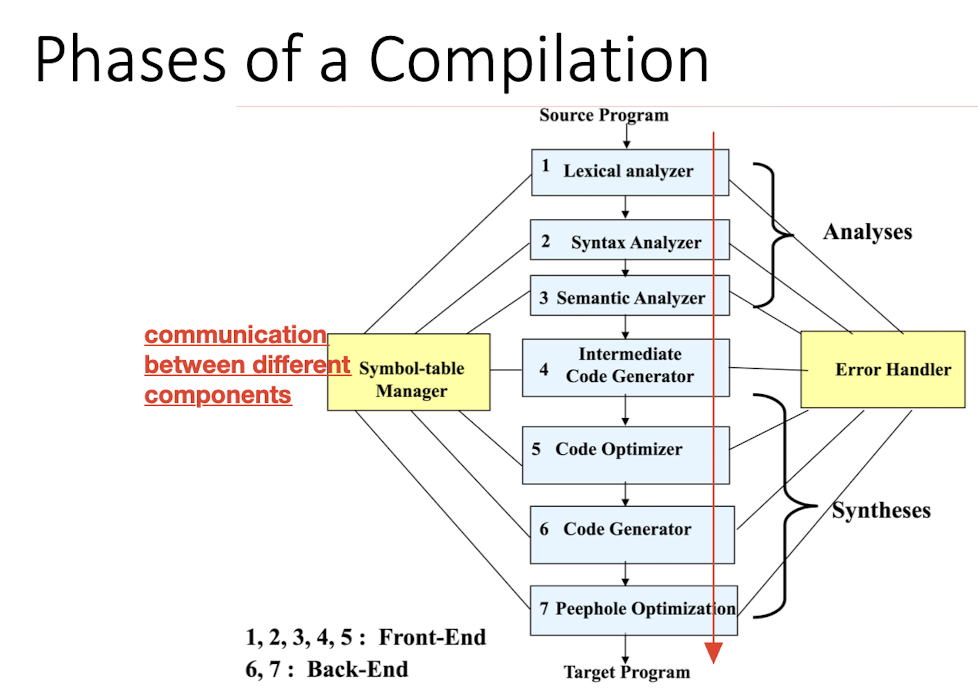

[Phases of a Compliation]

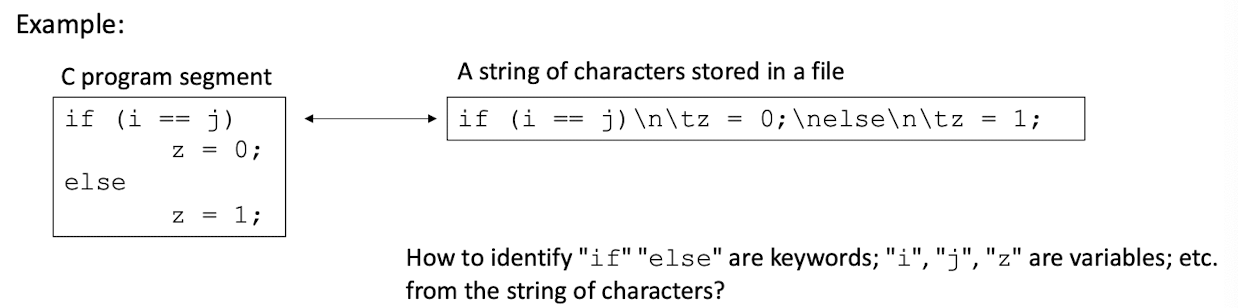

6.3.1 Lexical Analysis

- Scan the source program and group sequences of characters into tokens.

- A token is the smallest element of a language

- A group of characters (e.g., a series of alphabetic characters form a keyword; a series of digits form a number).

- The sub-module of the compiler that performs lexical analysis is called a lexical analyzer.

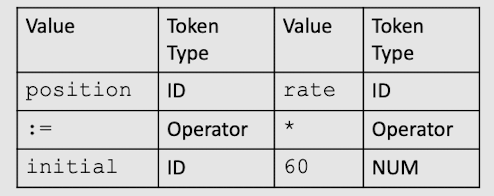

- Example:

position := initial + rate * 60 - Read one by one

6.3.2 Syntax Analysis

- Once the tokens are identified, syntax analysis groups sequences of tokens into language constructs.

- e.g., identifiers, numbers, and operators can be grouped into expressions.

- e.g., keywords, identifiers, expressions, and operators can be combined to form statements.

- The sub-module of the compiler that performs syntax analysis is called the parser/syntax analyzer.

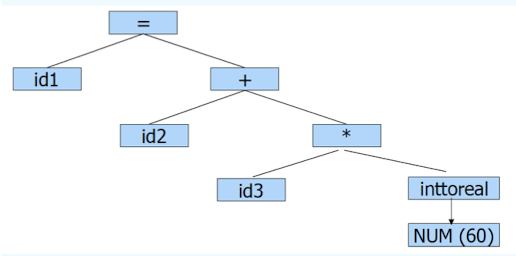

6.3.3 Syntax(Parse) Tree

- Result of syntax analysis is recorded in a hierarchical structure called a syntax tree.

- Each node represents an operation and its children represent the arguments of the operation.

- Evaluation begins from bottom and moves up.

- E.g., parse tree for

position := initial + rate * 60

6.3.4 Semantic Analysis

- Put semantic meaning into the syntax tree:

- syntax analysis recognizes grammatical events;

- semantic analysis processes such events, e.g., type checking, or triggering corresponding intermediate code generation

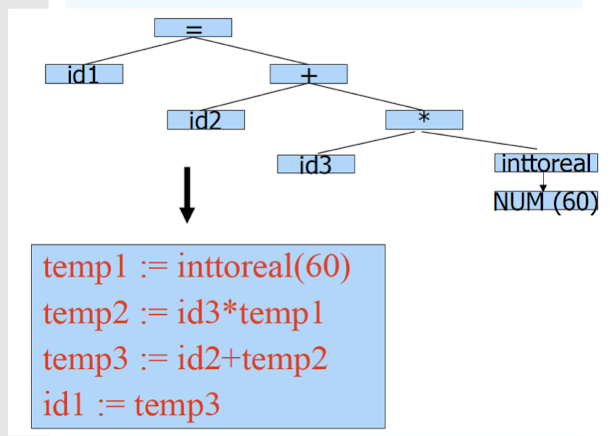

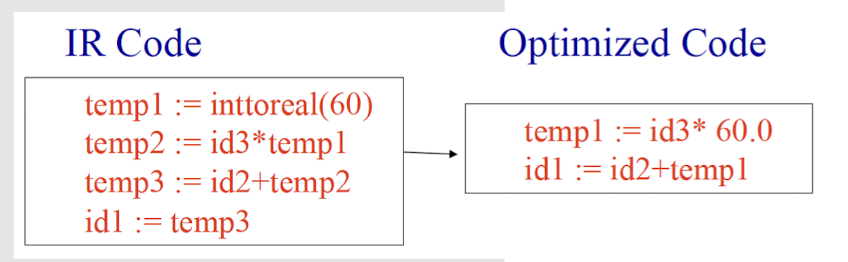

6.3.5 Intermediate Code Generation

- Generate IR (Intermediate Representation) code:

- Easier to generate machine code from IR code.

6.3.6 Code Optimization

- Modify program representation so that program can run faster, use less memory, power, etc.

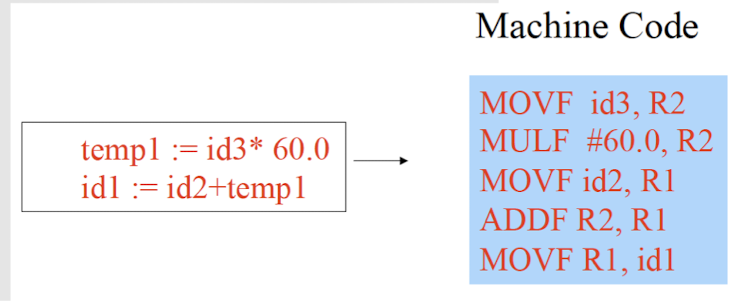

6.3.7 Code Generation

- Generate the target program

6.3.8 Distinction between Phases and Passes

- Passes: the times going through a program representation.

- 1-pass, 2-pass, multiple-pass compliation

- Language become more complex – more passes

- Phases: conceptual stages, or modules of the compiler

- Not completely separate: Semantic phase may do things that syntax should do

6.4 Lexical Analysis(I)

- Why we need lexical analysis? Its input and output.

- How to specify tokens: Regular Expression

- How to recognize tokens – two methods

- Regular Expression $\to$ Lex (software tool)

- Regular Expression $\to$ Finite Automata

Why need Lexical Analysis?

- Group the character into meaningful words

6.4.1 Input and Output of Lexical Analysis

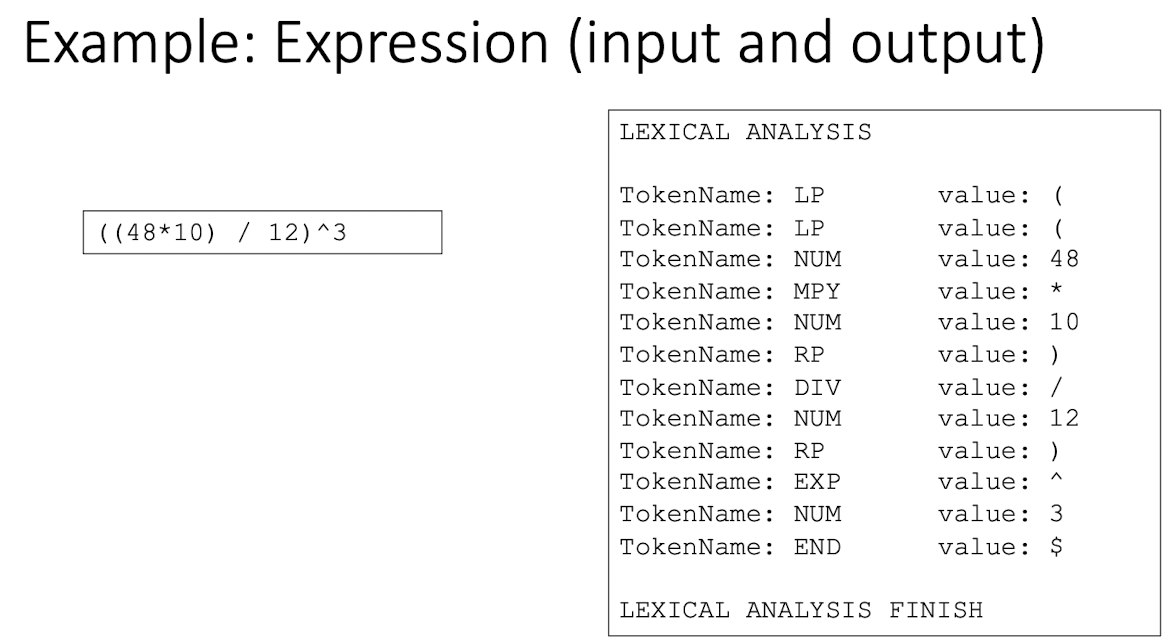

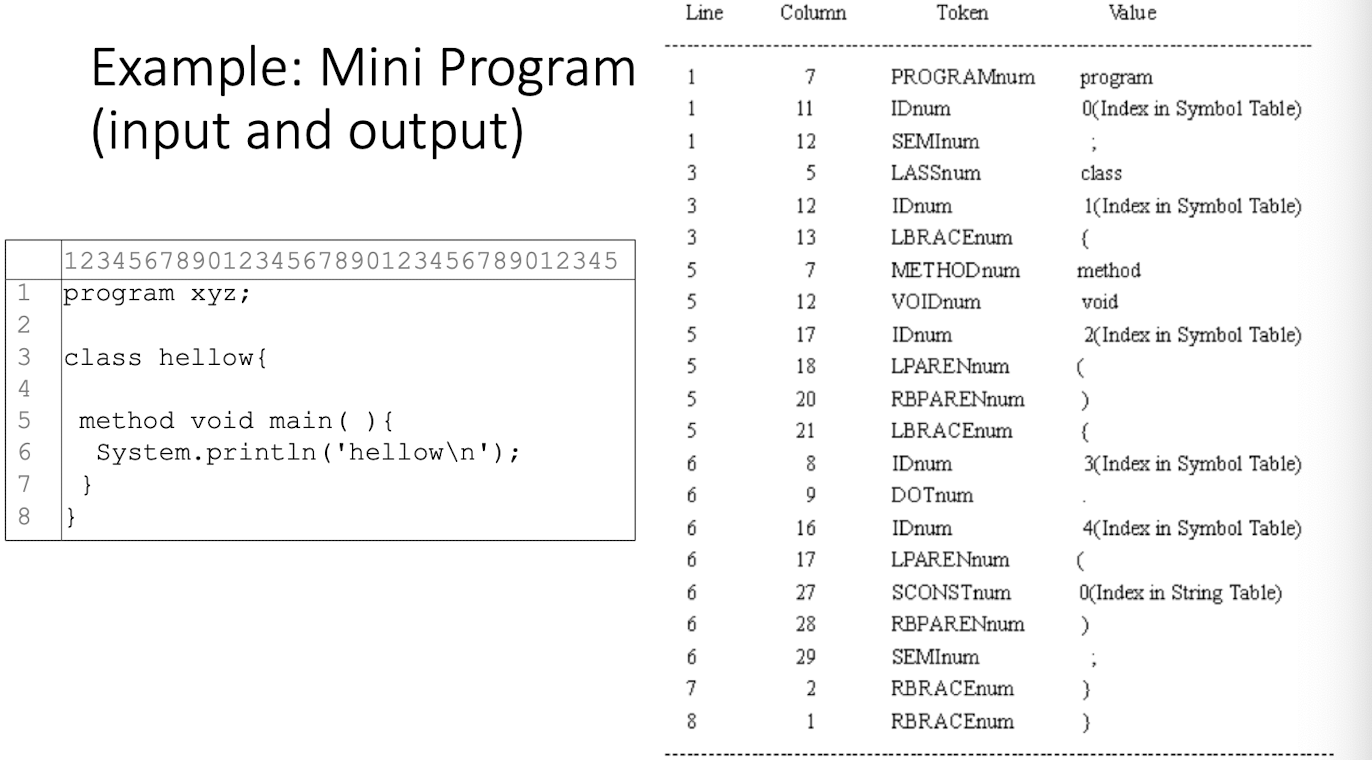

In lexical analysis, a source program is read from left-to-right and grouped into tokens. A token is a sequence of characters with a collective meaning.

Token

- A syntactic category

- In English: a noun, a verb, an adjective, …

- In a programming language: an identifier, an integer value, a keyword, a white space, …

- Tokens correspond to sets of strings with a collective meaning

- Identifier: strings of letters and digits, starting with a letter

- Integer value: a non-empty string of digits

- Keyword:

else,if,where, …

[Expression]

[Mini Program]

Reason for tokens

- Classify program substrings according to their syntactic role.

- As the output of lexical analysis, tokens are the input to the parser (syntax analysis)

- Parser relies on token distinctions

- Different tokens are treated differently by the parser(keyword vs. identifier)

Recognize tokens

- First, specify tokens using regular expressions (patterns)

- Second, based on regular expression, two ways to implement a lexical analyzer:

- Method 1: use Lex, a software tool

- Method 2: use finite automata (write your own program)

6.5 Lexical Analysis(II)

- Part II: Regular Expression

6.5.1 Regular Expression

Specify tokens

- A token is specified by a pattern: a set of rules that describe the formation of the token

- The lexical analyzer uses the pattern to identify the lexeme: a sequence of characters in the input that matches the pattern. Once matched, the corresponding token is recognized.

- For example: The rule (pattern) for identifier: letter followed by letters and digits

abc1andA1Bymatch the rule (pattern), hence they are identifier tokens;1Adoes not match the rule (pattern), hence it is not an identifier token.

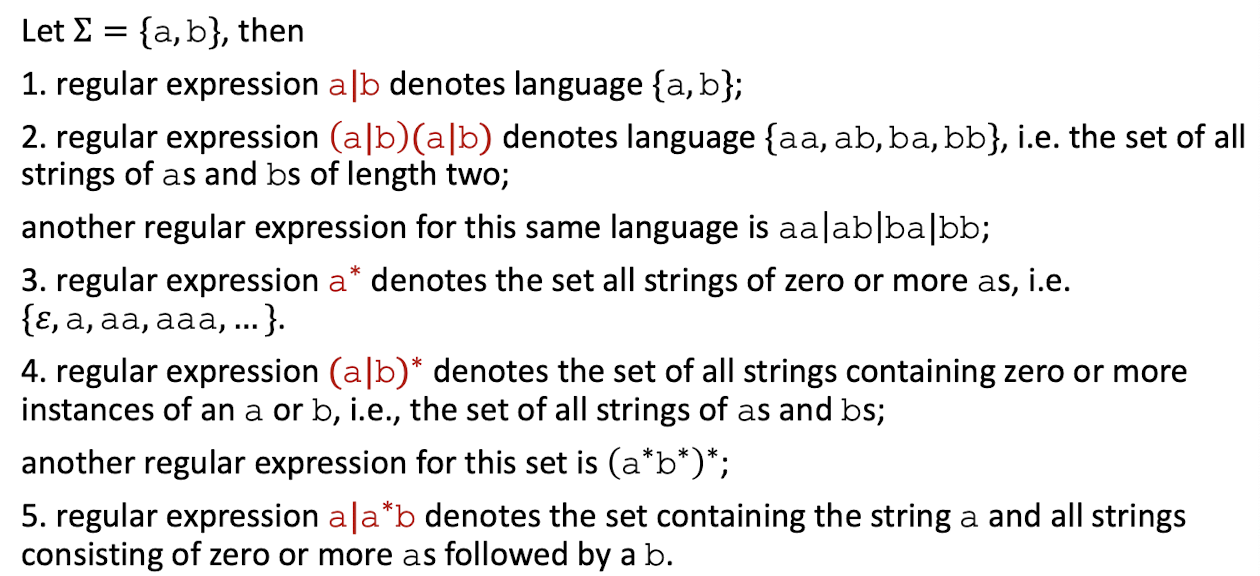

The rules for specifying token patterns are called regular expression. A regular set (regular language) is the set of strings generated by a regular expression over an alphabet.

6.5.2 Alphabet and Strings

- An alphabet (usually denoted as $\sum$) is a finite set of symbols.

- E.g. ${0,1}$ is the binary digits alphabet; ${a,b,c}$ is the English letter alphabet.

- A string $s$ over an alphabet $\sum$ is a finite sequence of symbols drawn from that alphabet.

- E.g.

01001is the string over $\sum_{\text{bin_digits}}$ $= {0,1}$ wxyasdis the string over $\sum_{\text{lower_case_letters}}$ $= {a,b,…,z}$- $ε$ is the empty string (without any symbol)

- E.g.

- The length of a string $s$ is denoted as $|s|$. E.g. $|ε|$ = 0; $|101| = 3$; $|abcdef| = 6$.

6.5.3 Kleene Closure and Language

- The Kleene closure of alphabet Σ, denoted as Σ∗, is the set of all strings, including the empty string , over the alphabet Σ.

- E.g. given alphabet Σ = {0,1}, then Σ∗ = {ε,0,1,00,01,10,11,000,001,….}

- Any set of strings over an alphabet Σ, i.e. any subset of Σ∗, is called a language.

- E.g. the empty set ∅, { }, Σ, and Σ∗ are all languages; abc, Def, D, z is a language over Σ letters = a, b, … , z, A, B, … , Z .

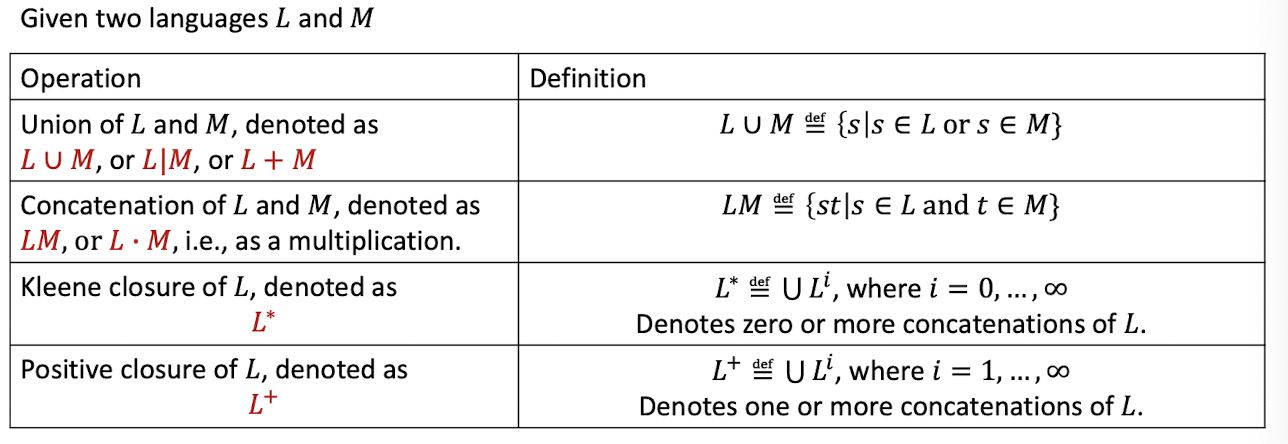

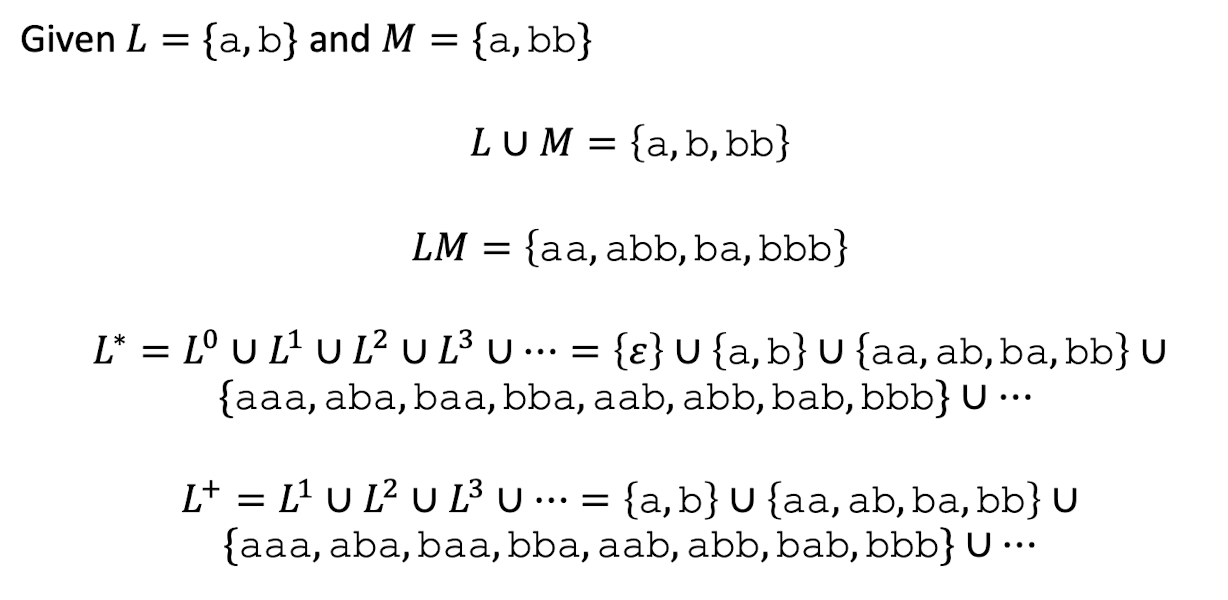

6.5.4 Operations on languages

- Particularly union, concatenation, Kleene closure, and positive closure.

Precedence

- Kleene closure $\succ$ concatenation $\succ$ union

- {1}|{2}{3}*

- Exponentiation (concatenating the same language) ≻ multiplication (concatenating different/same languages) ≻ addition (union)

- {1} + {2} $\cdot$ {3}^2.

Let $L={a,b,…,z,A,B,…,Z}$ and $D={0,1,2,…,9}$

6.5.6 Reaular Expressions

Let $\sum = {a,b}$

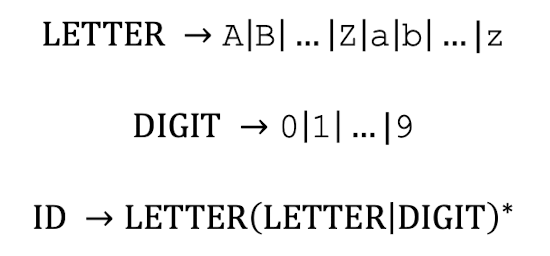

6.5.7 Identifiers in Pascal

- Pascal identifier: a string of letters and digits beginning with a letter.

- Regular definition

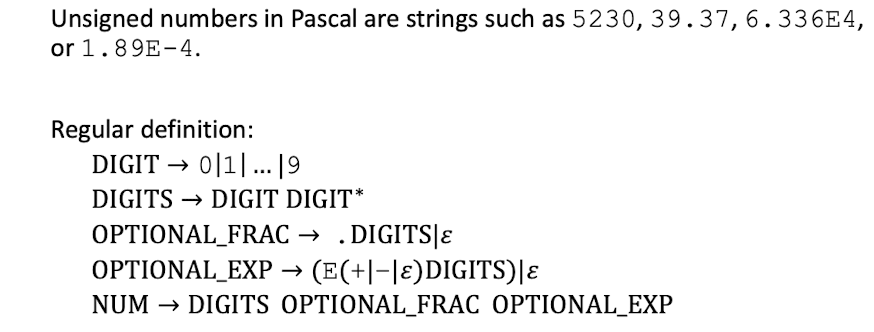

[Unsigned Numbers in Pascal]

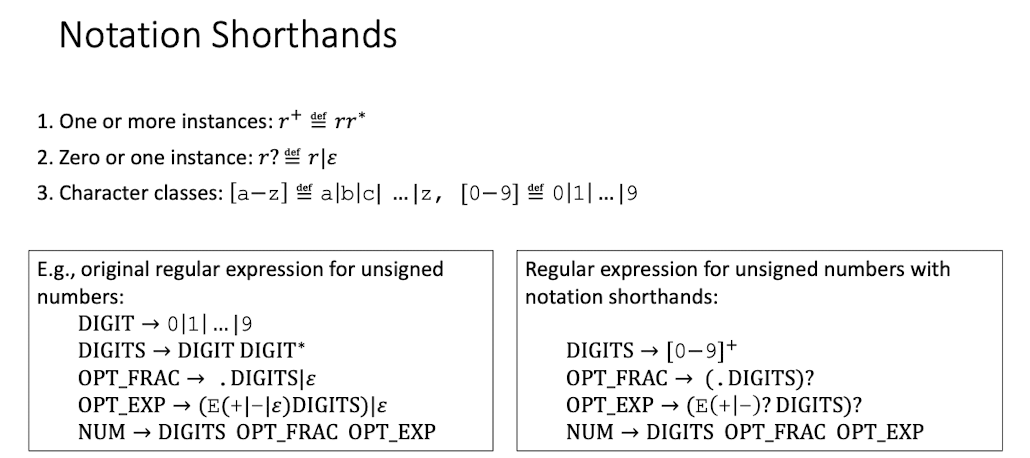

[Notation Shorthands]

6.5.8 Implementation of Lexical Analyzer

- After regular expressions are obtained, we have two methods to implement a lexical analyzer:

- Use tools: lex (for C), flex (for C/C++), jlex (for Java)

- Specify tokens using regular expressions

- Tool generates source code for the lexical analysis

- Use regular expressions and finite automata

- Write code to express the recognition of tokens

- Table drivern

- Use tools: lex (for C), flex (for C/C++), jlex (for Java)

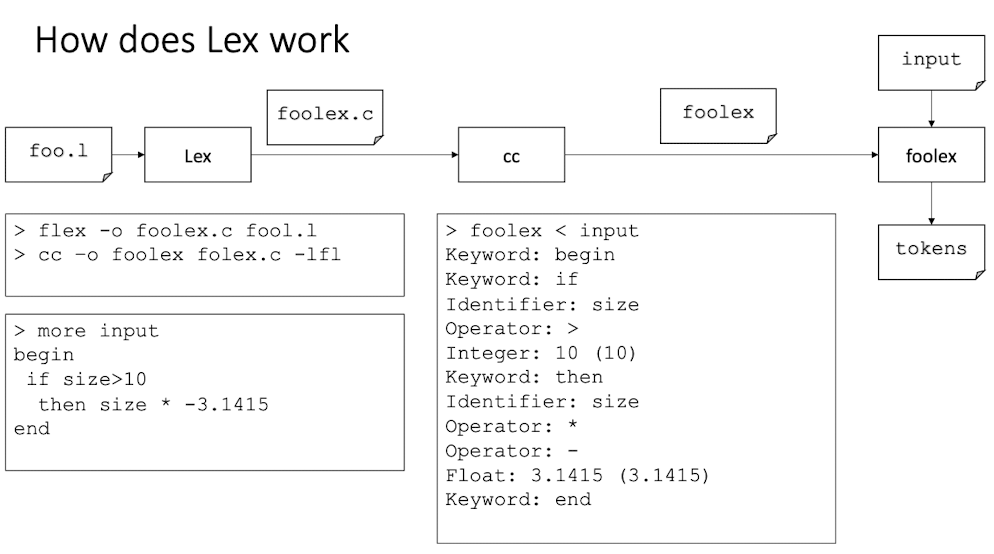

Lex: a lexical analyzer generator

Lex is a Unix software tool, automatically constructs a lexical analyzer.

- Input: a specification containing regular expressions written in the Lex language.

- Assumes that each token matches a regular expression.

- Need an action specification for each expression.

- Output: Produces a C program that can recognize the matching tokens and trigger the specified actions.

- Especially useful when coupled with a parser generator

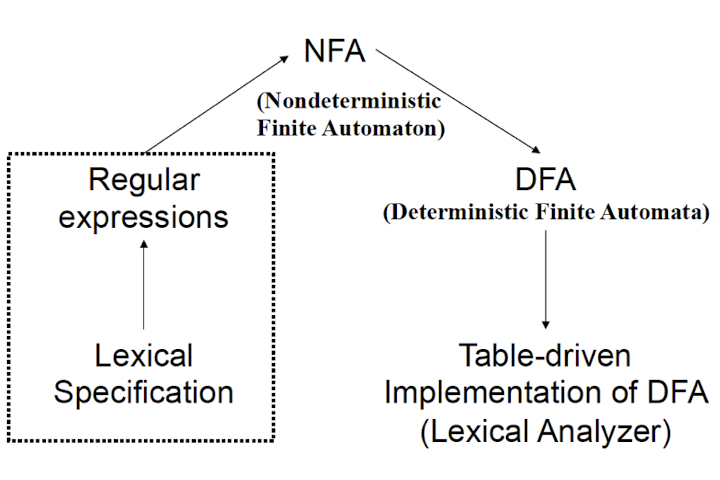

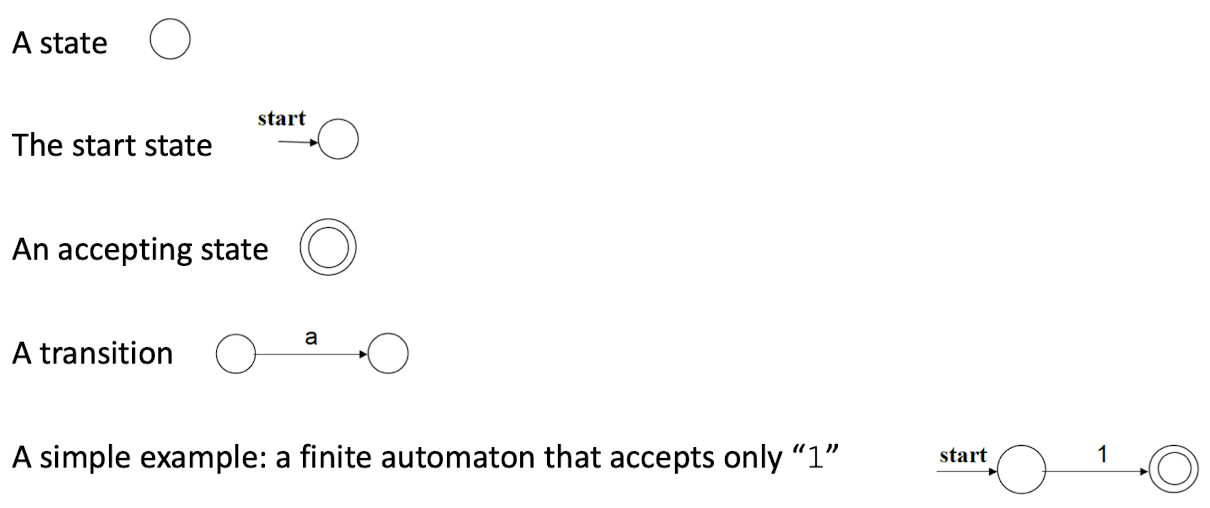

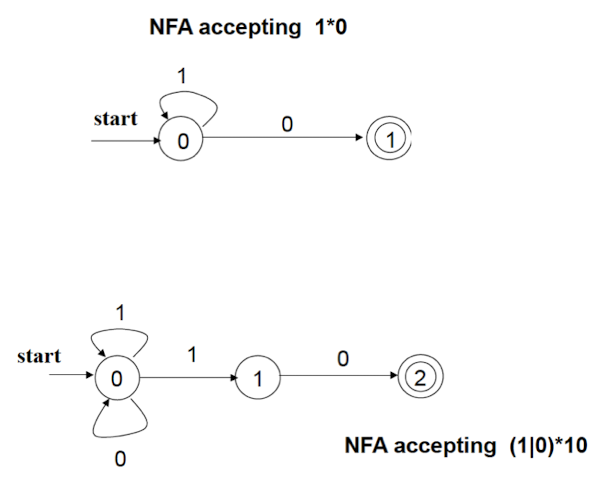

7 Lexical Analysis(III) - Finite Automata

7.1 NFA, DFA, and NFA $\to$ DFA Conversion

Recognizing Tokens

-

Regular Expression à Specify tokens

-

Finite Automaton à Recognize tokens

-

A language recognizer:

- Input: string x $\to_{\test{Recognizer for L}}$ $\to$ Ouputs “yes” if x $\in$ L, “no” otherwise

-

A recognizer for a language is a program that takes a string and answers “yes” if is a string of , and “no” otherwise.

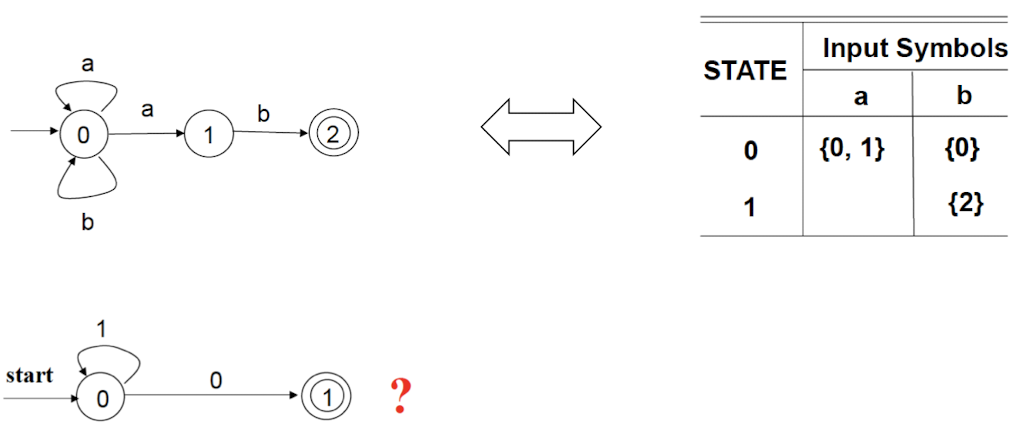

7.2 Nondeterministic Finite Automata (NFA)

- A Nondeterministic Finite Automaton (NFA) consists of 5 components (Σ,S,S_0,F,move).

- Σ is the input alphabet

- S is the set of states

- S_0 is the start state

- F $\subset$ S is the set of accepting states

- move is the transition function that maps state-symbol pairs to sets of states.

Transition Graphs

7.3 State Transition Table

The transition function of an NFA can also be implemented by a transition table, where the entries of rows are states and columns, respectively.

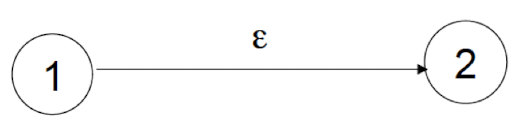

7.4 ε - Transition

A nother kind of transition, where the automaton transits from one state to another state without reading any input.

- NFA based recognitions (decisions) are hard to implement

- Can have multiple transitions from one input in a given state

- Can have ε-transitions Easy to form from regular expressions

- Hard to implement the recognition (decision) algorithm

7.5 Deterministic Finite Automata

A DFA is a special case of NFA:

One transition per input per state No ε-transitions

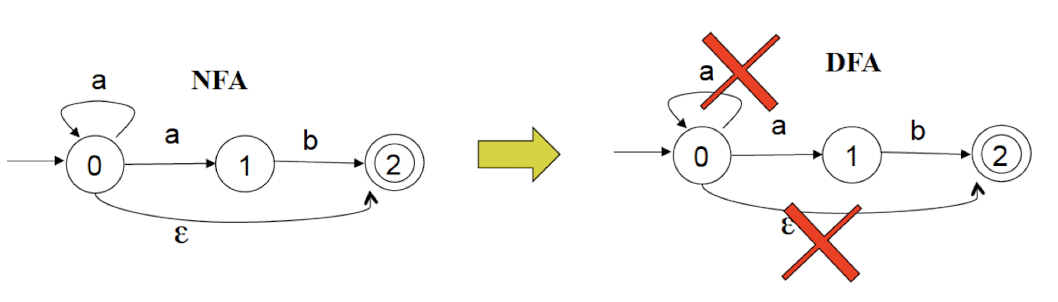

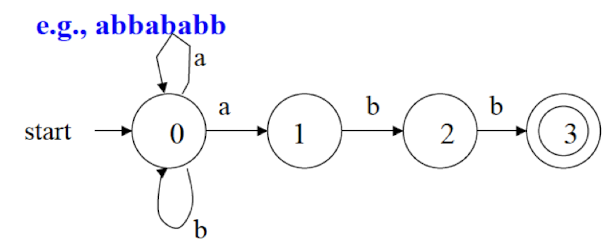

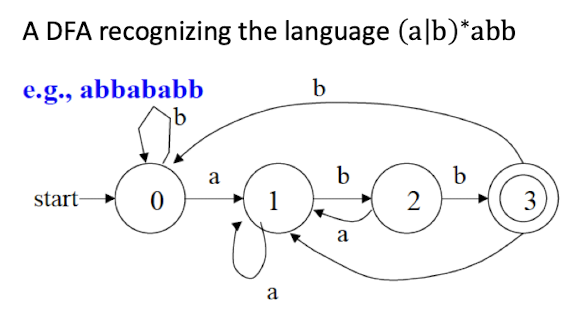

Examples of NFA and DFA Given alphabet

- NFA:

- Easy to generate strings.

- May go to anyone of several states given an input symbol.

- May go to another state when there is no input, due to -transition(s).

- DFA:

- Easy to both generate and recognize strings.

- Goes to only one deterministic state given an input symbol.

- Does not go anywhere when there is no input; does not have any ε-transition.

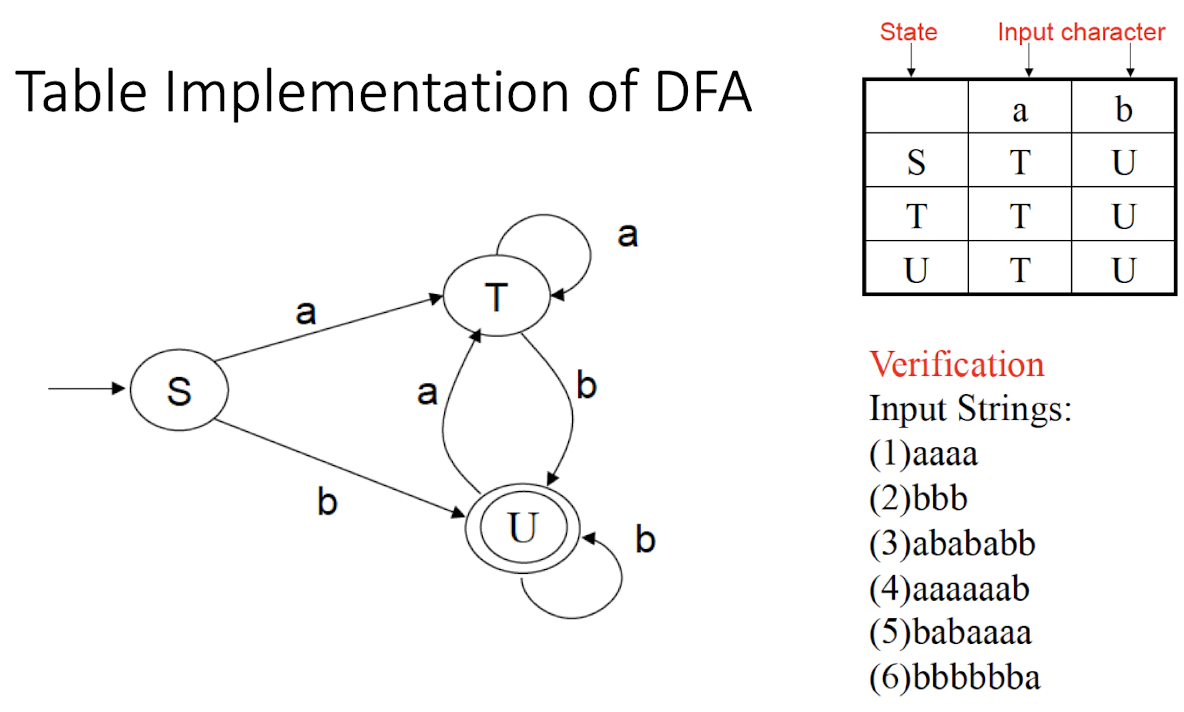

Table Implementation of DFA

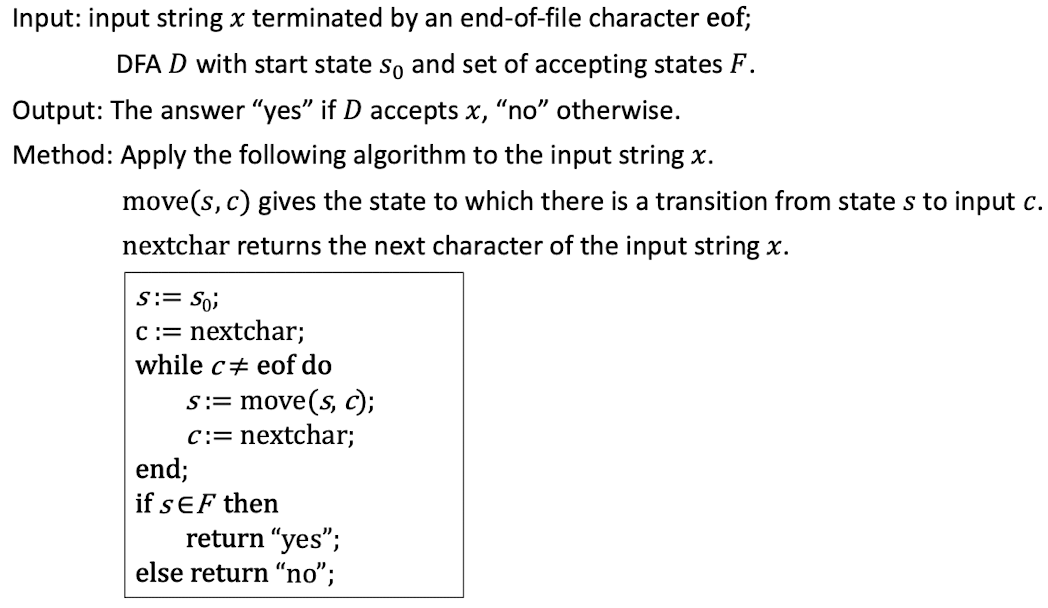

7.6 Algorithm: Simulating a DFA

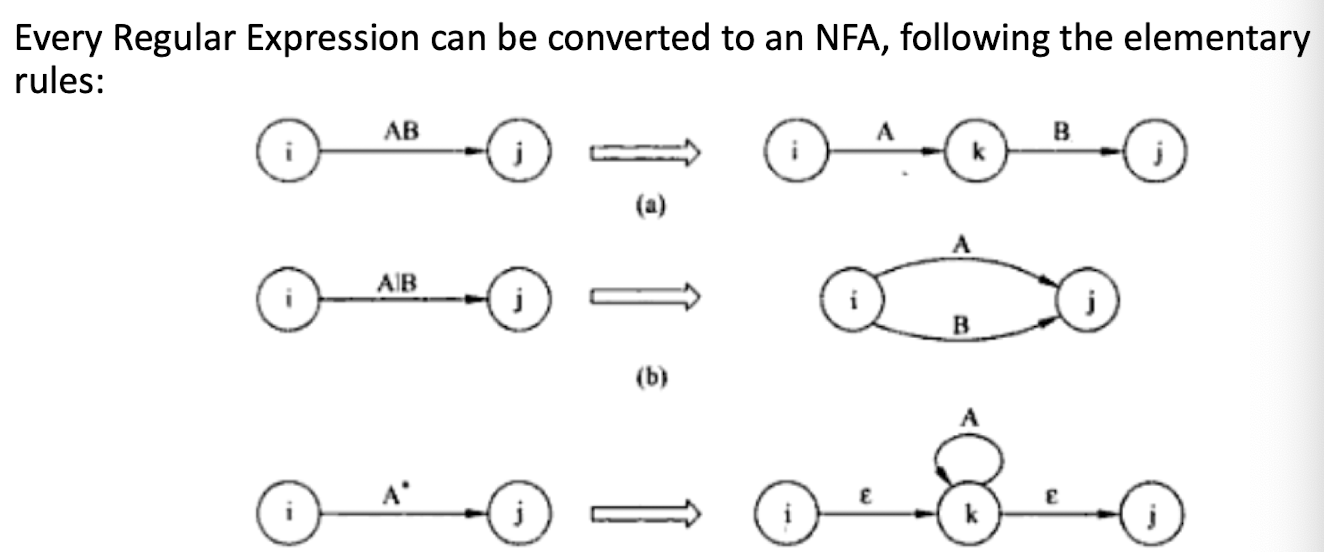

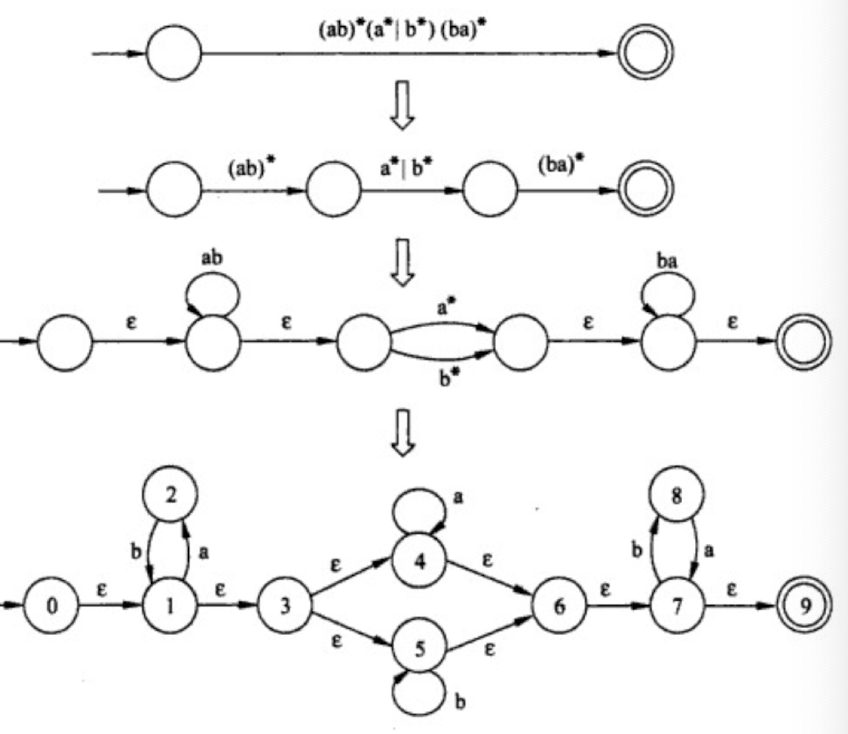

7.7 Regular Expression to NFA

[Break Regular Expression to NFA]

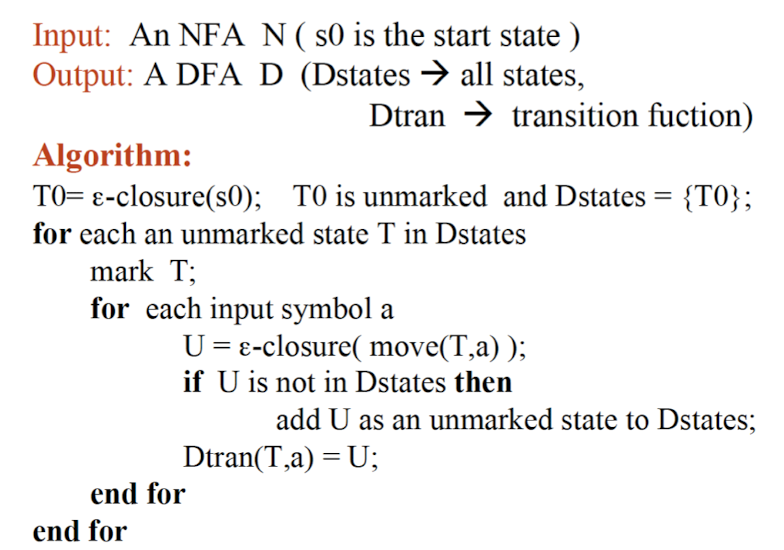

NFA to DFA

-

A DFA is a special case of NFA. The conversion of an NFA to a DFA needs to meet the two requirements on DFA:

- -closure(s): the set of all states reachable from on -transition (to meet the no ε-transition requirement of DFA).

- Regard all reachable states from one state on one input symbol as one state (to meet the one transition per input per state requirement of DFA).

-

Conversion Algorithm

- States of DFA obtained from NFA

- An NFA may be in many states at any time.

- If there are states, the NFA must be in some subset of those states.

- Given a set of elements, it has $2^N$ subsets.

- The DFA can have at the most $2^N$ states, where is the number of states of the NFA.

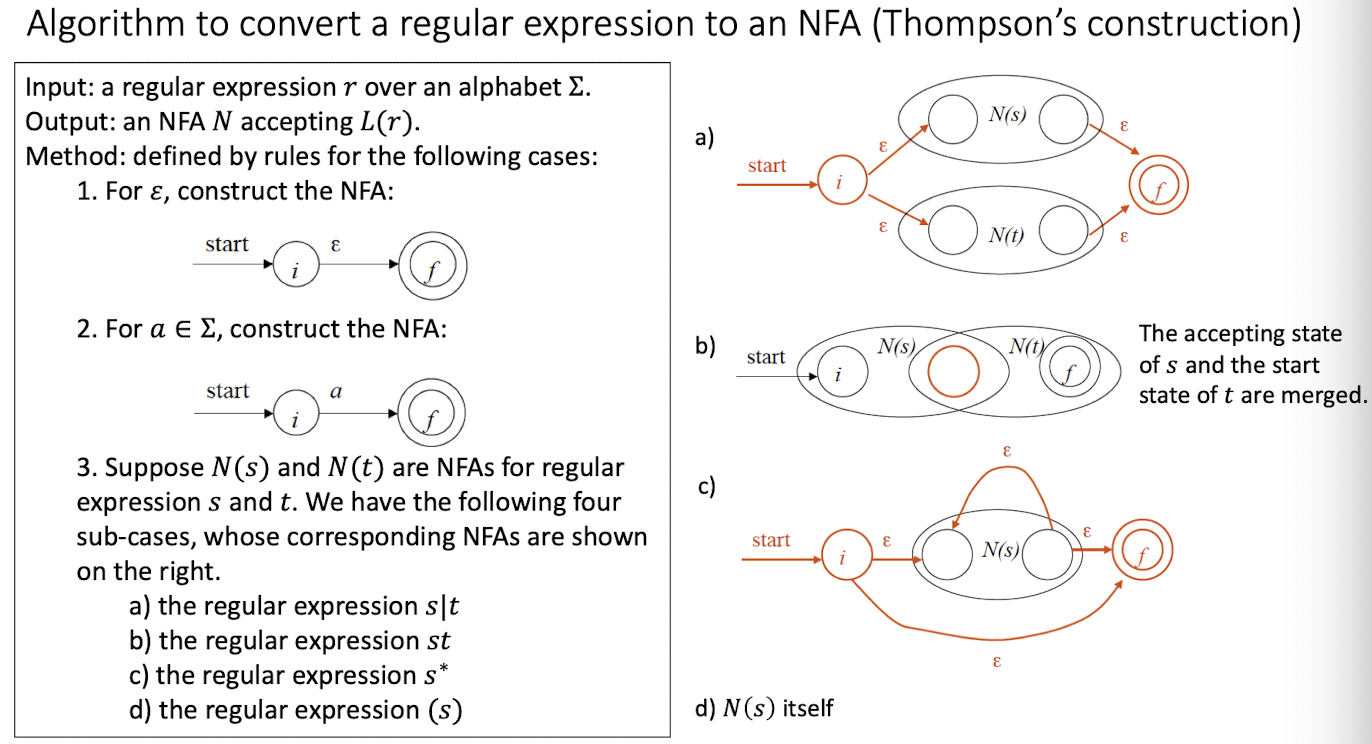

7.8 Regular Expression to NFA

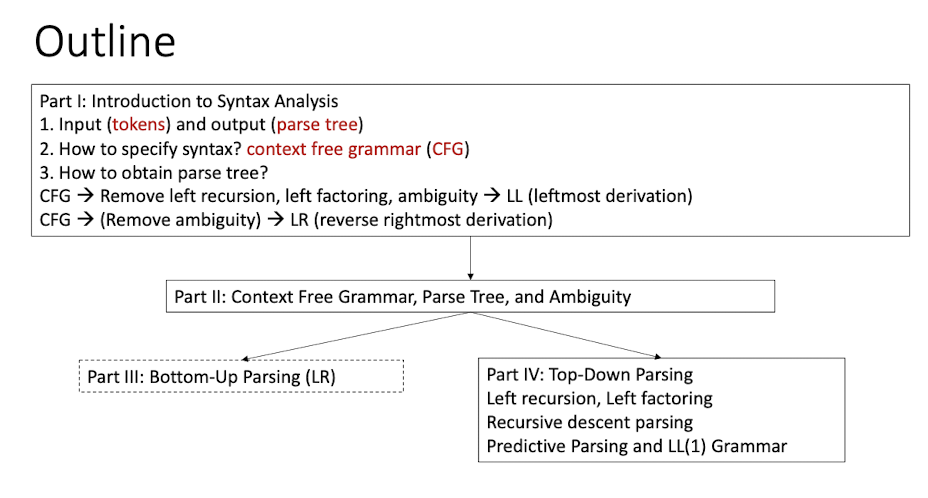

8 Syntax Analysis

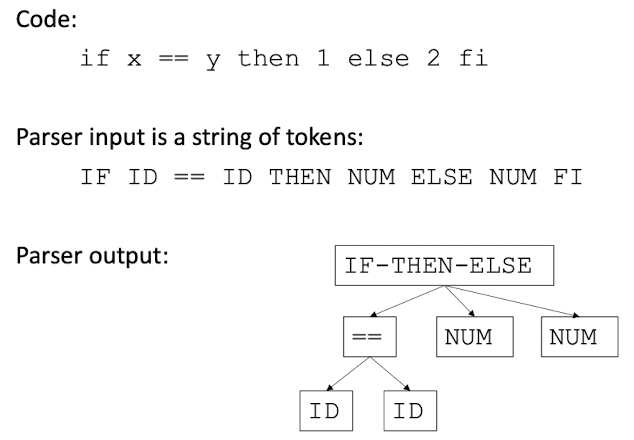

8.1 Introduction

- Input: sequence of tokens from lexical analysiss

- Output: a parse tree (syntax tree) based on the gsrammar of a programming language.

[Comparison between Lexical and Syntax]

[Example]

Syntax and Grammar

- In Pascal, program à blocks; block à statements; …

|

|

- The syntax of programming language constructs can be described by context-free grammar (CFG).

8.2 Context-Free Grammar

- $ G= (N,T,S,P)$

- $N$ is a finite set of nonterminal symbols (simplified as “nonterminals”);

- $T$ is a finite set of terminal symbols (simplified as “terminals”);

- $S$ is the unique start nonterminal($S\in N$);

- $P$ is a finite set of productions. Every production in $P$ is of the form $A \to \beta$, where $A \in N$ and $\beta \in (N \cup T)^*$.

- e.g., $N = {S}$, $T = {a,b}$, $S,P = {S \to aSb|ab}$, where $S \to aSb|ab$ denotes the language $L = {a^nb^n|n \geq 0}$.

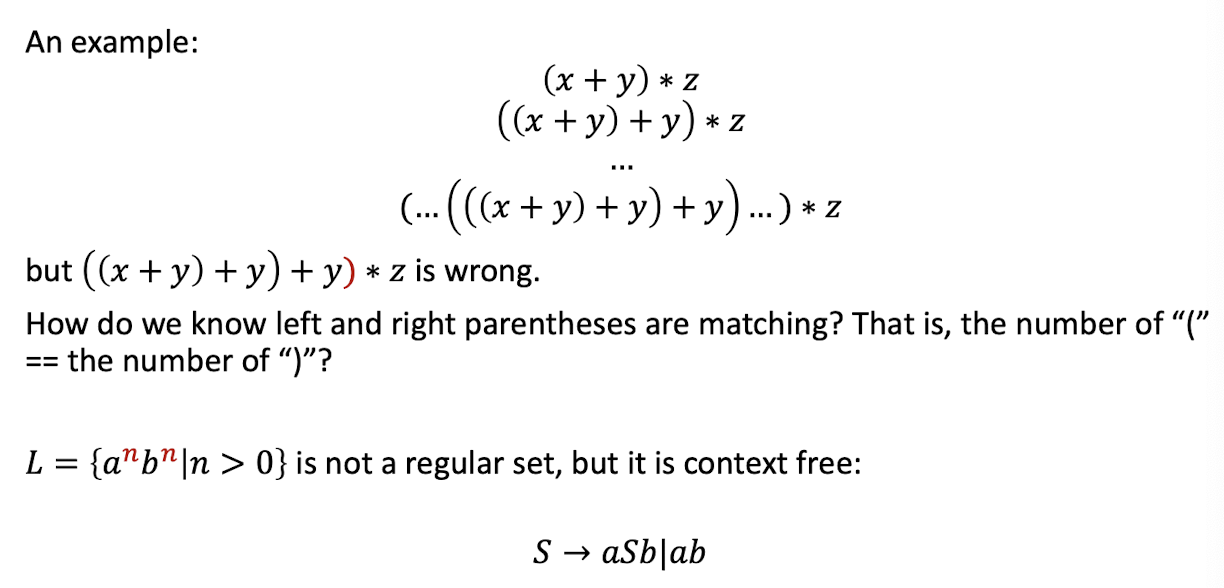

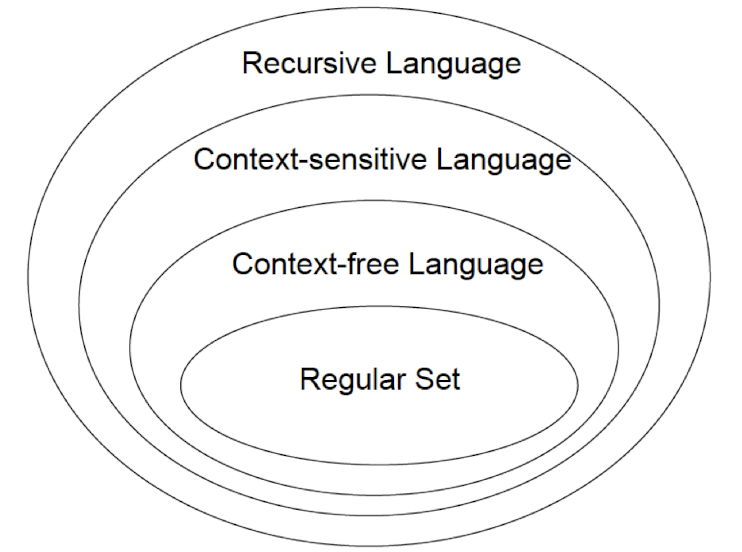

Not Regular Expression

Regular Expression, CFG, and Automata

Language Classfication

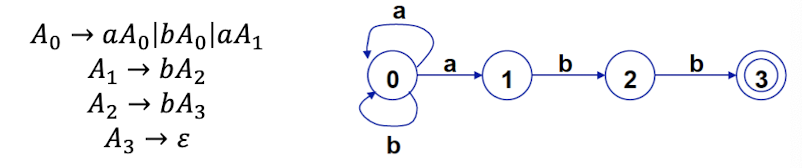

Regular Expression vs. CFG

- Every language that can be described by a regular expression can also be described by a CFG

- e.g., $(a|b)^*abb$

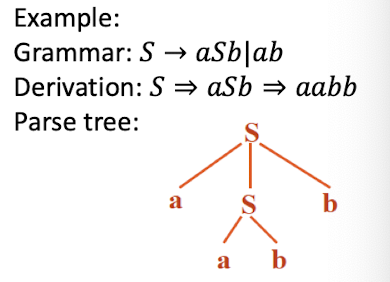

Derivations, Language of a CFG

- Based on a grammar for a language, we can generate sentences (strings consisting only of terminals) of the language. This is done by derivations. For CFG, derivation means start from the start nonterminal, repeatedly use productions to replace nonterminals, until a sentence is produced (i.e. all nonterminals are replaced).

- Grammar: $S \to aSb|ab$

- Derivation: $S \Rightarrow aSb \Rightarrow aaSbb \Rightarrow aabbb$

- where $\Rightarrow$ means “derives in one step”

- A CFG language is the set of all the sentences that can be derived from the start symbol of the CFG grammar.

- The reverse is syntax analysis (parsing): given an input string of terminals, is there a derivation for the string based on the grammar (is the string a sentence of the grammar)?

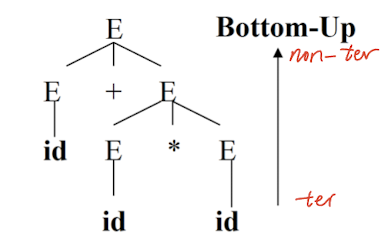

Parse Tree, Leftmost/Rightmost Derivation

- For CFG, a parse tree is a tree with the following properties

- The root is labeled by the start nonterminal;

- Each leaf node is labeled by a terminal or by ;

- An interior node is labeled by a nonterminal;

- If A is the nonterminal labeling some interior node, and $X_1X_2…X_n$ are the labels of the children of that node from left to right, then $A \to X_1X_2…X_n$ is a production.

- A string of terminals is a sentence of a CFG grammar iff there is a (can have more) parse tree for this string. The derivation of the sentence can be shown pictorially by this parse tree.

- Suppose the parse tree of the sentence is found.

- Leftmost derivation: only the leftmost nonterminal is replaced at each derivation step.

- E.g., grammar: $E \to E+E|E*E|(E)|id$

- Leftmost derivation: $E \Rightarrow -E \Rightarrow -(E+E) \Rightarrow -(id+E) \Rightarrow -(id+id)$

- Similarly, for rightmost derivation, the rightmost nonterminal is replaced at each step.

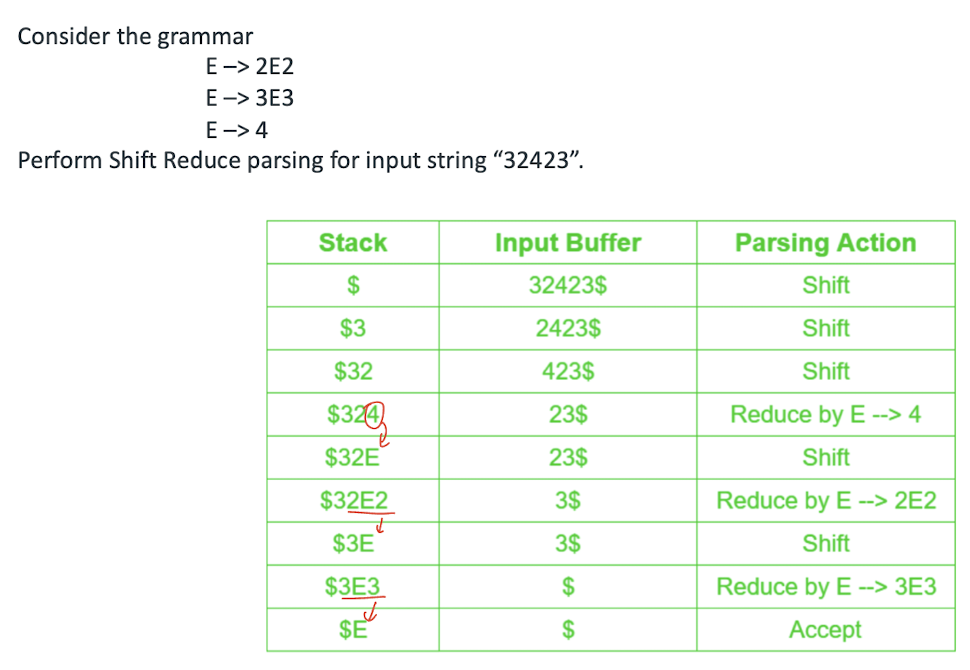

8.3 Parsing Methods

8.3.1 Bottom-Up Parsing

- Start at the leaves and build the parse tree from bottom up.

- Basic method: shift-reduce

- Shift symbols onto the stack;

- Reduce when handle is identified by left side.

- Used to implement automatic parser generator such as Yacc.

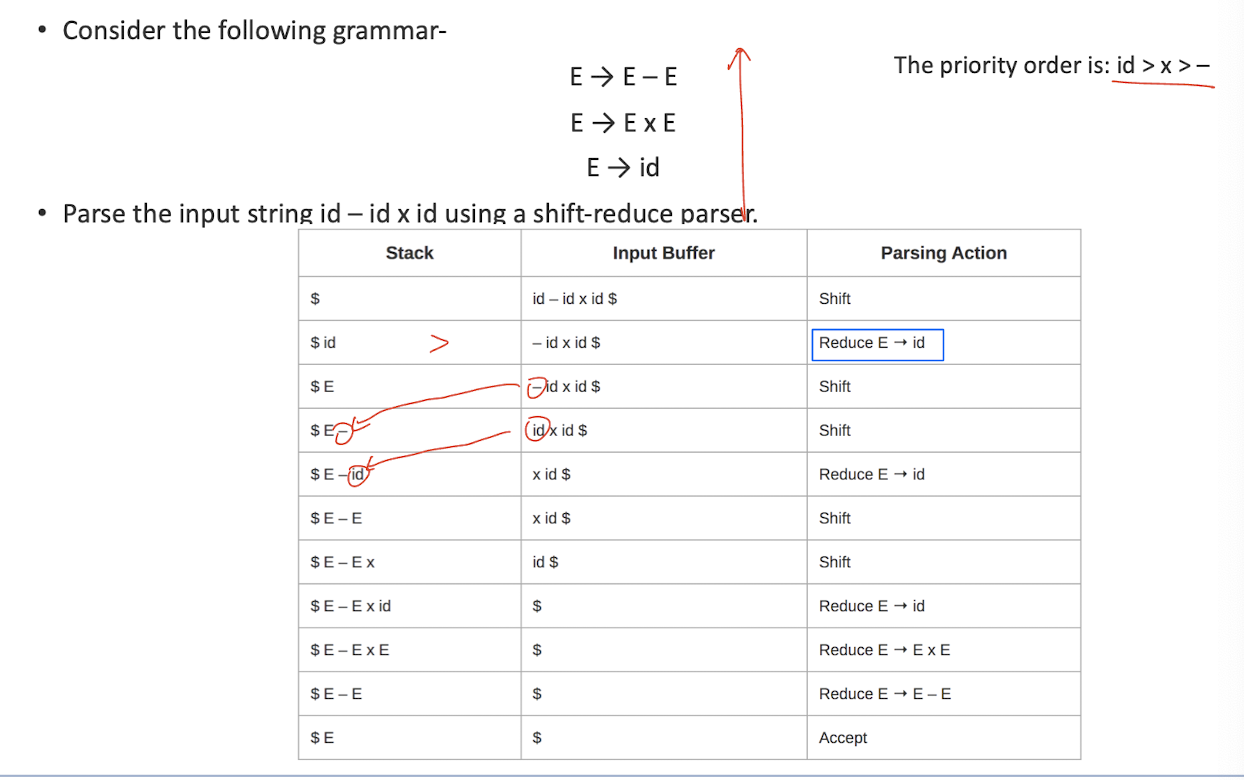

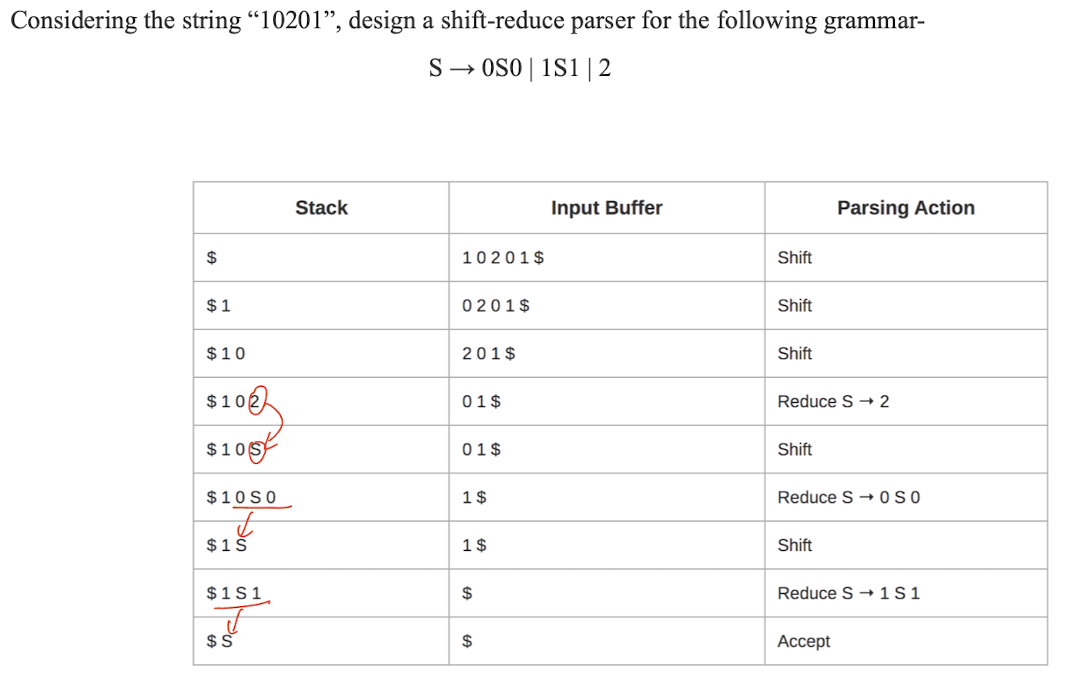

Shift-reduce Parser

- Two data structures:

- A Stack to hold the grammar symbols;

- An Input buffer to hold the string to be parsed;

- Stack contains only

$symbol; - Input buffer contains input string followed by

$symbol.

- Possible actions:

- Shift: move the next input symbol to the top of the stack;

- Reduce: replace the top of the stack with the appropriate non-terminal symbol ;

- Accept: parser reports the successsful completion of parsing;

- Error: parser is confused and is not able to make any decision. It can neither perform shift action nor reduce action nor accept action.

Important rules: If the priority of incoming operator is more than the priority of in stack operator, then shift action is performed. If the priority of in stack operator is same or less than the priority of in stack operator, then reduce action is performed.

8.3.2 Top-Down Parsing

- Start at the root of the parse tree and try to get to leaves. Can be efficiently written by hand.

- Only work for certain class of grammars:

- Unambiguous

- No left recursion

- No left factoring

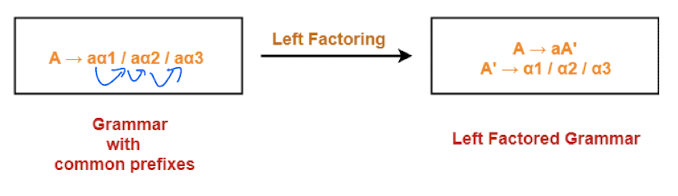

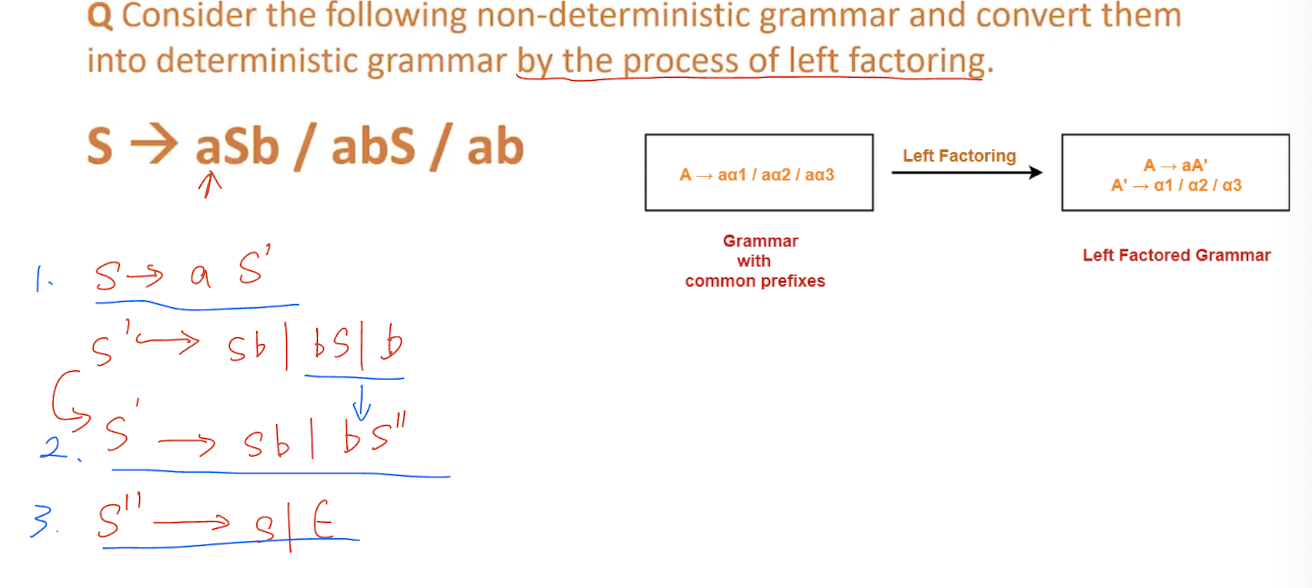

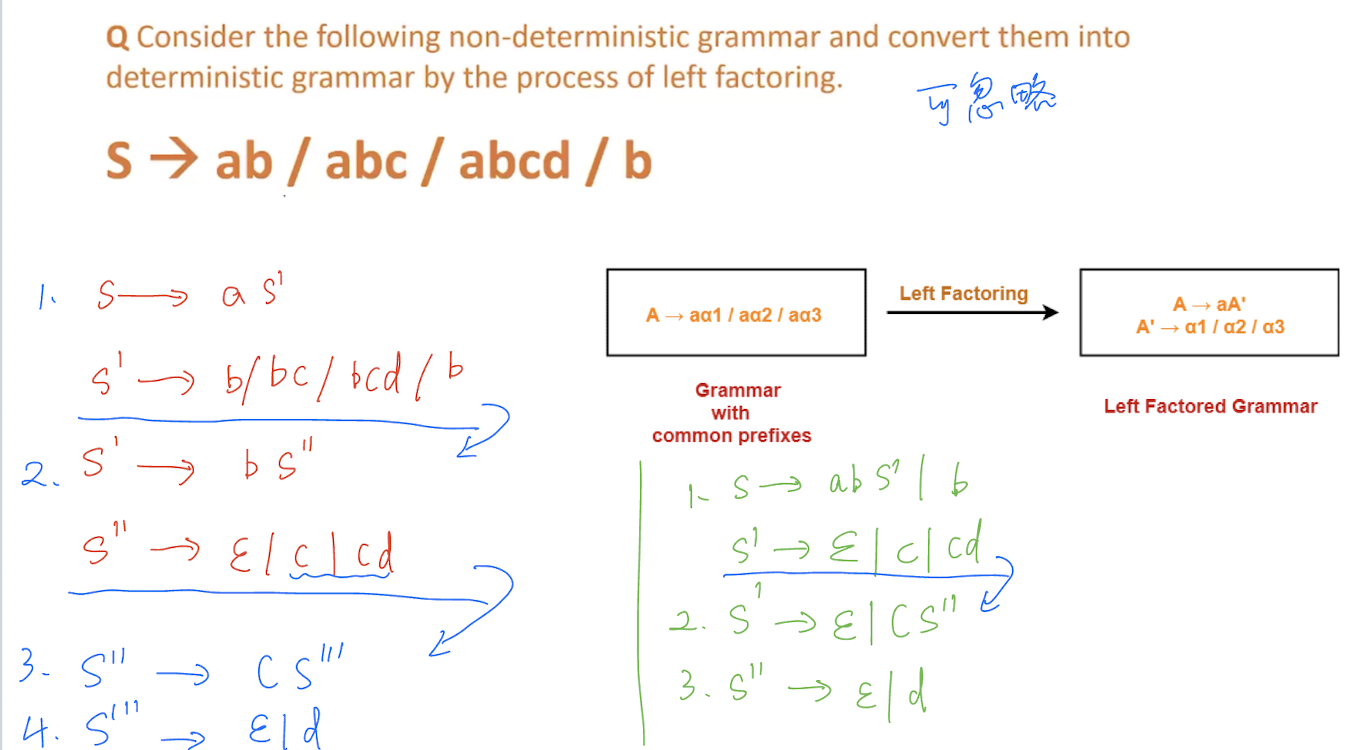

Left recursion: A grammar is left-recursive if and only if there exists a nonterminal symbol that can derive to a sentential form with itself as the leftmost symbol. That is, $A \Rightarrow^+ A\alpha$, where $\Rightarrow^+$ means the operation of making one or more substitutions, and is any sequence of terminal and nonterminal symbols. Left factoring: A grammar is left factoring if and only if there exists a nonterminal symbol $A$ that $A$ has $\alpha \beta_1 |\alpha \beta_2 $, where $\alpha, \beta$ are any sequence of terminal and nonterminal symbols, with $\alpha \neq e$ .

Recursive Production

- Recursive Production: if the same non-terminal at both left and right hand side of production

$$ S \to aSb, S \to aS, S \to Sa $$

- Recursive Grammar:if at least one recursive production is present

$$ S \to aS | a, S \to Sa|as, S \to aSb|ab $$

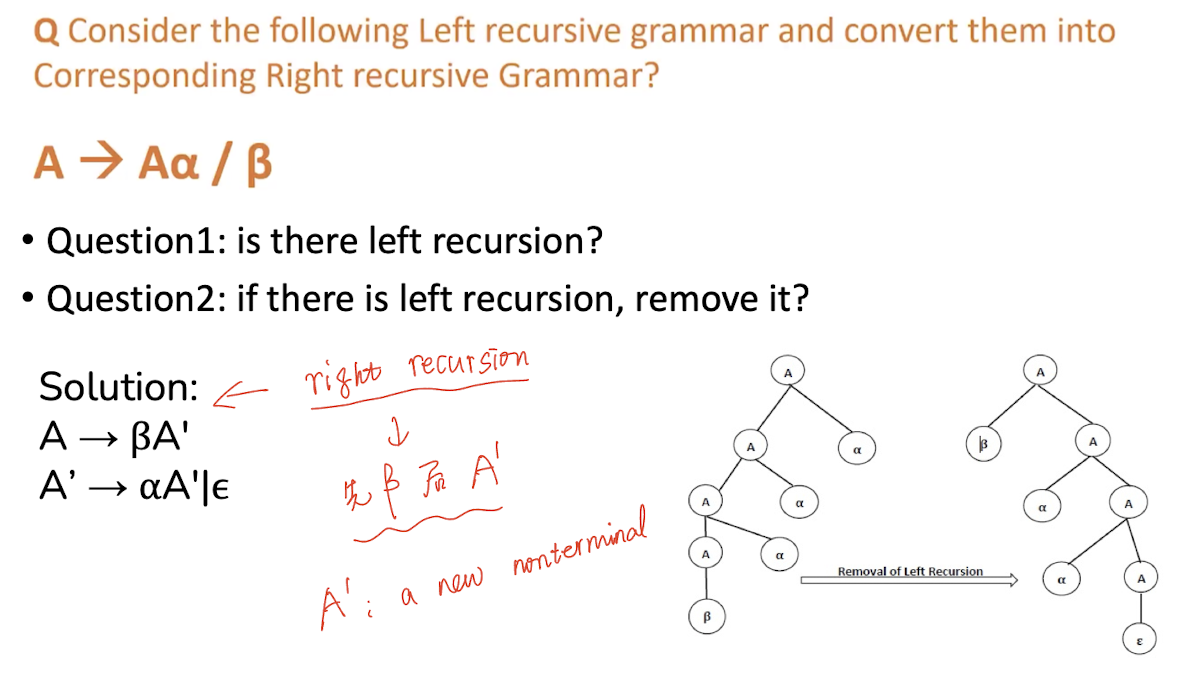

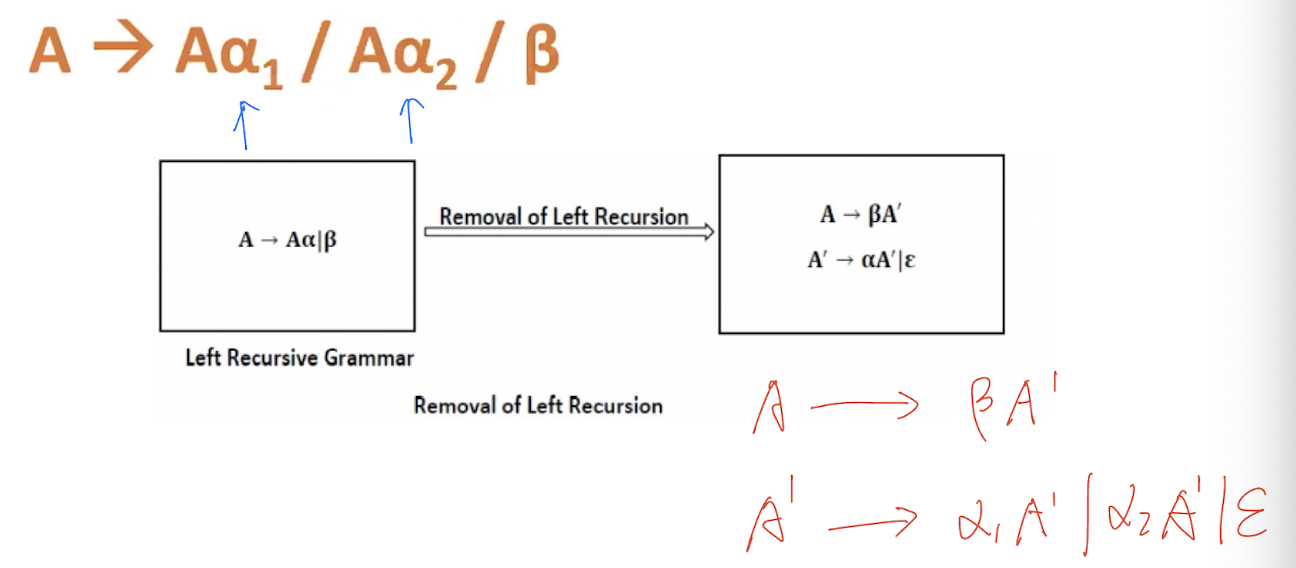

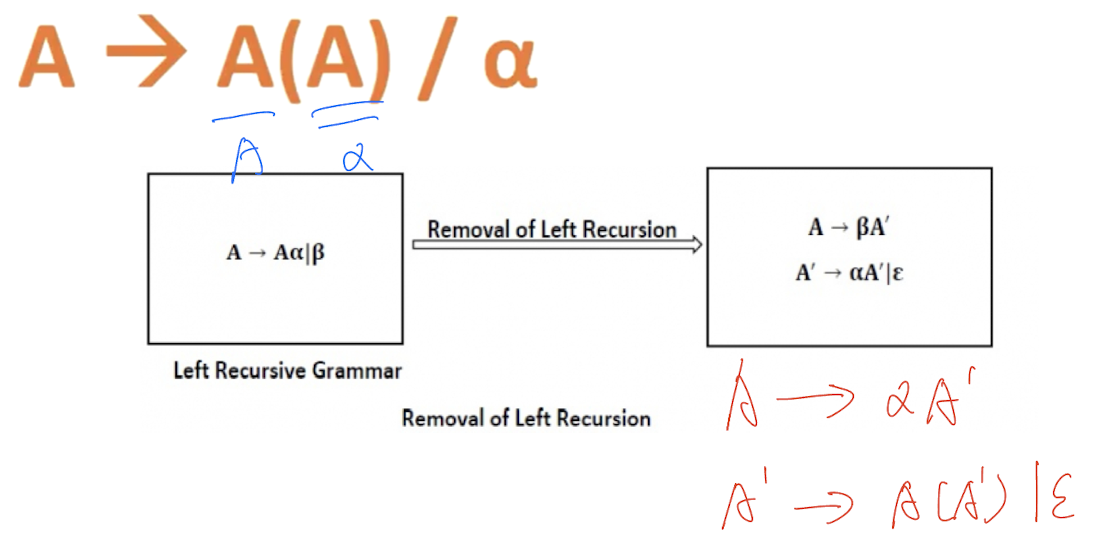

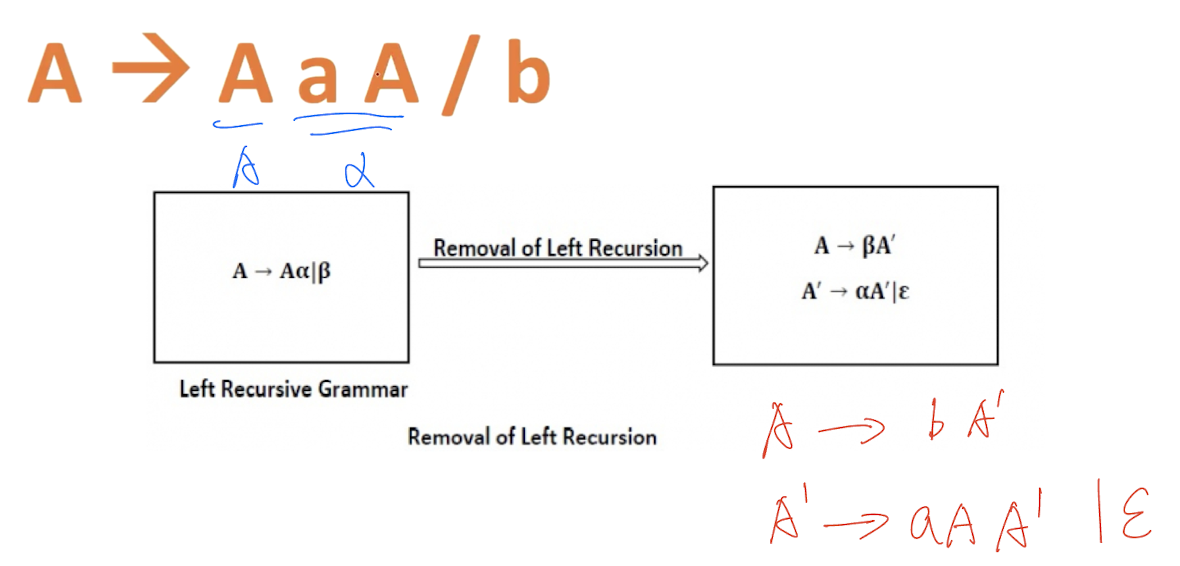

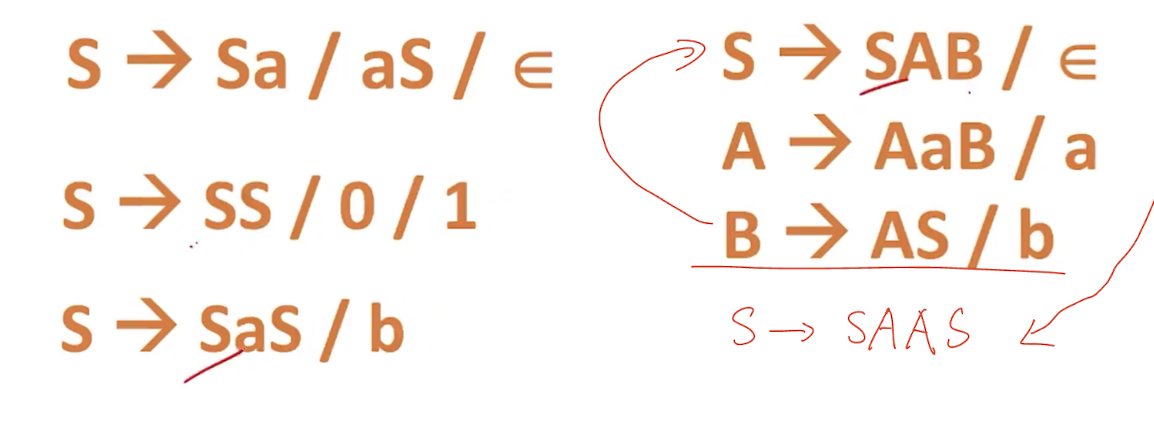

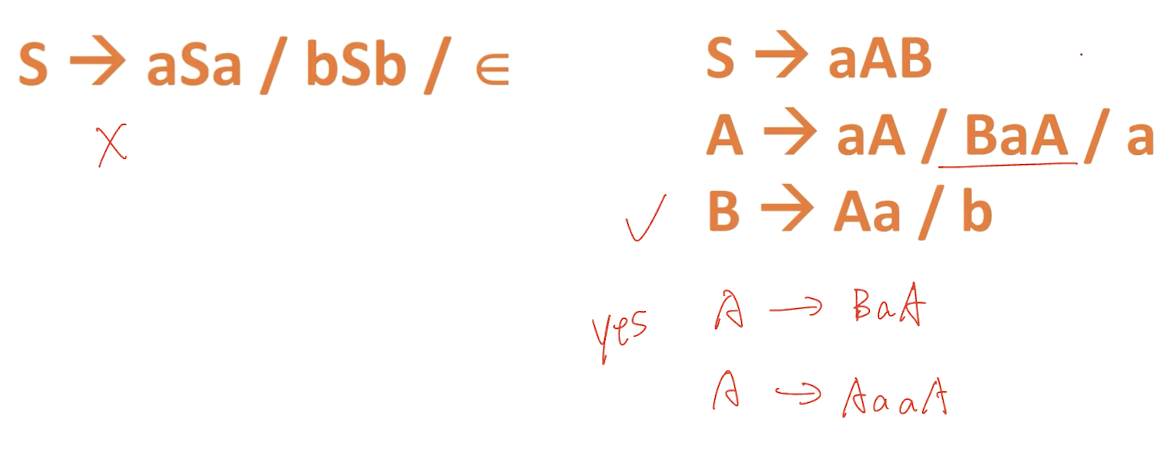

8.3.3 Convert Left recursion into Right recursion

- If a CFG contains left recursion then the compiler may go to infinity loop, hence, to avoid the looping of the compiler, we need to convert the left recursive grammar into its equivalent right recursive production

[Examples]

Ambiguous Grammars

- Each parse tree has a unique leftmost/rightmost derivation.

- Sometimes a grammar may have (produce, imply) more than one parse tree for some of its sentences. Such a grammar is said to be ambiguous. For such a sentence (i.e., having more than one parse tree), its leftmost and rightmost derivations may be different.

- e.g., grammar: $E\to E+E|E*E|id$, sntence

id+id*id

- e.g., grammar: $E\to E+E|E*E|id$, sntence

- Grammar which is both left and right recursive is always ambiguous but ambiguous grammar need not be both left and right recursive

[Example]

8.3.4 Non-deteministic Grammar

- The grammar with common prefix is known as non-deterministic grammar.

- $A\to \alpha\beta_1, \alpha\beta_2$

- Grammar with common prefixes requires a lot of Back-tracking, which is time consuming and inefficient.

- To avoid the back-tracking, we need to remove the common prefix from the grammar, like convert non-deterministic grammar into deterministic grammar.

Normalization of CFG

- Chomsky Normal Form (CNF), if every production is in form: $A\to BC|a$

8.4 First and Follow Sets

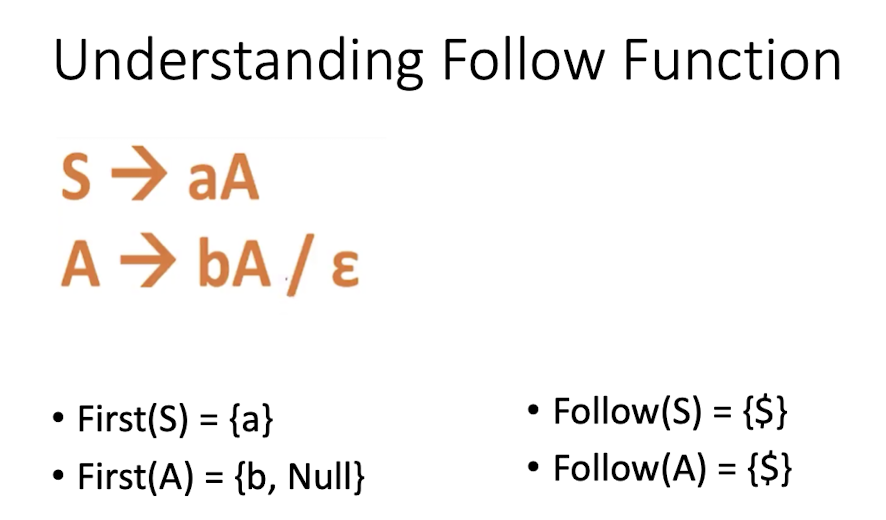

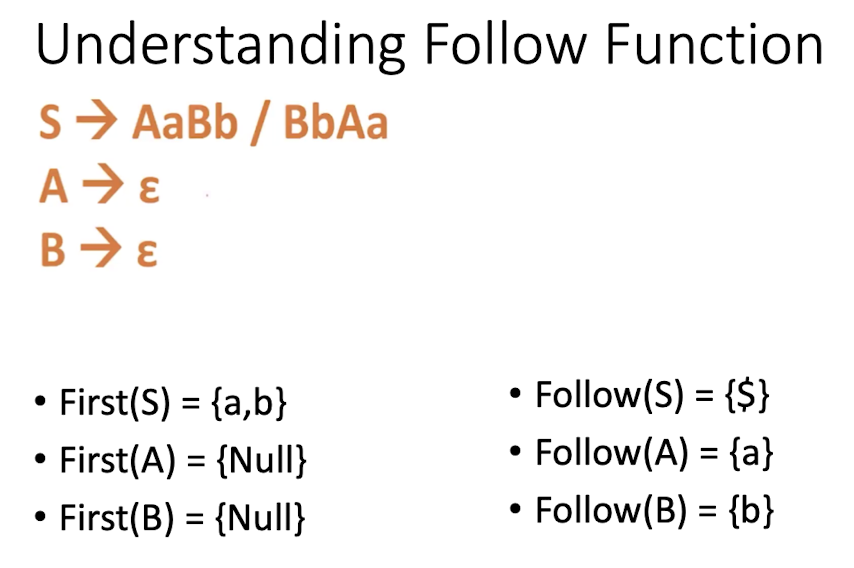

First

- First(S) is the set of all terminals that may begin the strings in the language generated by S.

[Examples]

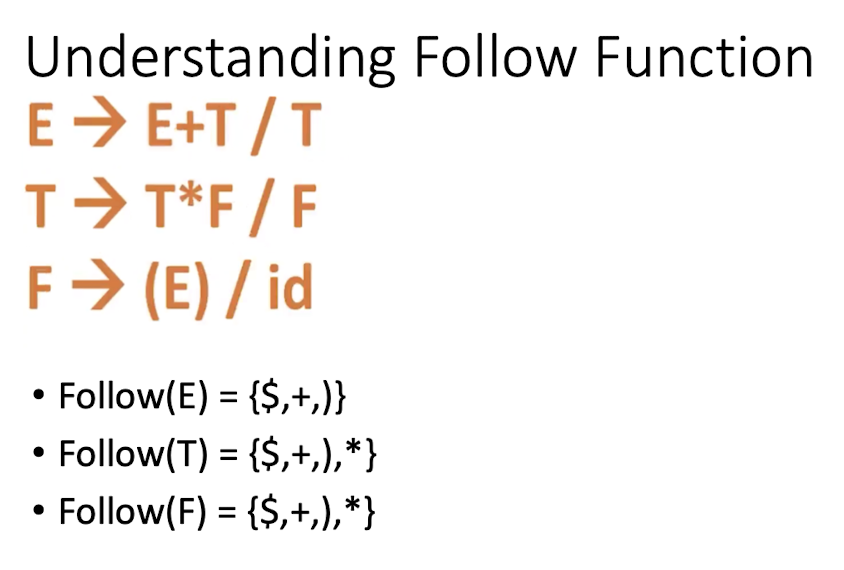

Follow

- Follow(A) is the set of all terminals that may follow to the right of (A) in any form of sentential Grammar.

- Rules:

- if A is the start symbol then Follow(A) = {$}

- if $A \to \alpha A B, B \to \varepsilon$, Follow(A) = First(B)

- if $S \to \alpha A$ Follow(A) = Follow(S)

- $S \to \alpha A \beta$, where $\beta \to \varepsilon$, Follow(A) = First(B) U Follow(S) - {$\varepsilon$}

[Examples]

学习笔记,仅供参考